Off the rails of democracy – Communist Party USA

[ad_1]

Rage and confusion over the recent Supreme Court decisions is sweeping the nation. The Roe v. Wade decision (1973) establishing women’s reproductive rights has been repealed. A New York State law prohibiting the carrying of concealed guns, passed in response to escalating shootings and deaths, has been declared unconstitutional. The court has sharply reduced the regulatory powers of the Environmental Protection Agency, established in 1970. This comes after decades of scientific research showing the dangers of climate change and global warming.

What is the logic behind this, and what as Marxists and Communists can and should we do to challenge and defeat these policies?

There is a standard used in philosophy which should be applied to the Court’s recent decisions. Statements, or assertions, should be judged by their “validity and reliability.” Are they true statements in terms of logic, reason, and consistency (validity)? Is the evidence (facts, data) used to support the statement true (reliability)? I will use this standard as a Marxist historian to look at the Court’s rulings.

The Court doctrine of original intent is not valid

The judicial decisions have always reflected the political economy and class and social relations. The Constitution was a political compromise among merchant capitalists, landlords, slaveholders, creditors, and debtors on a variety of issues — slavery, the payment of debts, and the regulation of trade.

It cannot be interpreted like the Jewish Torah, the Christian Gospels, or the Muslim Koran — sacred, unchanging texts. And the Supreme Court has no right to interpret legislation passed by Congress or the directives of the president, since the Constitution did not give the Court the power of judicial review.

However, that power was in effect taken by the Court in 1805 in a brilliant maneuver by Chief Justice John Marshall in Marberry v. Madison. The court has maintained the power of judicial review for over two centuries, often adjusting its interpretations to major changes in society.

The representatives who drafted and approved the Constitution, much less the former colonies/states which ratified it, all rejected the principle of universal suffrage. The leaders of the revolution associated the term “democracy” with mob rule. Property qualifications for voting in federal elections was the established rule. If one took the original intent seriously, the Court would have the power to establish property qualifications for voting, since there is no constitutional amendment abolishing property qualifications for voting, just as there are constitutional amendments abolishing slavery and giving women the right to vote.

The Supreme Court’s recent decisions are not reliable

When the Constitution was drafted and enacted, English common law defined life as existing when a fetus could be felt moving or kicking in the mother’s womb, called “quickening.” If the mother claimed that the fetus had been aborted before this “quickening,” she was held harmless. Laws banning abortion and contraception, and pamphlets and manuals about both in the mails, were enacted at the state and federal levels in the late 19th century as part of a movement led by the Reverend Anthony Comstock, organizer of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. These laws were part of a backlash against the growing movement for women’s civil rights, equality under the law, and the right to vote. The women’s rights/women’s liberation movement of the 1960s, following in the path of the civil rights/Black liberation movement, led the successful campaign to repeal these laws, which finally resulted in Roe v. Wade, a century after they began to be enacted.

The Court’s decision invalidating a New York state law prohibiting the carrying of concealed handguns is also unreliable. Here the evidence is direct and incontrovertible. The Second Amendment to the Constitution states, “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” But in English law and in colonial theory and practice, as Joshua Zeitz in an excellent analysis argues, the amendment never meant that all citizens had the right to bear arms. This right “was inextricably connected to the citizen’s obligation to serve in a militia and to protect the community from enemies domestic and foreign.” And “well-regulated militias” meant militias constituted by legitimate authorities, not private groups like the later KKK, Nazi storm troopers, or self-proclaimed state militias.

Zeitz makes the important point that James Madison, a major author of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, had earlier drafted legislation in the Virginia legislature barring individuals from openly carrying and displaying guns, like the present New York State law that the Court has declared unconstitutional. The purpose of the amendment was clearly to prevent a government from doing what Britain did in the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party: disperse the colonial legislature and its militia and in effect declare martial law. Also, the guns in question fired single “balls,” not bullets, and had very limited range and accuracy. Today’s AR-15 rifles, for example, used in recent mass shootings, have greater fire power and accuracy than the assault rifles used during World War II and the Korean War.

