The Real Costs Of Launching A Black-Owned Beauty Business

[ad_1]

Brianna Arps has always loved how fragrance made her feel.

A spritz of perfume post-shower was the ultimate form of self-care to her. “It helped me feel good about myself, despite all of the bad that was happening around me,” the brand marketing manager and former digital editor says. “It reminded me that I’m worthy of giving myself a fighting chance to survive.”

But Arps also noticed a lack of Black-owned brands in the fragrance industry, so in 2021, she launched MOODEAUX, a clean fragrance brand. “There was no one really that was telling our unique scent stories,” she says. “And how we connect with fragrance, and the impact that fragrance can have on your mood.”

Upon launching her brand, Arps joined a chorus of other Black women founders who realized that their needs were being overlooked by the beauty industry they’ve personally invested so much in.

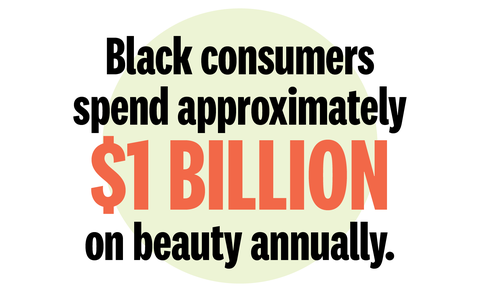

Black consumers spend approximately $1 billion on beauty annually, according to a Nielsen report from 2018. In 2017, they spent a total of $152 million on perfume and fragrance alone and more than $470 million on hair care.

But even as spending booms, Black people still aren’t always considered in the development of some of today’s most popular beauty products. “I didn’t see my face, my hair type, or my skin tone represented when I looked at makeup aisles,” Alicia Scott, founder of Range Beauty, says. “Something had to change.”

Scott previously worked as an account executive for an Australian fashion showroom. She’d often help out backstage during fashion events, and after noticing the lack of makeup shades available to darker-skinned models, she launched Range Beauty in 2017. The cosmetics brand features mostly brown to deep brown foundation shades for people with acne and eczema—both conditions that affect Black people at a higher rate compared to other groups.

While some beauty companies have tried to diversify their lineups, there’s still a long way to go—and Black entrepreneurs like Arps and Scott are stepping in to create brands with their own needs and experiences in mind.

But starting a business isn’t cheap, and the price of being a Black beauty founder is steep in more ways than one.

Eye-watering startup costs prevent many Black founders from even getting off the ground.

The average cost of starting a small business is around $40,000 in the first year, according to research conducted by Shopify in 2021.

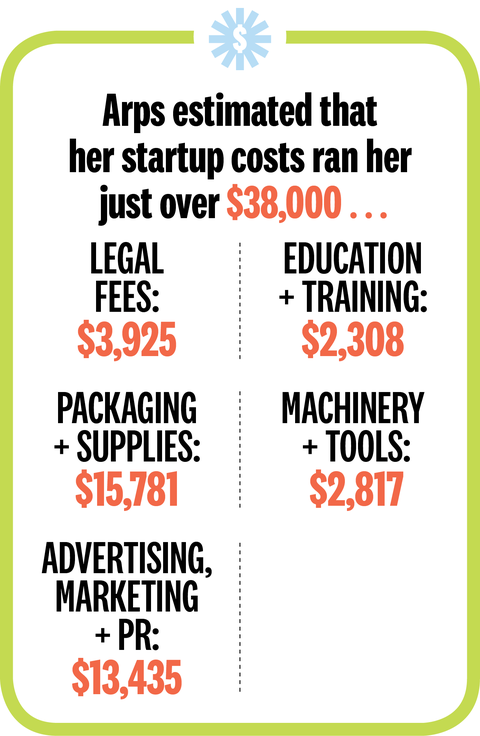

From 2018 to her launch in 2021, Arps estimated that her startup costs ran her just over $38,000 split between legal fees ($3,925), packaging and supplies ($15,781), advertising, marketing and public relations ($13,435), education and training ($2,308), and machinery and tools ($2,817). A big chunk went toward creating a different brand that never ended up seeing the light of day. Before starting MOODEAUX, Arps planned to launch a brand called Moode Beaute in 2018.

“The biggest mistake I made initially was not doing my research,” she recalls. “I didn’t do any trademark searching or whatever. I just ran with my idea.”

After coming up with the name, she bought a domain for the website and hired a designer to work on branding and a logo, but a call from her lawyer forced her back to the drawing board: Someone else had already trademarked “Moode Beaute” two weeks before Arps, so she couldn’t use the name.

