Perspective: Racism in Academic Medicine Is Hindering Progress Toward Health Equity

[ad_1]

Time and time again, scientific reports and surveys cite some version of the following findings: Black people have the worst health outcomes. Black patients have better health outcomes when they see Black doctors. Black patients prefer Black doctors. Black doctors tend to care for higher proportions of Black patients than their White counterparts.

Yet 53% of Black people in the US say it’s hard to find a Black doctor, which is not surprising. While Black people account for roughly 13% of the US population, they make up only 4% of the physician workforce and 7.3% of medical students. These representational disparities haven’t changed appreciably in decades.

We cannot achieve health equity for Black patients without expanding the Black physician workforce, and the nation’s medical institutions are not achieving that goal. When confronted with this problem, academic medicine leaders attribute the plateauing of the Black physician workforce to factors beyond its control — things like disparities in primary education and poverty. Medical institutions have yet to honestly examine and address how they perpetuate the problem of a White-dominated physician training system that unjustly excludes, punishes, and dismisses Black medical students, trainees, and attending physicians.

White people must recognize that inclusion is not a zero-sum game, said Camara Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, a Black physician who served as the 2021-2022 UCSF Presidential Chair. “It’s like they feel as if they’re sitting at a potluck,” she said. “They see you come in, and they don’t want you anywhere near the table because they think you’re going to come eat up all the food. . . . They don’t see that you’re bringing all kinds of cakes and pies and roasts.”

This phenomenon is neither new nor accidental.

The First Black Physician in America

Born into slavery, Dr. James McCune Smith was the first Black person to earn a medical degree and practice medicine in the US.

He graduated in 1837 from the University of Glasgow in Scotland (no American college would admit him) and then opened a medical practice in his native New York City. He was a leading intellectual and abolitionist until his death in 1865.

After Smith won his medical degree, another decade passed before a US school, Rush Medical College in Chicago, graduated a Black medical student, Dr. David Jones Peck.

From the day it was founded in 1847, the American Medical Association (AMA), the nation’s first and largest physician association, excluded Smith, Peck, and all other Black physicians. Most local and state chapters of the AMA did not admit Black members until the 1960s. Without membership in local and state medical societies, especially in the South, Black physicians were denied referrals, hospital admitting privileges, medical licensure, and training opportunities. Not until 2008 did the AMA formally apologize for its long history of racist practices targeting Black physicians. The legacy of those practices remains with us today.