The Supreme Court’s other decisions on the regulatory powers of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the right of a school employee to engage in religious action, are neither valid in their relationship to the Constitution nor reliable in regard to their factual assertions. They are a repudiation of more than a century of law and policy of the federal regulation of industry and the post–Civil War 14th Amendment defending the civil rights and liberties of citizens from their infringement and/or denial by the states.

The revival of “original intent”

The Supreme Court and the judiciary have been the most conservative section of the federal government throughout most of U.S. history. The fact that the justices are not elected and can be removed only through impeachment, resignation, or death explains this.

The courts have in the past and once more in recent decades used the Commerce Clause of the Constitution to declare unconstitutional legislation that regulates business and promotes social welfare. Beginning in the 1880s, they declared corporations “persons” to give them 14th Amendment protections from regulation and taxation by the states, and have over and over again used the 10th Amendment to support states’ rights.

The political nature of the Supreme Court from its very inception is indisputable. The Court, for example, represented the interests of the slaveholder class from the administration of George Washington (himself a slaveholder) up to the Civil War.

The political nature of the Supreme Court from its very inception is indisputable. The Court, for example, represented the interests of the slaveholder class from the administration of George Washington (himself a slaveholder) up to the Civil War.

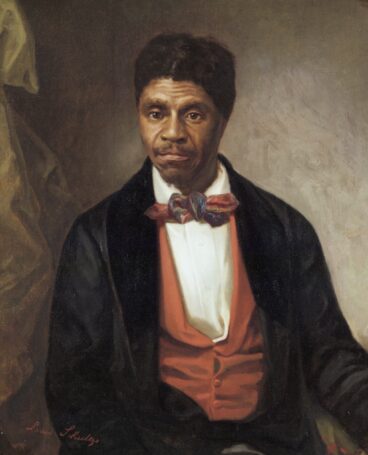

But as the nation changed, industrial capitalism grew, and the anti-slavery movement became broader, the demands of the slaveholders and the actions of their Supreme Court became more extreme. The Dred Scott decision (1857), which in effect repealed the earlier restrictions on the expansion of slavery in the Western territories, supporting legislation advanced by pro-slavery congresses and presidents, reflected this development. As an afterthought, the slaveholder-dominated Supreme Court claimed that the authors of the Constitution had not intended any Black person, slave or free, to have the rights of an American citizen, an expression of “original intent” which both enraged and strengthened the increasingly militant anti-slavery national coalition.

With the defeat of the Confederacy, slavery was abolished through constitutional amendment in all the states, and the former Confederate states now under Union army occupation had to ratify the amendment to regain admission to the Union. With the support of President Andrew Johnson, a pro-Union former senator from Tennessee (and himself a former slaveholder), they did so while enacting labor codes that in effect declared the former slaves to be unemployed vagrants and returned them to the “custodial care” of their former owners.

In response to these acts, Thad Stevens, Charles Sumner, and other militant anti-slavery leaders of the Republican Party proposed a second constitutional amendment to establish national citizenship and protect the civil rights and civil liberties of the nearly 4 million former slaves. They did this for two reasons. They feared that President Johnson would veto the civil rights legislation they were advancing in Congress. And even if they were able to override his veto, they feared that the Supreme Court, where the now former slaveholders remained a powerful force, would declare such legislation unconstitutional.

The 14th Amendment establishing national citizenship was passed, followed by the 15th, which extended the right to vote. However, the war was a victory for the industrial capitalists and their banker allies, who within a generation betrayed both the former slaves and the workers and farmers who saw Civil War policies like the Homestead Act and the creation of land grant colleges as advancing their class interests.

The Supreme Court as the defender of unregulated monopoly/finance capital, 1877–1937

The Supreme Court and the federal judiciary in the aftermath of the Civil War fiercely defended the interests of “big business,” which Marxists defined as monopoly capitalism, against organized farmers, workers, state governments, and the federal government. In the 1880s, the Supreme Court in a series of decisions invalidated the civil rights acts of the Reconstruction era and the 14th Amendment’s protection of citizenship rights from state government policies. States were permitted to ignore the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which banned exclusion and discrimination in public accommodations. That protection would only be restored by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 after a century of de jure segregation.

