From better diagnosis and treatments to prevention, the state of Alzheimer’s and other dementias | MUSC

[ad_1]

As the state launches its first Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, an expert on dementia at the Medical University of South Carolina is offering a big picture look at the debilitating health condition, including:

- Innovative new ways to try to recognize who’s at risk.

- Efforts to diagnose patients earlier so they have better outcomes.

- New treatments, both approved and under study.

- South Carolina-specific issues that may surprise some.

That expert, Steven Carroll, M.D., Ph.D., is chairman of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at MUSC. He’s a scientist whose work is funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, among other organizations. He’s also the son of a woman suffering from the very condition he’s made a career of studying.

“My mother has advanced dementia. I think virtually everyone is touched by these diseases,” Carroll said.

Millions of Americans suffer from dementia – a number that may hit 14 million by 2060, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It can cause trouble with:

- Memory.

- Attention.

- Communication.

- Reasoning, judgement and problem solving.

- Visual perception.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. Other types include frontotemporal dementia, which the actor Bruce Willis has; dementia with Lewy bodies, which is related to Parkinson’s disease; and vascular dementia. Some people have more than one form of dementia.

That much we know. But there are still a lot of unknowns, or at least uncertainties, about dementia. That’s where Carroll and his work, including with the developing ADRC, come in.

Innovative ways to recognize who’s at risk for dementia

Doctors already know there are some risk factors for dementia, including:

- Getting older.

- Family history.

- Race/ethnicity (older African Americans are twice as likely to suffer from dementia as whites; Hispanics are 1.5 times more likely).

- High blood pressure.

- High cholesterol.

- Smoking.

- Traumatic brain injury.

Environmental factors such as air pollution may play a role as well, according to many scientists, including researchers involved in a recent meta-analysis at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

And all of that’s important. Those are things we can look out for, and in some cases, alter our behavior to prevent. But they’re not the only signs that dementia may develop.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers, things about the body that can be tested and/or measured, can be important indicators, too. They’ll be part of the focus of the ADRC, which is a collaboration between MUSC, Clemson University and the University of South Carolina. ARDCs fall under the umbrella of the National Institute on Aging. They turn research advances into improved diagnoses and care and find ways to treat and try to prevent Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

Biomarker tests for dementia include brain imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, blood tests and more. They cannot diagnose dementia alone – they have to be part of a larger assessment. And they’re not available, for the most part, except through specialty clinics and medical research sites.

But biomarker tests play an important part in dementia research, helping scientists spot early brain changes and look at the role of risk factors, among other things. Carroll talked about the South Carolina ADRC’s focus in this area.

“We’re going to look at things like blood and cerebrospinal spinal fluid for proteins that would tell us that someone is at risk for developing dementia. We’ll also have a digital focus, looking at using things like wearable technology to follow people and look for signs that they’re developing dementia.”

Knowing that a person has shown those signs can help researchers find the right people for clinical trials that test potential treatments and lead to a better understanding of all of the factors that can cause dementia.

Genetic testing

While biomarkers are all about measurement, genetic testing focuses on gathering data on dementia risk variants. That, too, will be a major focus of the South Carolina ADRC.

“We’re taking a deep dive into the genetics,” Carroll said. “We’re taking advantage of the In Our DNA SC project. They’re trying to sequence the exomes of a hundred thousand people in the state. I think the last time I checked, they had about 38,000 done.”

MUSC launched In Our DNA SC to offer no-cost genetic testing, providing results on participants’ risks for certain cancers and heart disease. The project is also creating a secure genetic and research database.

Carroll said the ADRC’s work with data from In Our DNA SC will allow scientists to build on existing knowledge about genes linked to dementias. “We know, for instance, a large number of genes that predispose you to develop Lewy body disease, which includes Parkinson’s. We know a lot of genes that are causative for the frontotemporal dementias. We know things that put you at risk for conditions such as hippocampal sclerosis. And so we know that’s an important part of it but how much is still sort of up in the air.”

