Can Brooklyn Change the Conversation on Comprehensive Planning in New York?

[ad_1]

“Planning, for lack of a better word, is deeply unsexy,” says Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso as he describes The Comprehensive Plan for Brooklyn: a Vision for a Healthier, More Equitable Borough, the first borough-wide comprehensive plan in the city’s history.

New York is the only major city in the U.S. without a comprehensive plan, one document that maps all land uses for a city, addressing its physical elements for an extended period of time—on average about 20 years. In 1969, Mayor John Lindsay produced the Plan for New York City, a true comprehensive planning effort, but the City Council never adopted it.

As a City Councilmember, Reynoso tried to introduce comprehensive planning in 2019 and 2020, but his efforts largely failed to generate enthusiasm outside planning circles. While campaigning for the office of Borough President office, he promised to produce a plan. Now he’s done it, but there’s one catch: as Borough President, he has no legislative authority to implement it.

Campaign promises are usually simple and easy to rally support behind. Why would a candidate promise a planning document, let alone one he cannot implement? “This is an effort to inspire,” says Reynoso. “It’s about showing people there’s a better way to manage this city.”

Marcel Negret is a Senior Planner with Regional Plan Association (RPA), a non-profit that served as a research partner on the Brooklyn plan. “People have given up on an effort like this in New York,” he says. “Failures from the past make planners in the higher ranks and elected officials very skeptical of trying to do anything like this.”

In 2019 when New York City was revising its charter, Reynoso and Council colleagues unsuccessfully urged a Charter Revision Commission to propose a ballot measure on comprehensive planning. The next year, Council Speaker Corey Johnson issued a report proposing a comprehensive planning framework through legislation. “When Cory Johnson proposed his bill a few years ago, it was super wonky,” says Negret. “Part of the reason it failed is because very few people were able to understand what it really meant.”

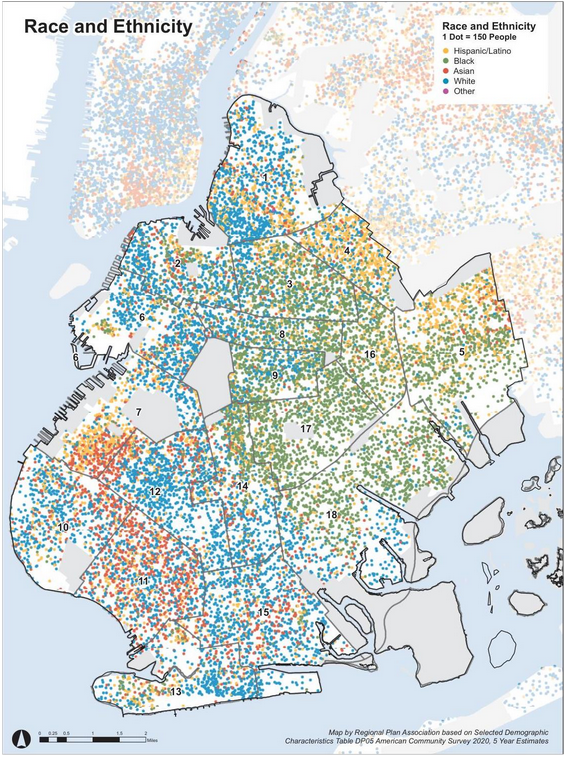

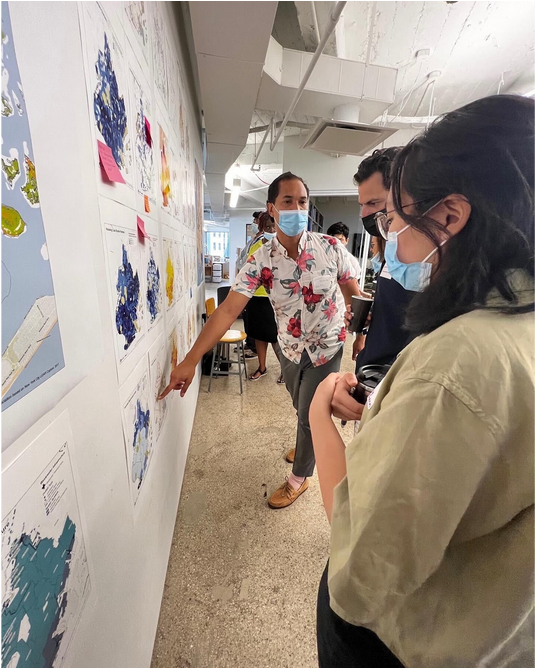

From these failures, Reynoso realized he had to make comprehensive planning more tangible. “You need to show people, you need to actually do it,” he says. To make the concept more accessible and exciting, the Brooklyn plan uses simple but shocking statistics and a rich array of visuals. “We have data and information that clearly shows a significant level of inequity that is grounded in bad planning. That stark disparity gets people riled up.”