In 1896, the Plessy v. Ferguson decision gave states the right to establish segregation by law, using as a cover the principle of “separate but equal” under such laws, although it was clear to everyone that the systematic exclusion of African Americans from public schools, public employment, public transportation, and commercial establishments was crudely unequal. The courts also endorsed state laws which denied the overwhelming majority of Black people the right to vote; the convict lease system, a form of slave labor for prisoners; and state “poll taxes,” which primarily discriminated against poor whites (in most places African Americans had been already disenfranchised).

At the same time, the Court in the 1880s took the 14th Amendment’s defense of the rights of “persons” and applied it to business and corporations, declaring state laws regulating business to be unconstitutional. At the time the 14th Amendment was proposed and enacted, everyone understood that the “persons” referred to were the 4 million former slaves, no longer under law, but not yet citizens.

But this was just the beginning. An early modest federal income tax (a surcharge on high incomes) was declared unconstitutional in the Pollock case. It negated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890) by declaring that the federal government and the states could only regulate commerce — not manufacture — under the Constitution. In an industrial society, regulation became a farce.

Decades later, a constitutional amendment gave the federal government the right to levy income taxes, and Congress passed legislation that, to a limited extent, regulated trade and restructured the banking system. However, the Court routinely declared unconstitutional state laws protecting the right of workers to organize unions, providing for the health and safety regulation of workplaces, minimum wages, and the 1916 federal law outlawing child labor.

It was not until the Great Depression of the 1930s, which saw the great upsurge of labor with the Communist Party playing a central role, that the New Deal government enacted the most important labor and social welfare legislation since the abolition of slavery and battled to compel the judiciary to accept these major reforms in the interests of the working class and the whole people.

The Supreme Court and government as the protector and defender of the general welfare, 1937–78

The struggle for major judicial reform went back to the late 19th century. It sought to de-emphasize precedence, the “dead hand” of previous decisions, and make the law respond to social changes and realities, to connect the “facts” as they existed in the present with past decisions under the law. Law professor Roscoe Pound and attorney Louis Brandeis were the champions of this approach to law, called “legal realism.” Brandeis especially popularized the doctrine in leading campaigns against corporate monopolistic price fixing and business corruption of public officials, which earned him the name “the People’s Attorney.”

He also developed a legal brief which incorporated social research (the Brandeis brief) in arguing cases. His fame in the early 20th-century Progressive movement led Woodrow Wilson to appoint him to the Supreme Court, where he joined with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes to represent a minority that supported the regulation of industry, social legislation, and the defense of First Amendment civil liberties. Regarding civil liberties, the minority supported freedom of speech, assembly, and association unless, in Holmes’s language, there was a “clear and present danger” to society, and not just a “dangerous tendency” that certain acts might lead to others, which was the conservative position.

In the 1936 elections, Roosevelt campaigned against the old-guard Court and the “economic royalists” whom they represented, reviving the language of the American revolution in his and the New Deal’s sweeping victory. Roosevelt sought to expand the court for every justice over the age of 70, which would have increased its size to 15 justices.

In the 1936 elections, Roosevelt campaigned against the old-guard Court and the “economic royalists” whom they represented, reviving the language of the American revolution in his and the New Deal’s sweeping victory. Roosevelt sought to expand the court for every justice over the age of 70, which would have increased its size to 15 justices.

Conservatives fought back, wrapping the Court in the Constitution, attacking his court reorganization plan as “court packing.” In the Court fight, conservative Southern Democrats, including many who had worked behind the scenes against the New Deal like senators Tom Connally of Texas and Walter George of Georgia, along with the vice president, John Nance Garner, turned against Roosevelt.

The weakened GOP let the Democrats carry the ball, but it was from this court fight that the informal conservative coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans began to take shape.

Faced with the attack, the Court, which had four Coolidge/Hoover “Business of America is Business” conservatives, three urban liberals, and two moderate conservatives, shifted. In 1936 the Court had voted 6-3 against the New York minimum wage law. But in 1937 the Court upheld by a vote of 5 to 4 a similar Washington State minimum wage law, ruled in favor of the Wagner Act in the Jones and Laughlin Steel case, and upheld the Social Security Act and unemployment insurance. In all these rulings, Owen Roberts and Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes changed their votes to side with Roosevelt.