Since a nuanced understanding of such work is up in the air, something the ADCR will work to change, the center’s work on genes related to dementia will be for research purposes, not diagnosis. The goal is to reach a better understanding of the role certain genes may play in causing dementia.

Sensory changes

Carroll said another way to recognize dementia risk involves sensory changes. “People with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s lose their sense of smell. Patients with Alzheimer’s also will have things going on with their vision. They have things going on with their motion.”

So scientists are trying to capture that, in some cases, through technology. “We know, for instance, that decreased stride length is a good indicator. We have a guy in my department named Chris Metts who has developed a very nice Apple-based app that does exactly that. He calls it Gene Doe,” Carroll said.

“And so the idea would be to get this out to people who would be at risk for developing dementia and say, ‘Your wearable tech can predict that you’re getting into the very early stages of dementia. You could become a candidate for treatment.’ So that’s where a lot of this is right now.”

Efforts to diagnose patients earlier so they have better outcomes

So those are ways to gauge risks. Carroll said it’s also important to find ways to measure the development of dementia much earlier than doctors are able to right now.

“We know that Alzheimer’s disease develops with a fairly stereotypic pattern. Something triggers inflammatory changes in the brain, and then after a bit of time, that begins to trigger the accumulation of amyloid, which begins to flow in plaques in the brain. And those changes are actually going on before the disease is clinically evident,” Carroll said.

“And then ultimately what happens is you begin to disturb the cytoskeleton of neurons and develop what are referred to as neurofibrillary tangles. And those are basically insoluble aggregates of cytoskeletal proteins that sort of glom up the works so that the neuron can’t really effectively transport materials out to the synapses, which is the business end of the cells. So at that point, it does become clinically evident.”

That’s later than he’d like to see. “We need to be able to identify those people who are triggering inflammation and getting into the very early stages of making amyloid and begin treatment with things like lecanemab. Then ideally, you’d have something that you could pretty much do this with all comers.” Lecanemab, brand name Leqembi, is a drug recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

Research is already underway to help doctors detect dementia earlier. A study at the University of Cambridge found that people who eventually were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease showed signs five to nine years earlier, including having trouble on tests involving problem solving and pair-matching. They were also more likely to have fallen and have worse overall health.

New treatments, both approved and under study

Once someone is diagnosed with dementia, they have a growing number of treatment options.

Medications can help with symptoms, including cholinesterase inhibitors, such as Aricept, Exelon and Razadyne ER, and memantine, brand name Namenda.