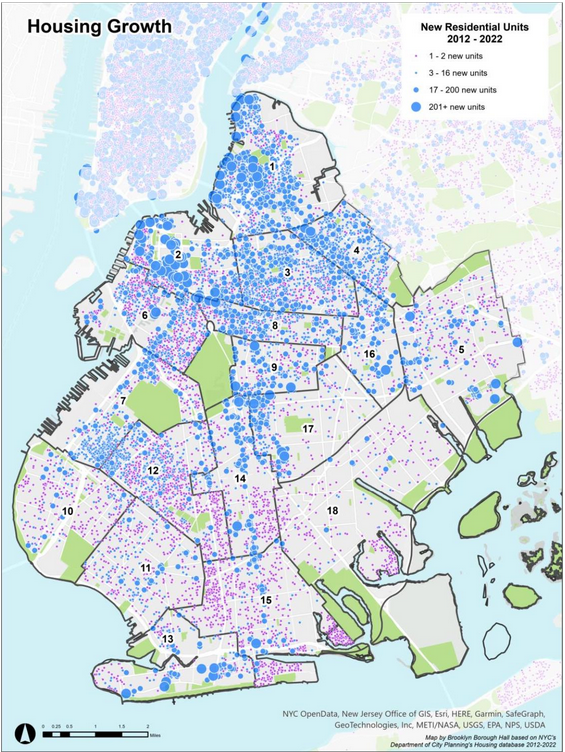

For example, between 2010 and 2020, Community District (CD) 5 in eastern Brooklyn, which includes East New York, New Lots, and Starrett City, created or preserved 12,106 units of affordable housing. Community District 10 in western Brooklyn, which includes Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, and Fort Hamilton, created or preserved seven units.

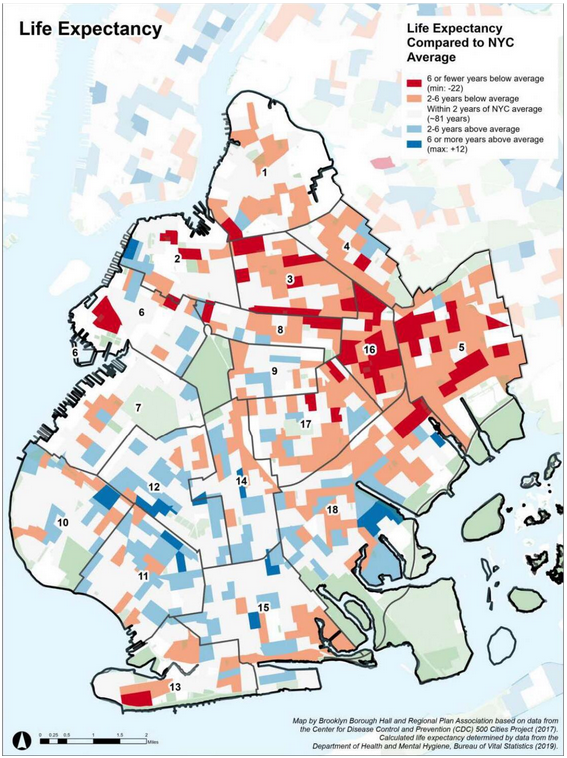

Life expectancy in CD 16 in Brownsville, a predominantly Black neighborhood in eastern Brooklyn, is 76 years, while life expectancy in CD 6 covering the predominantly white neighborhoods of Park Slope and Carroll Gardens is 82.9 years.

While the Brooklyn plan is 200 pages long, easy-to-read maps make up 60-70 percent of the document. “We live in an era in which a lot of information is consumed in a visual way. Planning efforts have to acknowledge that,” says Negret.

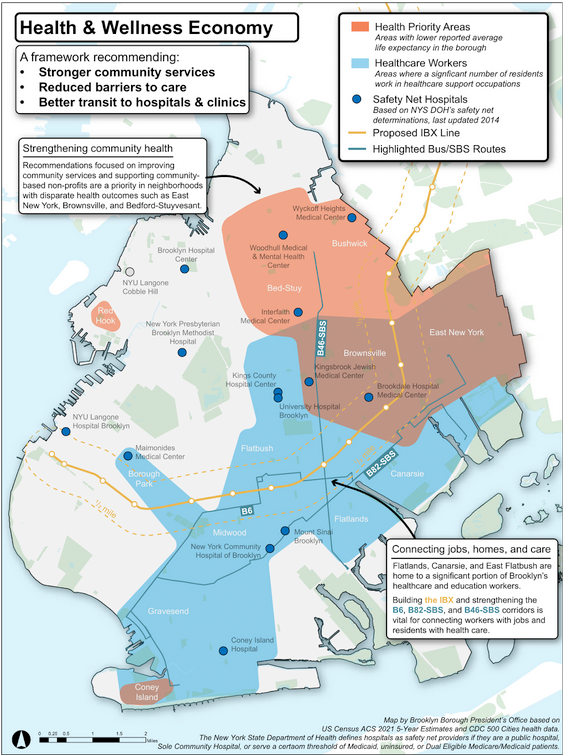

The plan pays special attention to health, specifically maternal health for Black women. In New York City, one in three deaths due to complications related to pregnancy take place in Brooklyn, and Black women are eight times more likely to die from such complications than white women. To address this, the plan makes maternal health the cornerstone of a larger framework called the Health and Wellness Economy.