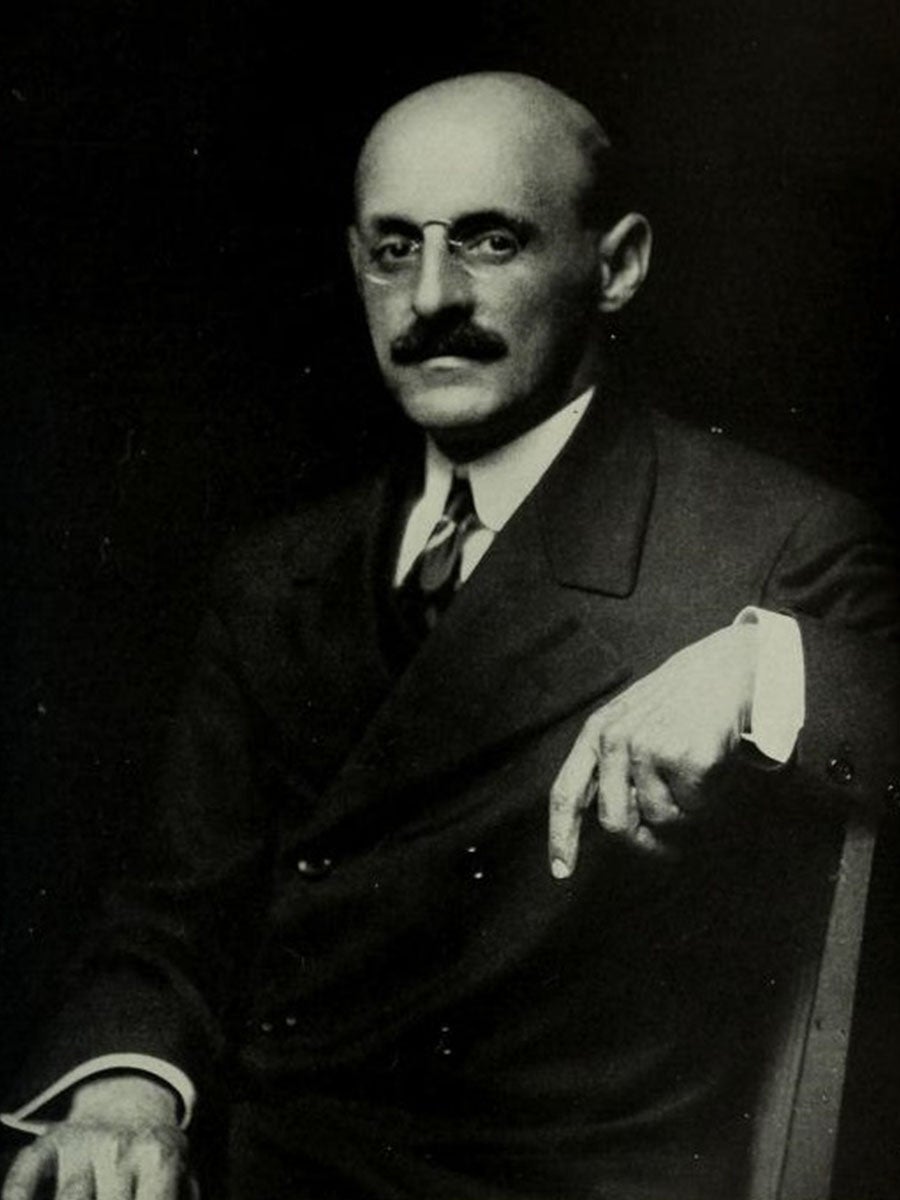

The Flexner Report

Perhaps the pivotal event in the history of Black medical education came in 1910, when educator Abraham Flexner published a report intended to spark reforms and modernization of US medical schools. It was an unashamedly racist document with grave consequences for health equity. Even though Flexner devoted relatively little attention in the report to historically Black medical schools, the document’s discriminatory language devaluing Black physicians was devastating. The findings ensured that impoverished Black medical schools, which needed far more funding than tuition revenue to finance facility upgrades and improved training, could not meet the requirements.

Ultimately, five of the nation’s seven Black medical schools shut down soon after the report. Flexner considered only two of them to be worthy of development, Howard University College of Medicine (founded in 1868) in Washington, DC, and Meharry Medical College (1876) in Nashville, Tennessee.

This reflected Flexner’s view that Black physicians should be trained differently from White ones, primarily because “10 million [Black people] live in close contact with 60 million Whites.” Since he considered Black people “a potential source of infection and contagion,” he said that Black physicians should be trained as “sanitarians” for “hygiene rather than surgery” to protect White people. This racist recommendation limited career opportunities for Black physicians and blocked progress toward health equity, since many of the surviving medical schools would not admit Black physicians for many years or decades.

The legacy of the Flexner Report remains highly relevant today. In the 113 years since it was published, only two new medical schools dedicated primarily to training Black physicians have been established in the US: the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles (1970) and the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta (1975).

(There are some encouraging signs the landscape is changing. On October 18, 2022, Drew officials announced they had received approval (PDF) to launch an independent medical school training program to augment the joint medical degree program Drew has long operated with UCLA. In recent months, two historically Black colleges or universities announced plans to open medical schools. The proposed Maryland College of Osteopathic Medicine at Morgan State University hopes to enroll students at a Baltimore campus starting in 2024. Last month, Xavier University and Louisiana health care giant Ochsner Health announced a partnership to open a new College of Medicine in Louisiana.)

As a result of more than a century of limited growth in Black medical institutions, most Black physicians today are trained at predominantly White institutions. The numbers haven’t changed much in decades. While medical schools have admitted more students from Black, Latino/x, and other marginalized groups, these efforts have failed to increase the Black physician workforce. One reason is that they don’t address discrimination that occurs farther down the training pipeline. While only 5% of resident physicians in training are Black, Black medical residents account for 20% of expulsions from residency programs.