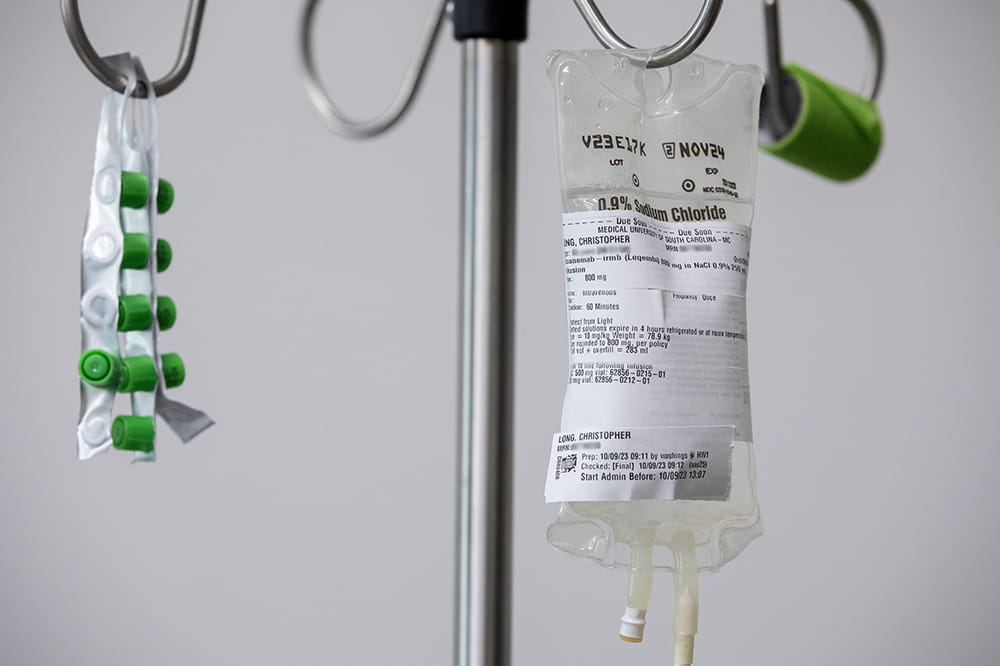

Leqembi, mentioned earlier, is available as well. And it’s now in use at MUSC Health. A Bluffton man became the first patient there to try the treatment. It works by removing amyloid, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, from the brain.

“I can tell you lecanemab does work. I have seen some autopsy series from people who had been treated with it. Their [amyloid] plaques are gone, but the patient still had dementia because their tau inclusions, the neurofibrillary tangles, were still there. So we’re making progress. It’s just that these are very complicated diseases.

Another amyloid-removing drug called Aduhelm got conditional FDA approval in 2021. But it was unclear whether it really slowed thinking and memory changes.

More potential treatments are in the works. “There are other drugs that are being tested that target some of the enzymes that are involved in producing the underlying pathology. And so there’s clinical trials ongoing with those as well,” Carroll said.

Dementia vaccines are also being studied. At this year’s American Heart Association Basic Cardiovascular Sciences Meeting, researchers talked about a vaccine that targets inflamed brain cells associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The hope is that it could potentially prevent or modify the course of the disease. However, it’s important to keep in mind that this testing was done in a lab, not on humans.

South Carolina-specific findings

As he and his fellow scientists look toward new treatments, Carroll is also interested in digging into something he’s observed in recent years. He leads the Carroll A. Campbell Jr. Neuropathology Laboratory at MUSC. There, his team examines the remains of people who died from neurological disorders, through its brain bank. Carroll has seen some surprising things in recent years.

“We’re trying to understand the epidemiology of what’s going on in the state. For some reason, I’m seeing a lot more early-onset Alzheimer’s. That’s Alzheimer’s that begins before someone is 65 years old. It’s about 20% of the cases of Alzheimer’s that we’re seeing in the neuropathology core. That should be about 5%.”

That’s not all. “On the other hand, if I look at the frontotemporal dementias, I’m seeing 20% more of one type than I should be seeing, and 20% less of the other. So things seem to be skewed. And that’s got us really wondering now if there’s something different going on in this state. And sort of on top of that, we know that, you know, we are one of the top states for dementia. In fact, I believe it was in 2017, we were No. 1 for deaths from dementia per capita,” Carroll said.

He’s also observed apparent geographic distinctions.“We have hotspots in the state. For instance, up in the northwest corner of the state, we have a very high instance of these diseases. The Pee Dee is also very high. And then we’ve got an area right here on the coast in the Lowcountry that’s very high as well. And if you dig down into those numbers and take a look at each of these different areas, the forms of dementia we see differ from area to area,” Carroll said.

“So again, is that genetics? Is it environmental? Is it both? We don’t know yet, but you know, that’s sort of the first step toward getting the base data you need to begin working with epidemiologists to get a handle on that.”

The answers may one day give families like his more information as they care for loved ones with dementia. “I’m not convinced my mother’s dementia is Alzheimer’s. And the reason I’m not is that she has aphasia. She has not spoken in several years. A primary progressive aphasia often goes with frontotemporal dementias, and a lot of those have a genetic basis,” he said.

“Well, in keeping with that, her brother just died with the same disease last March. Her mother died with that disease. All of her uncles on that side had the disease. This begins to make me ask, ‘Do we have a genetic cause for this? And if so, do I need to test her to find out?’”

“This is a discussion that we’re having among my siblings. And it’s a conversation that’s probably like the one a lot of families have had.”

[ad_2]

Source link