Women’s health has long been underfunded. Women deserve better

[ad_1]

Propped on my desk is a cherished photo, taken after my daughter was born in 2018. I’m sitting next to my mother and grandmother with my newborn swaddled in my arms. We’re wearing matching headbands and beaming with happiness. I was too sleep deprived at the time to fully appreciate the scene, but five years later, I know I’m lucky to have captured that moment: four generations of females in my family enjoying each other, featuring our new baby girl.

My mother, who organized the photograph, knew that time was special and fleeting. When the photo was taken, my then 87-year-old grandmother lived in her own apartment. But a year later, she fell and broke her hip, and before she could recover, the pandemic started. A broken hip followed by extreme social isolation drastically affected her mobility, strength, and cognitive function. Her mind and body deteriorated quickly, and she will likely spend the rest of her life in an assisted living facility.

My grandmother’s life story is unique, and yet, in these later years, her experiences are all too similar to so many other older women.

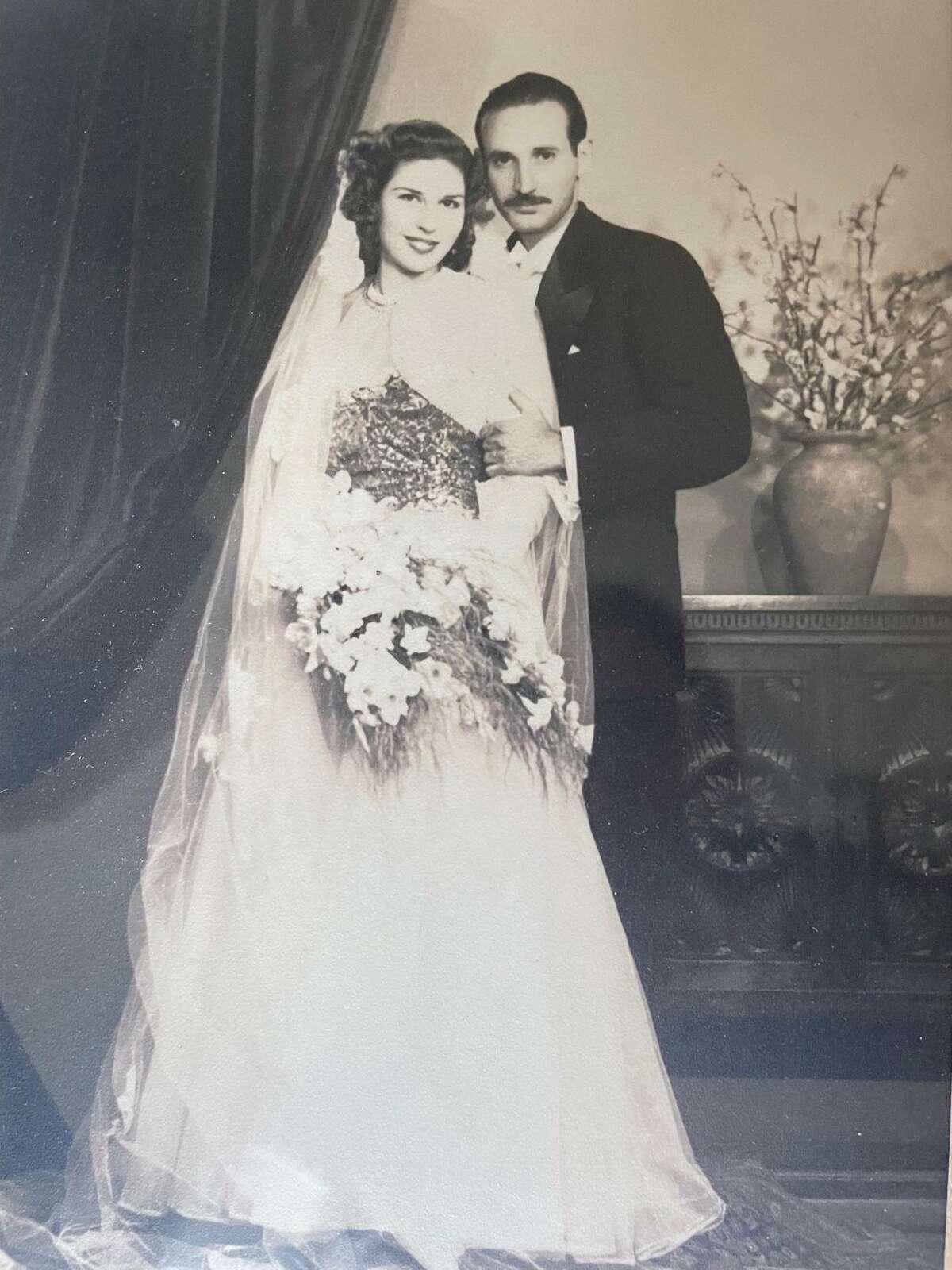

She was born in Egypt in 1930, the eldest of five siblings. In her 20s, she fell in love with my grandfather, a naval officer, and they married in 1952. My grandparents each had movie-star good looks, and together they must have turned heads wherever they went. The young couple spent their early married life in Port Said and Suez, my grandfather piloting ships through the Suez Canal and my grandmother commuting between Suez and Cairo to earn a degree in translation. They had two daughters. When the canal shut down due to geopolitical conflict, the family moved to Nigeria, where my grandfather continued piloting ships and my grandmother taught French at an elementary school. Years later, they sent my mother to college in the U.S. and eventually followed her there. First, to Chicago where my parents met and married; then, to Northern California where my parents decided to raise me and my twin brother.

Deena Emera’s grandparents were married in 1952.

Provided by Deena EmeraUnexpectedly, my grandfather died soon after their move to California, when my grandmother was in her early 50s. My recollection of that period is hazy — I was 5 at the time — but I clearly remember the next stage of my grandmother’s life. My brother and I slept over at her house regularly, her chocolate Weimaraner dog zipping around the house, her African gray parrots mimicking the trilling and beeping noises of the phone and fax machine. My grandmother loved animals and she loved to work. She was an agent at the Mutual of Omaha, a billing specialist at UCSF, and a saleswoman at Sears. Etched in my memory is bounding up the Sears escalator to find her talking about carpets with customers whom she adored. She would have continued working forever if she could have, joking with her customers while helping them find what they need. Through all the uncertainty and upheaval in my grandmother’s life, she worked hard and enjoyed life.

