What Myriam Gurba is Reading Now and Next ‹ Literary Hub

[ad_1]

Myriam Gurba, author, activist, and educator, is likely best known, now, for illustrating to thousands the racist realities of the publishing industry. American Dirt was the flashpoint that, largely because of Gurba’s consistent tweets and the eventual publication of her takedown review, helped #DignidadLiteraria go viral, over 140 authors sign an open letter to Oprah, and Flatiron cancel the AD book tour. Ultimately Gurba and other #DignidadLiteraria activists such as David Bowles and Roberto Lovato met with Macmillan highers up about doing more than promise to diversify their catalogs in the wake of the scandal. In short, this person is devoted to her politics and has the capacity to turn a tank.

That same energy is in Gurba’s writing. It has the intensity of making plain what you likely have felt or experienced, but not put language to. When I first read her memoir/novel Mean in 2017, I was amazed at how she managed to thread what feels like an impossible needle. Moving at a quick clip, the book attends to complex realities such as racism, queerness, intersectionality, sexual violence, and disordered eating. It does more than simply describe what Gurba had endured, but has powerful philosophical meditations on the social structures and thinking that made those struggles happen in the first place. Perhaps most unbelievable of all, it is funny as hell. I teach this book as often as I can and never regret it. (Here’s one of my favorite excerpts.)

Gurba’s new essay collection Creep operates similarly to Mean. In its starred review, Kirkus states, “Gurba’s lyrical prose forces us to face the sexism, racism, homophobia, and other systems of oppression that allow some Americans to get away with murder while the rest of us live in constant fear. Every piece is rife with well-timed humor and surprising conclusions, many of which come from the author’s staggering command of history.” Always hungry for Gurba’s insights and snappy writing, I couldn’t stop reading Creep. Personal experiences spin out into edifying and often hilarious history and language lessons. Gurba also has such specificity in her images that rub against hilarious and sad both at once, as in the description of a teacher: “Her orthopedic shoes made suffering-mammal sounds.” In 2019, Gurba did a few small essays for Paris Review in which she meditated on a word. In one that appears in Creep, “One Word: Striking,” she talks about her terrifying experiences of domestic violence, beauty, the OED, the Wife of Bath, with each link or leap done with precision.

When describing her life with a terrifying, violent, and controlling now-ex, Gurba pins down so much of why people remain stunned and confused at why she would stay (the answer: when people leave domestic violence situations is when they are most likely to be murdered—and this is something they can feel). “The implication is that people who studiously ask questions of people like me could never get stuck in a situation like mine, that people like me are stupid, masochistic, or insane,” she writes. Because she is great at lists and writing paragraphs with the energy of a manifesto, I’ll end with a quote about domestic violence and masculinity from the titular essay.

Every man who rapes, smacks, whips, trips, spits on, gouges, abducts, strangles, and otherwise degrades, dehumanizes, and destroys women is kin to someone. Every badly behaved man is a father or a brother or a son or an uncle or a cousin or a brother-in-law or a godfather or a stepfather or a grandfather or a great-grandfather or a friend or a best friend or a prom date or a next-door neighbor or a favorite teacher. Embedded within these systems of family, friendship, and community, these creepy men may appear harmless, their evil obscured by a benign collective presence, a fog of sorts. This softness swaddles and protect them. This fog abets.

Do you dwell in the fog? Would you admit it if you did?