To make matters worse, she had just been laid off from her job. “I was gradually depleting my savings while working on a brand that I couldn’t even launch,” she says.

Arps pivoted and rebranded under the name MOODEAUX. Because she didn’t have a formal fragrance education, she spent her first year as a business owner researching fragrances and learning how to create a scent profile. “I was taking courses, watching YouTube, and talking to anyone I could get on the phone, including a fragrance formulator,” she says. After experimenting with oils and ingredients and figuring out what smelled good to her, she landed on a scent a year later. Together with her lab partner, it took about 10 tries to develop a fragrance that she loved.

She launched this past fall with her first scent, Worthy, a citrus, floral, and woodsy blend. The brand is sold direct-to-consumer via its website, and it breaks even. Arps is the company’s only full-time employee, but she doesn’t draw a salary. She still works full-time at a corporate job.

Scott estimates that her first round of spending was “probably around $500,” though her production costs increased as her brand grew. She started off with a line of 12 melanin-rich foundation shades and originally called her brand SKNY DIP Cosmetics.

She spent $150 on ingredients to make her foundations and packaging. She also used the website Sticker Mule to create the labels for her products, which could cost anywhere from $50 to $130, depending on how many labels are ordered. She made her own website with Squarespace for $25 a month and found an L.A.-based creator who only charged her $100 to design the packaging since she was just trying to build up her portfolio.

The company launched in May 2017 and four months later rebranded under the name Range Beauty. She quickly added four new products and expanded her foundation shade range from 14 to 21. In the end, the rebrand cost her $2,000. Since she was still working as an HR analyst, Scott funded her project using her salary.

“Along the course of maybe two or three years, I spent no more than $10,000 of my own money,” she said. In 2018, she brought in $20,000 in revenue. That number steadily rose to $45,000 in 2019 and $337,000 in 2020. Today, her products are sold directly through the Range Beauty website and Target.

When young Black entrepreneurs launch their businesses, the odds are stacked against them.

Black millennials with a bachelor’s degree earned an average salary of $44,498 in 2019—22 percent lower than the average salary of their non-Black peers, according to data collected in 2021 by Lending Tree.

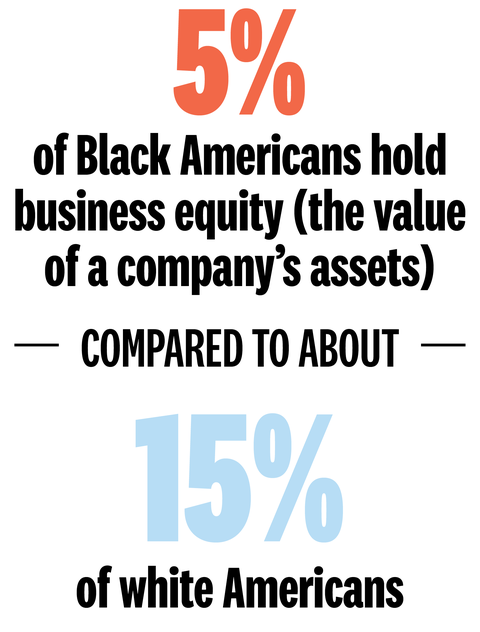

Black Americans have also never had an equal ability to reap the benefits of business ownership. Only 5 percent of Black Americans hold business equity (the value of a company’s assets), compared to about 15 percent of white Americans, per a 2019 report by McKinsey & Company.

And even if they manage to capture a piece of the pie, their morsel isn’t as lucrative: The average Black American’s business equity is worth about 50 percent of the average American’s and a third of the average white American’s. The study also found that Black business owners have a harder time securing capital and accessing networking opportunities than non-Black people.

Over the last few years, several beauty brands have launched initiatives designed to help small business owners of color receive funding. For example, Glossier offered $500,000 in grant money for Black business owners in 2020 as the country struggled to move forward in the wake of George Floyd’s death. Shortly after, Ipsy announced its plans to invest $5 million into the “development and amplification” of Black-owned beauty brands between 2020 and 2021.

In 2019, through a program sponsored by beauty guru and Forvr Mood founder Jackie Aina, Scott was awarded a $5,000 grant that she put back into her business. By December that year, she was able to quit her job to focus full-time on Range Beauty, thanks to a combination of sales revenue and funding secured from pitch competitions and grant programs.