I have mixed emotions about my grandmother’s current situation. I am grateful to the caregivers who tend to her needs, but I’m also angry when I see her being neglected. There are too few caregivers to provide the care that each person deserves. According to a mid-year 2023 report by the American Health Care Association, over 75% of nursing homes are facing moderate to high levels of staffing shortages. As people are living longer lives but not necessarily healthier ones, I know my family isn’t the only one facing this challenge. How do others manage the care of their aging relatives? As a society, why haven’t we demanded to have this conversation and come up with better solutions? Since women are often caregivers and we tend to live longer, this conversation is especially critical for us. Don’t the women in our communities — our grandmothers, mothers, and ourselves — deserve better?

I am also frustrated by the lack of education and understanding of the science. As a biologist who studies the aging of the female reproductive system, I’ve learned about the negative effects of a long history of male bias in biomedicine, chronically low budgets for studies on women’s bodies, and taboos around periods and menopause. Women have been misdiagnosed and their symptoms dismissed for decades. Menopause marks the end of reproductive cycling but it also marks the beginning of serious health problems, including stroke, heart disease, dementia, and osteoporosis. We know surprisingly little about this transition experienced by half the population. My grandmother had a stroke and suffers from dementia, osteoporosis, and arthritis, so I can’t help but wonder: if we knew more and were better at educating women about their bodies, would the quality of her later life have been better?

Over the last five years, the conversation about women’s bodies has been changing. Taboos are being broken, as celebrities like Oprah are sharing their experiences openly. There has been a surge of investment in research on women’s biology. For example, since 2018, the National Institute of Health has doubled funding for reproductive longevity. But given just 1% of biopharma investment goes to female-specific conditions beyond cancer, we have a long way to go.

In the meantime, we’re doing our best to give my grandmother what she needs at this stage of her life — companionship, love, and vigilant oversight of her care. As I sit with my grandmother in her room, gazing at the photo of the four of us that my mom taped to her wall to remind my grandmother of her amazing life and legacy, I hope our daughters and theirs will have a healthier and more empowered future.

Deena Emera is an evolutionary biologist at the Center for Reproductive Longevity and Equality at the Buck Institute. She is the author of “A Brief History of the Female Body: An Evolutionary Look at How and Why the Female Form Came to Be.”

[ad_2]

Source link