Defenders of the status quo argue that disparate dismissal rates are evidence that affirmative action doesn’t work, and they equate more diversity with less excellence. This viewpoint ignores the generational effects of racial exclusion and marginalization. It also fails to acknowledge that while Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores predict good grades in the first year of medical school, scores alone do not predict one’s ability to be a great doctor.

According to accounts from many Black medical trainees and faculty physicians, the real reason for these higher dismissal rates is racism.

Unconscious Bias

Too many academic medical institutions tolerate intimidation, stigmatization, retaliation, and a continuous barrage of slights that push promising Black doctors out of medicine.

These micro- and macroaggressions are hugely disappointing to Black people who want to be physicians, and they are catastrophic for people of color who need care provided by doctors who look like them. It’s a tragedy.

“I’ve seen firsthand where a staff or faculty member may make a statement without facts or may try to make decisions, and it is rooted in unconscious bias — and then, at some level, explicit bias,” said Deborah Deas, MD, MPH, the Black vice chancellor for Health Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, dean of its medical school, and a professor of psychiatry.

“It is a loss of our genius that saps the strength of the whole society,” said Camara Jones. “The loss is not recognized because people think that they have everybody at the table that they need without us. They don’t value us.”

Medical Student Silenced by Proxy

Jane, a Black student at a California medical school, shared with me a recent incident involving her Black classmate, Dianne. (To protect their privacy and honor concerns about jeopardizing their careers, I won’t share the students’ real names or identifying details.) In a small group setting where Dianne was the only Black person, the faculty leader made a joke that classmates in the room found funny. Dianne said she found it racially offensive. When Dianne shared what happened with Black peers in a private group chat, they reacted as she did. When the existence of that private chat was leaked to a senior official of the school, the official downplayed the faculty leader’s behavior and publicly admonished Dianne for being overly sensitive, she said. Later, the official privately implied to Dianne that she would be expelled if she didn’t drop the matter, she said.

To Jane, the public admonishment was a clear message that the school would not take seriously the concerns of Black students about racial insensitivity. In a health care system that is increasingly focused on matters of health equity, these students were effectively silenced about a critically important racial issue. This dismisses the impact of these affronts on Black students and communicates that these future physicians are not valued.

“I would never report anything unless it was so explicit that nobody could say that this is in my head,” Jane said. “It would have to go as far as probably someone calling me, like, the N-word.”

Black Resident Physicians Culled

STAT, the online health, medicine, and life sciences news platform, published a two-part investigation in June that reported young Black physicians are forced out of US training programs for minor errors that are overlooked when committed by their White counterparts. In the articles, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Usha Lee McFarling wrote: “Black residents either leave or are terminated from training programs at far higher rates than White residents. The result of this culling — long hidden, dismissed, and ignored by the larger medical establishment — is that many Black physicians have been unable to enter lucrative and extremely White specialties such as neurosurgery, dermatology, or plastic surgery. It’s a key reason these fields have been unable to significantly diversify their ranks even as the total number of residency spots has increased nationally.”

