New KFF Survey Documents the Extent and Impact of Racism and Discrimination Across Several Facets of American Life, Including Health Care

[ad_1]

In a reflection of how pervasive racism and discrimination can be in daily life, a major new KFF survey shows that many Hispanic, Black, Asian, and American Indian and Alaska Native adults in the U.S. believe they must modify both their mindset and the way they look to stave off potential mistreatment during health care visits.

KFF’s 2023 Survey on Racism, Discrimination and Health, the first in a series, also documents the pernicious association of racism and discrimination with worse health and well-being, including heightened tendencies toward feeling anxious, lonely, or depressed.

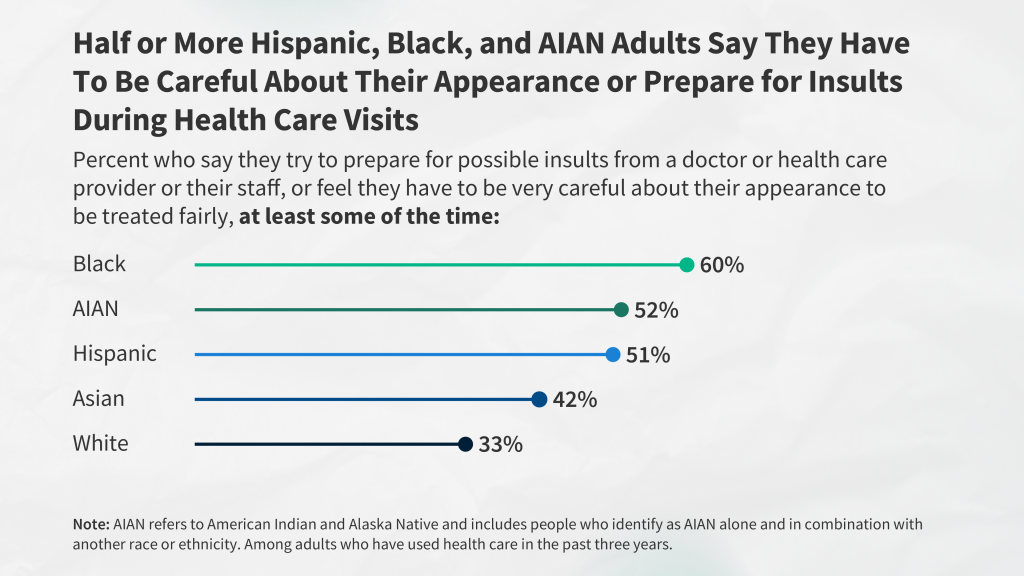

The large, nationally representative survey finds that among those who used health care in the past three years, six-in-10 (60%) Black adults, about half of American Indian and Alaska Native (52%) and Hispanic (51%) adults, and four-in-10 (42%) Asian adults say they prepare for possible insults from providers or staff and/or feel they must be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits at least some of the time. In addition, one-third of White adults report doing these things.

Such preparations, behaviors documented in other research arenas as “heightened vigilance,” likely are a response to past experience, the survey suggests. A third of adults overall report at least one of several negative experiences with a health care provider in the past three years, and many Black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian and Alaska Native adults say they were treated this way because of their race or ethnicity.

The negative experiences asked about in the survey include a provider assuming something about them without asking; suggesting they were personally to blame for a health problem; ignoring a direct request or question; or refusing to prescribe pain medication they thought they needed. About a quarter (24%) of Black adults and one-in-five (19%) American Indian and Alaska Native adults say they experienced at least one of these and that their race or ethnicity was a reason why they were treated this way, as do 15% of Hispanic adults and 11% of Asian adults, compared with just 4% of White adults.

For example, 22% of Black adults who were pregnant or gave birth in the past 10 years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed, roughly twice the share of White adults with a pregnancy or birth experience (10%).

Having a shared racial and ethnic background between provider and patient often is associated with more positive interactions, the survey finds.

The survey is part of a major effort by KFF to document the extent and implications of racism and discrimination across many aspects of American life, including people’s interactions with the U.S. health care system. It provides new data on individuals’ experiences with racism and discrimination and the impacts of these experiences on health and well-being. The survey also sheds light on how structural inequities in American society and experiences with racism and discrimination vary within racial and ethnic groups by factors such as income, gender, skin tone, age, and LGBT identity. Future KFF analyses and surveys will explore additional topics and delve deeper into results for specific populations.

“While there have been efforts in health care for decades to document disparities and advance health equity, this survey shows the impact racism and discrimination continue to have on people’s health care experiences,” said KFF President and CEO Dr. Drew Altman. “And people in the survey reported that racism and discrimination have affected not only the care they get, but also their health and well-being,” he added.

Experiences with racism and discrimination are prevalent in daily life, and are associated with worse health and well-being

The survey reveals that at least half of American Indian and Alaska Native (58%), Black (54%), and Hispanic adults (50%) and about four-in-10 Asian adults (42%) say they have experienced at least one type of discrimination in daily life at least a few times in the past year. These experiences include receiving poorer service than others at restaurants or stores; people acting as if they are afraid of them, or as if they aren’t smart; being threatened or harassed; or being criticized for speaking a language other than English. Black, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Asian adults are more likely to attribute these experiences to their race or ethnicity compared to their White counterparts.