“If you are pregnant, you need to have regular visits with your doctor,” says Dr. Kumbie Madondo, Director of Community Partnerships and Policy Solutions for the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM), which also served as a research partner on the Brooklyn plan. “But the doctor lives 10 miles from you and it takes you an hour and a half to get there. That’s a threat to your health because you end up missing doctor visits or not going at all.”

The plan identifies Health Priority Areas, where residents have lower life expectancies, and Healthcare Worker Areas, where a high proportion of healthcare workers live, both of which overlap in a Venn diagram that encompasses much of the area where Black Brooklynites live. (The borough is heavily segregated by race.)

Among many other interventions, the plan calls for improving transportation to better serve both of these areas. In particular, it calls for building the Interborough Express (IBX), an above-ground rail line running along existing tracks from Bay Ridge to Astoria, Queens, and creating a legitimate bus rapid transit system along Utica Avenue, one of eastern Brooklyn’s main north-south arteries.

This is what a comprehensive plan can do: it can align components of a city that would otherwise be managed separately to improve outcomes for residents. This intersectionality makes comprehensive planning an ideal tool for addressing the social determinants of health, which are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.

Giridhar Mallya studies the social determinants of health as a Senior Policy Officer with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. He also served in the Philadelphia Department of Public Health when the city was rewriting its own comprehensive plan in the early 2010s. As part of this process, the city hired a new planner who reported to both Public Health and the Department of Planning and Development.

“We said if we really want to create access to healthy foods and green space and opportunities to be active, then we can’t do it alone in the health department,” he says. “We need our colleagues in other agencies to help us design and implement the strategies.”

The Comprehensive Plan for Brooklyn isn’t the only large-scale proposal underway to change what gets built where in New York City. Mayor Eric Adams is also advancing ‘City of Yes,’ a far-reaching series of citywide zoning changes designed to make it easier to build affordable housing, support small businesses, and prepare for climate change.

“I see ‘City of Yes’ as an example of changing a chapter of a zoning handbook as opposed to a comprehensive plan which says the whole handbook needs to be reviewed,” says Reynoso. “I support the ‘City of Yes’ and think it’s a step in the right direction, but it isn’t comprehensive planning.”

In particular, the zoning amendments proposed under ‘City of Yes’ are not necessarily aligned with future infrastructure investments and capital projects, like the Interborough Express. This could have unintended consequences in Brooklyn.

‘City of Yes’ would make it easier and less expensive to build affordable housing on certain development sites near transit, for example by allowing preferential floor-to-area ratios or waiving requirements to build additional parking spaces. These changes would not apply to the IBX route because the transit line doesn’t exist yet, even though the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and New York Governor Kathy Hochul are pursuing plans to build it.

“If you don’t make a proactive effort to align the land use and the project implementation, you will favor opportunistic land grabbers who acquire the land just because they know it will become more valuable,” says RPA’s Negret, who also supports ‘City of Yes.’ He says if the city changed the zoning along the IBX route now, it would be easier to develop affordable housing nearby later. “That’s why it’s important to plan ahead. Incentivize the type of development you think would make sense along the corridor.”

Without comprehensive planning, New York City lacks a framework to align these processes. With comprehensive planning, the city could use zoning as a tool to capture the value derived from infrastructure investments and channel it toward public goods like affordable housing. “If you don’t do it in time, that value is going to be captured by somebody else,” Negret warns.

While City Hall has not yet embraced comprehensive planning, their zoning reforms represent a step in that direction. Inside Brooklyn Borough Hall, Reynoso will continue to advocate for the concept, which has become somewhat of a personal mission.

“Typically when you work on projects like this,” says NYAM’s Madondo, “the higher-up person is not always involved. But Reynoso was really hands-on, attending a lot of the meetings, providing feedback. He kept on saying ‘I want to be led by the data. I don’t want to be led by what I think I should be doing.’”

While Borough Presidents have none of their own legislative power, they can co-sponsor bills alongside Councilmembers. For now, until comprehensive planning becomes a reality citywide, Reynoso says he’ll partner with Councilmembers to advance recommendations from the Brooklyn plan. “While I don’t have the authority to make those changes legislatively, I do have the influence.”

[ad_2]

Source link