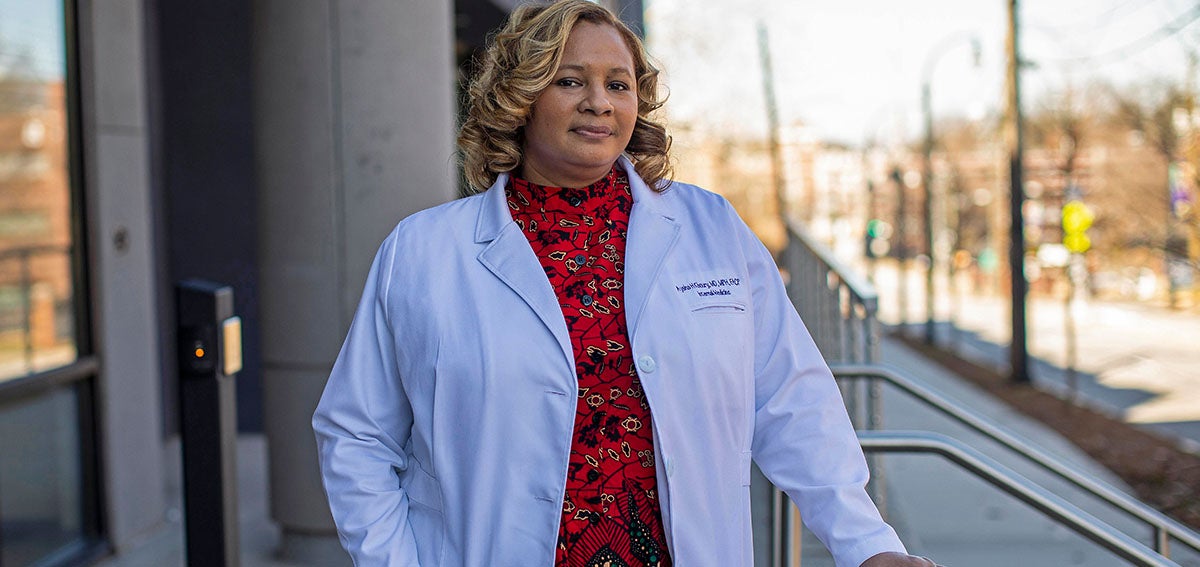

Medical Professor Forced to Exit

The experience of Aysha Khoury, MD, a Black internist and faculty member at Kaiser Permanente School of Medicine (KPSOM) in Pasadena, illustrates how efforts to control and silence Black physicians can occur at any point in a Black physician’s career. In August 2020, Khoury facilitated a discussion about race and gender health bias with a small group of students in the KPSOM inaugural class. Within hours, the medical school suspended Khoury from teaching and clinical responsibilities. After an eight-week probe during which all the students in that small group petitioned for her reinstatement, the administration dismissed Khoury. The school told her the firing was a consequence of poor clinical and teaching performance, not racism.

|

Black Patients’ Voices Listening to Black Californians is a CHCF-supported study to understand Black Californians’ experiences of racism and The project identifies policy actions and practice changes at the clinical, administrative, and training levels that policymakers and health system leaders can make to eliminate the impact of racism on Black Californians’ experiences in health care and to improve their health outcomes. |

Khoury, who said she was never told what policy she violated, sued the school. “My career with Kaiser is over now because the dean, the executive leadership, and the board all okayed my dismissal,” said Khoury in an interview on June 22, 2021. “They gave students a primer on how to discriminate and get away with it.” The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) concluded that her claim that KPSOM’s action violated the National Labor Relations Act was meritorious and filed its own separate complaint.

On January 10, 2023, Khoury and KPSOM jointly announced the settlement of the civil case and the NLRB proceeding. “The settlement includes a demonstrable commitment by the school to conduct further examination of its practices relating to diversity, equity, inclusion, and implicit bias in medical education and to enhance those practices as well as share learning to positively influence medical education overall,” the joint statement said.

Khoury is now a faculty member at the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Stream of Lawsuits

In August 2022, Derrick Morton, PhD, a Black biologist and former KPSOM assistant professor, filed a lawsuit against the school (PDF). Morton alleges that he was “repeatedly traumatized” by KPSOM’s “pervasive hostility against Black professionals and medical students.” White supervisors “demoted, isolated, and constructively discharge[d] the [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] associate dean because he is Black,” Morton asserts. He said widespread anti-Black animus blocked Black faculty members from associating with each other or with Black students to protect their careers. Morton departed the school for a new job. A KPSOM spokesperson said school officials “strongly disagree with the allegations and characterization of events” in Morton’s complaint. The spokesperson declined to provide further information.

Institutional race discrimination against Black physicians and trainees is depressingly common, regardless of the medical, economic, or geographic setting. In California, Omondi Nyong’o, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist in Palo Alto, and several other Black physicians have lodged complaints and filed lawsuits against Sutter Health, alleging racial discrimination at the large Sacramento-based nonprofit health system. A Sutter spokesperson issued a statement: “We deny having taken or participated in any discriminatory or retaliatory conduct against Dr. Nyong’o or any of our physician partners or our own employees.”