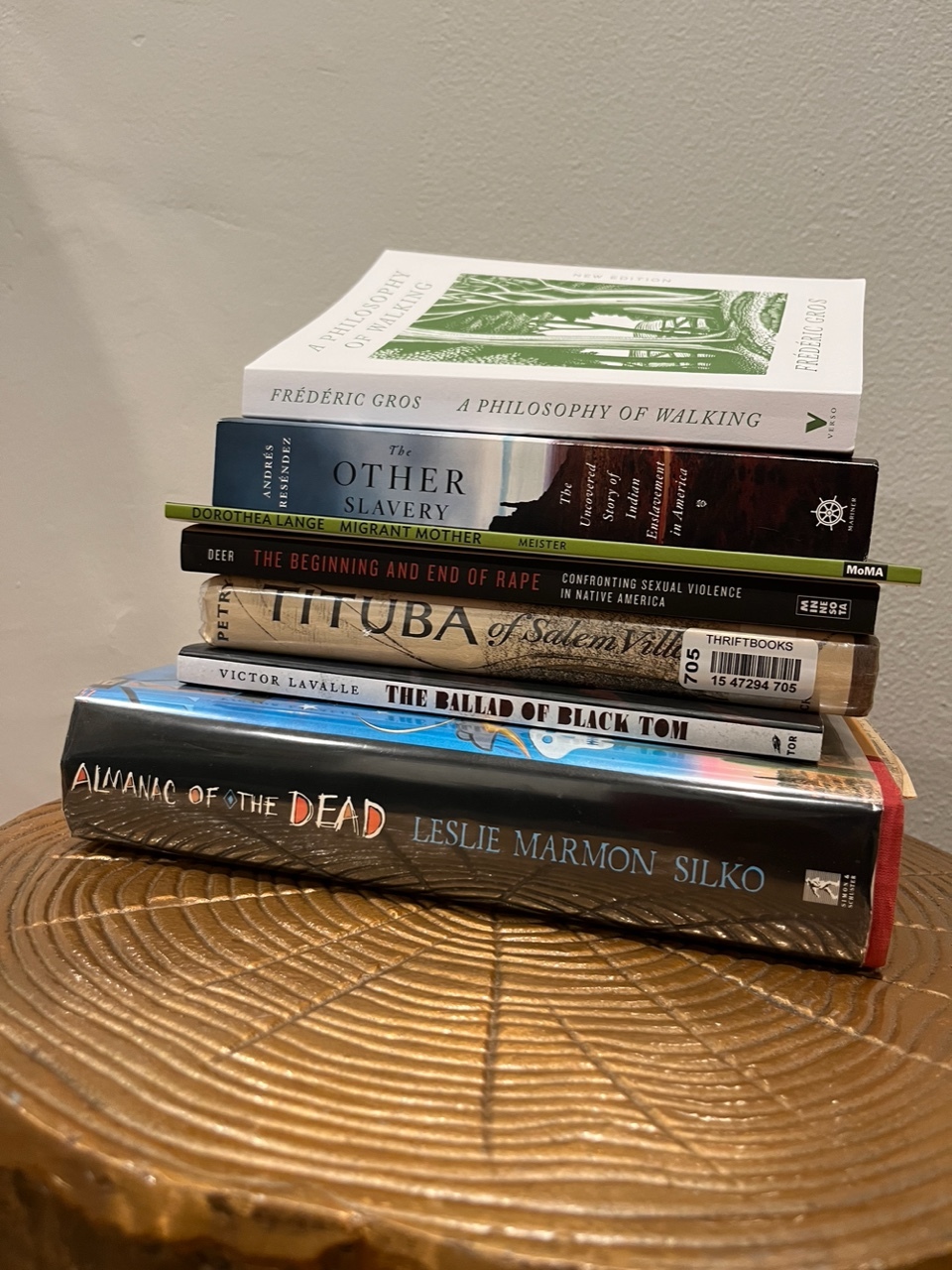

Gurba’s note about her to-read pile makes me hope for some breadcrumbs on what she’s writing next. She explains, “Some of the books, like Victor LaValle’s and Frederic Gros’s, are for pleasure. Some, like the ones on Lange and Tituba are for research.”

*

Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking

In her New York Times review of this book in 2014, Lauren Elkin writes, “In chapters on Nietzsche, Rousseau, Rimbaud, Thoreau and others, Gros considers the inspiration they each found in walking. Nietzsche even advised, aphoristically, ‘Do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement.’ Gros takes this to mean that books bear in their very DNA the circumstances of their conception; we can tell when they have been composed entirely at a desk, their authors hunched and squinting over a stack of books.”

Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America

Reséndez’s book was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2016. The judges’ citation reads, “The Other Slavery upends conventional historiography to show how slavery, more than epidemics, led to the catastrophic decline of Native populations in the Americas. Andrés Reséndez tracks slavers across centuries, digs for evidence in brutal gold and silver mines, and tells stories of real captives to personify a system that enslaved as many as 4.9 million. Neither abolition nor the 13th Amendment brought an end to the other slavery, hidden from much of our history until now.”

Sarah Harmanson Meister, Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother

This slim volume is by a MoMA curator interrogating what she calls “arguably the most famous photograph ever made” of Florence Owens Thompson near a camp for people who were impoverished migrant manual laborers during the Great Depression. Meister writes in an essay about the book (which I recommend perusing if only to see a 1979 photograph of Thompson with three of her daughters over 40 years after Lange’s), “I am just one of many interested in unraveling the mysteries of this photograph and our varied responses to it. It was decades before the public learned that Thompson was Cherokee: we now grapple with how its reception would have differed if that had been known.”

Sarah Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America

Deer, a 2014 recipient of the MacArthur “Genius” Grant, is an activist and legal academic who has spent decades on rape victim advocacy. The stunning numbers of Indigenous women who endure or succumb to sexual violence in the United States is undeniable. Indigenous women are 2.5 times higher than women of any other race to experience sexual violence—with 86% of the men exacting this violence being non-Indigenous. Of course, this is just what is recorded—the numbers of those who experience sexual assault are likely higher. Charon Asetoyer, the Executive Director of Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center, says of the book, “The Beginning and End of Rape documents the brutal history and contemporary reality of how rape has been used and continues to be used against Native women by the federal government to create a cultural implosion of destruction for generations. Rape, burn, and pillage continues when Native American women do not have equal protection of the law extended to us.”

Ann Petry, Tituba of Salem Village

Petry cuts an impressive figure if only because she was the first Black American woman to sell more than a million copies of a novel (The Street in 1946). Tituba of Salem Village is a children’s novel published about 20 years later that considers the historical figure of Tituba—an enslaved woman who was perhaps from Barbados, perhaps Indigenous (perhaps both), likely named after her tribe or her hometown. In short: little about her actual life and experience exists in a written record, though there is plenty of conjecture. But she was one of the first people charged with witchcraft in 1692. What was news to me is that she was able to testify against the accusations as enslaved people were legally able to give testimony in court. Despite her forced confession, Tituba wasn’t killed for witchcraft. She did remain enslaved, was imprisoned, and ultimately sold. The archive doesn’t provide anything beyond that. Several writers have found Tituba a compelling figure in the drama of the Salem Witch Trials, including Arthur Miller, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, and Maryse Condé.

Victor LaValle, The Ballad of Black Tom

I’m always down to see someone come for H.P. Lovecraft, and LaValle has done just that with this sharp novella. The Ballad of Black Tom retells Lovecraft’s racist short story “The Horror at Red Hook.” In a review for Slate, Tammy Oler writes, “The Ballad of Black Tom couldn’t be timelier, for Lovecraft’s influence on pop culture is more powerful than ever, even as criticisms of his racism and xenophobia have swept through literary and fan circles…[The novella] is thrilling in part because LaValle uses them instead as his starting point, re-imagining Lovecraft’s universe through the eyes of a black man.” Oler goes on to state, “Lovecraft pulled back the veil to show us his racist monsters; LaValle pulls back the veil to show us how the monster of racism dooms us all.”

Leslie Marmon Silko, Almanac of the Dead

Lou Cornum wrote about Almanac of the Dead during its thirtieth year of publication here at Lit Hub. They write, “In its epic-scale narrative of a post-1492 planet, Almanac illuminates some of the reasons the bronze body of Columbus has repeatedly bitten the dust alongside Confederate monuments, almost 60 of which have also been removed, relocated, or renamed in the last year. While Silko has said her first novel Ceremony, written in 1997, explored the connective tissue between the United States and Asia, namely war and nuclear harm, Almanac turns to the entanglements of Africa and the Americas nowhere more obvious than in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The book insists through the unofficial histories voiced by its characters, who exist in the peripheries of dominant society, that the continual violence of life across and in the borderlands has its origins in European conquest stretching back hundreds of years but surely not destined to continue forever.”

[ad_2]

Source link