“When I’m doing these pitching competitions, and I’m awarded financial support or mentorship, those are huge validating moments for me,” she says. “So many companies come across their table. And for them to see what I’m creating and to believe in it enough to help me, that helps keep me going.”

Arps has also received funding from these special programs. In 2021, MOODEAUX was awarded $25,000 from the New Voices Foundation in partnership with Pull Up For Change through a virtual pitch competition for up-and-coming Black women-owned beauty brands. “Besides capital, access to mentorship and service providers who’re willing to grow with me has been just as invaluable,” she says. “I’m incredibly grateful and humbled.”

While a growing number of initiatives are popping up to fund young entrepreneurs of color, the entire process is still emotionally taxing.

For Arps and Scott, navigating an industry that has failed Black women for so long can make the pressure to succeed even more pressing.

“Every little thing, big or small, really rests upon your shoulders,” says Arps. “I’ve had to say no to a lot of things.”

Scott struggled to find a community after moving from New York City to Atlanta to launch Range Beauty. “I was in a dark place when I felt like I didn’t have anyone around me who understood the gravity of what I was trying to do,” she says. “You go through certain things, and you’re like, I’m not making a lot of money. What’s wrong with my business? Why isn’t my revenue this amount? or Why isn’t this retailer trying to talk to me? All of these things happen and you’re like, Is this what I’m meant to be doing? or Is what I’m creating actually of value?”

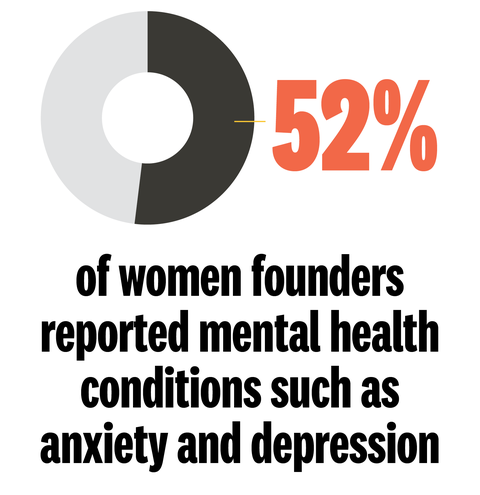

And they’re not alone: 52 percent of women founders reported mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression in a 2021 survey by the Female Laboratory of Innovative Knowledge (FLIK).

Scott’s first year of full-time entrepreneurship also coincided with the protests that swept the country following the murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery. “There were so many issues around Black Lives Matter and trying to get people to see us as human beings,” she recalls. “It was a lot while also trying to pay bills.”

So Scott began seeing a therapist: “It was the most amazing thing I could’ve done for myself.”

But in the Black community, negative attitudes around mental health care are common. Sixty-three percent of Black people consider having a mental illness as a sign of weakness, finds a 1998 study from the National Mental Health Association (now Mental Health America). This sentiment, paired with a lack of access to providers and many Black peoples’ widespread suspicion of healthcare workers due to racist and discriminatory practices, prevents many from seeking help.

As part of her commitment to mental health and providing resources to those who need it, Range Beauty donated a total of $3,000 to Therapy for Black Girls, HealHaus, and other organizations last year.

“Black entrepreneurs are working four times as hard for half of what a lot of non-Black entrepreneurs are getting—especially women,” Scott says. “That type of boulder on your shoulder is a lot of weight.”

Despite the stress, both founders tap into their purpose to fuel their drive to succeed.

“This dream isn’t gonna happen without me,” Arps says. “Sometimes you have to do things you don’t want to do to get to do the things that you want to do. I’m constantly prioritizing for the greater prize, which is building a brand that inspires people to flaunt how they feel and to connect with themselves and showcase all of themselves to the world.”

Arps is working on a second scent that she plans to launch later this year. “I no longer refer to us as a ‘small business,’” she says. “We’re growing, and I’m excited for our growth.”

Scott hopes to bring attention to the lack of dermatologists available in the Black community and help educate more Black consumers on skin conditions like acne and rosacea. She also plans to launch three new products, and she’s expanding the brand’s reach to make it available through more retailers.

The realities of being a beauty founder are more arduous than either founder ever expected. But seeing the finished products makes the struggle worth it.

Arps will never forget seeing her mom and grandma holding her fragrance bottle for the first time. “Just seeing how proud they were, that was one of the top five moments of my life,” she says.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

[ad_2]

Source link