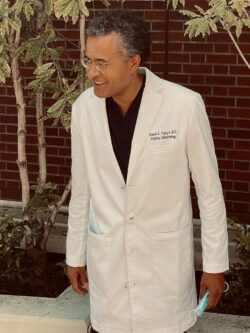

In Louisiana, Princess Dennar, MD, the Tulane University School of Medicine’s first and only Black woman residency program director, was suspended from her job soon after filing a race discrimination lawsuit against the school. The case was settled in December 2021, and the parties have made no public comments since.

A growing number of Black physicians are speaking out. Uché Blackstock, MD, wrote an article in STAT about “toxic and oppressive” conditions that prompted her to leave a faculty position in an academic medical center.

I described my own similar experience in the New England Journal of Medicine. There are many similar stories around the nation, but most unfold beyond the media’s gaze.

Little Change in Representation

The racial disparities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic starting in 2020 coincided with police murders of unarmed Black people. Americans from many backgrounds were galvanized by these events, and it was common for medical institutions to join public and private organizations in denouncing racism and recommitting to diversity. Since that time, however, the definition of “diversity” within many organizations broadened to the point that the benefits of these actions to Black Americans have been attenuated.

The approach appears to have shifted away from “Black lives matter” and toward “all diversity matters,” enabling institutions to lump together counts of women and non-White physicians and trainees to project a feel-good, progressive façade. Behind the numbers, however, there often is little or no change in overall representation of Black populations — especially in the ranks of senior leadership.

There has been a notable lack of Black physician advancement in academic medical institutions, and pay disparities have been well documented. According to a 2021 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges, only 3% of academic medical school full professors are Black women, and only 1.7% are Black men. Among clinical science department chairs, only 1.8% are Black women and 2.8% are Black men. Among physician faculty, for every dollar a White man is paid, on average a Black man is paid 93 cents, a White woman 77 cents, and a Black woman 73 cents.

Achievements in academia are not the only measures of a successful medical career and academic settings are not the only settings where physicians can practice and serve their communities. But it is undeniable that academic institutions are where decisions are made regarding who makes up the next generation of physicians and how they are trained, mentored (PDF), and treated.

The ‘Minority Tax’

While Black faculty in academic medical institutions are burdened by racism, they also pay a “minority tax” that impedes career advancement. This penalty is levied in the form of substantial amounts of time they are expected to devote to service on committees, panels, and boards on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Such service is usually uncompensated and contributes to a façade. It is a time commitment not expected of White colleagues, who stay focused on activities that lead to promotions, including research and publication.

Underscoring Jones’ point about Black doctors being chronically undervalued, a study examining applications for federal health research grants found Black researchers’ applications from 2011 to 2015 were more likely to be overlooked, less likely to be considered fundable, and focused on topics with lower award rates. The irony of this finding is that after George Floyd’s murder, well-funded scientists who are White and have relatively little background in health equity research are disproportionately being awarded grants in that field. Their scientific endeavors often build on the research of Black and Latino/x scholars without citing them or offering to include them on grants or as co-authors.

This must change.

An Agenda for Progress

We need to redefine the medical training “pipeline” as more than just ensuring increased numbers of Black people gain admission to medical school. The pipeline needs to include meaningful support throughout medical school and in subsequent years as physicians assume leadership positions. This will require acknowledgment of the historical and ongoing role of medical institutions in allowing disproportionate numbers of Black doctors to fall out of the pipeline.

This will require a culture shift. Meaningful change will require action.

Medical institutions need to embrace the reality that people from different backgrounds add value to the enterprise and should be treated and paid equitably. These organizations should stop creating diversity offices and committees that lack funding and authority to take concrete actions to improve the situation. They must stop punishing Black students and physicians for objecting to racist interactions.

“We all need to recognize that the dearth of Black physicians is sapping the strength of our whole society and that inaction in the face of need is a hallmark of how structural racism often manifests today,” said Jones.

As Frederick Douglass, who escaped enslavement to become an internationally renowned abolitionist, famously said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did, and it never will.”

The time to demand change is now.

[ad_2]

Source link