Among Black adults, those with self-reported darker skin tones report more discrimination. Black adults who say their skin color is “very dark,” “dark,” (62%) or “medium” (55%) are more likely to report an experience with discrimination than Black adults who say their skin color is “very light” or “light” (42%).

Specific discrimination experiences also vary by gender, with Black men being the most likely to say people act as if they are afraid of them (27%) and Hispanic women most likely to say they are treated as if they are not smart (37%).

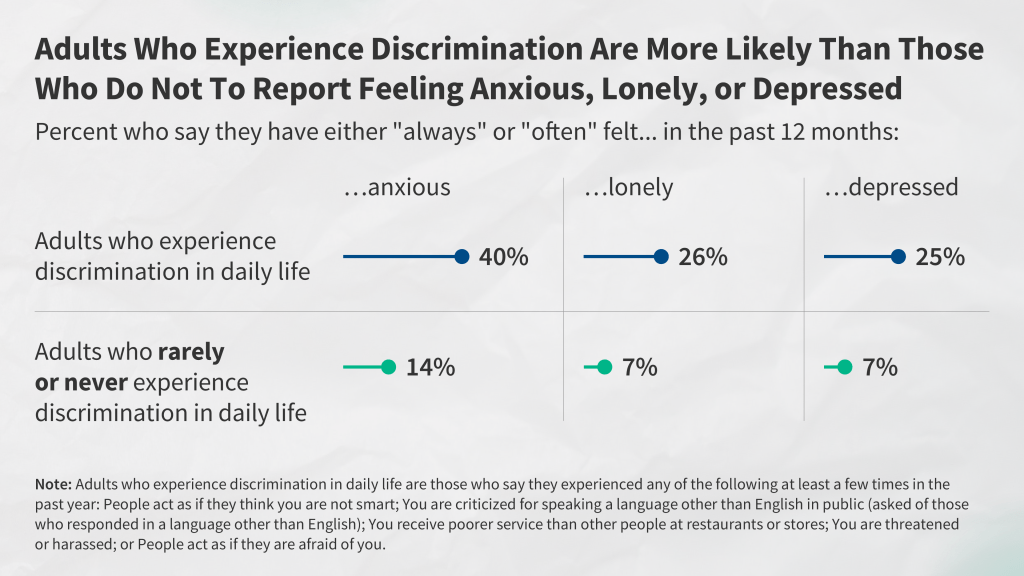

The survey suggests that experiences with racism and discrimination contribute to, or are associated with, reported worse health and well-being. People who experienced discrimination in their everyday lives at least a few times in the past year are more than twice as likely as those who report rarely or never experiencing discrimination to say that in the past year, they “always” or “often” felt anxious (40% vs. 14%), lonely (26% vs. 7%), or depressed (25% vs. 7%). These patterns are similar across racial and ethnic groups and persist even after accounting for other demographic characteristics.

A shared racial and ethnic background between provider and patient is associated with more positive interactions

The survey finds that Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults who have more health care visits with providers who share their racial and ethnic background report more frequent positive and respectful interactions.

For example, Black adults who had at least half of recent visits with a provider who shares their background are more likely than those who have fewer of these visits to say that their doctor: explained things in a way they could understand (90% vs. 85%); involved them in decision making about their care (84% vs. 73%); understood or respected their cultural values or beliefs (84% vs. 76%); or asked them about their work, housing, or access to food or transportation (39% vs. 24%) during recent visits.

However, reflecting limited racial and ethnic diversity of the health care workforce, at least half of Black (62%), Hispanic (56%), AIAN (56%) and Asian (53%) adults who used health care in the past three years say that fewer than half of their visits were with a provider who shared their racial and ethnic background. In contrast, about three-quarters (73%) of White adults say that half or more of their visits were with a provider who shares their racial and ethnic background.

This survey is part of a broader body of work that builds on KFF’s commitment to amplifying the voices of marginalized populations, including the recently released 2023 KFF/LAT Survey of Immigrants, which provides insight into experiences of immigrants by different factors, including immigration status.

The KFF Survey on Racism, Discrimination and Health is a probability-based survey conducted online and via telephone with a total of 6,292 adults, including oversamples of Hispanic, Black, and Asian adults conducted June 6-August 14, 2023. Respondents were contacted via mail or telephone; and had the choice to complete the survey in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese. Survey methodology was developed by KFF researchers in collaboration with SSRS, and SSRS managed sampling, data collection, weighting, and tabulation. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus two percentage points for results based on the full sample; three percentage points for results based on Hispanic adults (n=1,775), Black adults (n=1,991) or White adults (n=1,725); five percentage points for results based on Asian adults (n=693); and eight percentage points for results based on American Indian and Alaska Native adults (n=267).

[ad_2]

Source link