By the end of 1937, as the old-guard conservatives began to retire, Roosevelt, defeated in the reorganization fight, began to replace them with New Dealers and by the time of the Pearl Harbor attack had forged a New Deal majority.

The new Court moved away from the old doctrines of constitutional original intent associated with the corporate-dominated courts of the post–Civil War era toward a view that the Court must change with changing economic and social conditions. Most of all, the Court retreated from its support for business and its defense of the absolute right of freedom of contract. Instead, a law was to be “presumed constitutional” on questions concerning economic power and government regulation — constitutional regulation came to be seen, as one decision put it, as regulation for the “public good.” Economic freedom was no longer the preferred freedom of the court, and economic activity was no longer local and thus not regulatable.

The court also upheld in the Fair Labor Standards Act minimum wages for all citizens, whereas later it vetoed state minimum wage legislation for women, refused to apply the anti-trust laws to unions, and outlawed the sit-down strike in 1939 (NLRB v. Fansteel Metallurgical Corp.), but in a decision that defended and established peaceful picketing.

At the same time, the Court under New Deal leadership began to develop a new doctrine of preferred freedoms, a doctrine that stressed the need to protect the rights of political dissenters and minorities. In late 1937, the Court declared unconstitutional state laws barring speech and assembly that had been used to convict and imprison Communist Party activists like Angelo Herndon in Georgia, later explicitly defended religious freedom in the case of Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal to swear allegiance to the flag, and revived the clear and present danger criteria to protect free speech and assembly.

In 1938 the Court, for the first time since the end of Reconstruction, enforced some civil rights claims when it contended that the state of Missouri, by not supplying legal education for Black students had violated the separate but equal doctrine of Plessy (Missouri had offered to pay part of their tuition). While the decision didn’t challenge segregation, it pressured Southern states to increase educational programs under segregation for African Americans.

In the Hague case, the Court declared unconstitutional a local Jersey City ordinance against picketing and demonstrations which had been used for mass arrests — subsequently, this was defined to mean peaceful picketing. In U.S. v. Carolene Products (1938), the majority ruled that the court would no longer apply “heightened scrutiny” to economic legislation; however, in a footnote, Harlan Fiske Stone added that the Court was obligated to apply a “more exacting judicial scrutiny” in cases where laws or regulations contradicted the Bill of Rights or adversely affected minorities. The famous “footnote 4” had important implications for Bill of Rights freedoms for dissenters and minorities.

Following the recession of 1937 and the business-conservative counter-attack and backlash of 1938, the New Deal was politically stalemated in Congress and without a clear program. However, by this time, the labor social welfare program was consolidated, at least for the short term. Further, the great fortress of conservative power protected from the electoral process — the Supreme Court — was overthrown.

Democratic President Harry Truman’s appointees set back the Court’s support for civil liberties, especially in the 1950–51 Eugene Dennis case, where the Court upheld the convictions and imprisonment of the leadership of the CPUSA under the 1940 Smith Act. The appointments of Earl Warren as Chief Justice and William Brennan by Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, however, greatly strengthened the Court’s progressive majority at a time when Cold War policies moved Congress and the president to the right.

In the Brown decision (1954), the Court declared school segregation unconstitutional. The Supreme Court also in the Yates and other decisions made illegal some of the worst aspects of state and federal anti-Communist policies, leading the FBI to establish its secret Cointelpro program. In the later Miranda and Gideon decisions the Court limited police power to interrogate and hold suspects without formally charging them and reading them their rights, including their right to legal representation or a court-appointed attorney to represent them. The Court also rejected early challenges to the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965. Although Richard Nixon’s election to the presidency and his appointments moved the Court in a more conservative direction over time, Court decisions in the early 1970s effectively abolished the death penalty in the U.S. and, in Roe v. Wade, legalized abortion.

The empire strikes back: The Court’s long march to the right, 1978–present

Even before Ronald Reagan gained the presidency, the Nixon-influenced Court began to move to the right. In 1976, the court gave states the right to reestablish the death penalty (subsequently the death penalty would be established at the federal level in a more extensive way than at the state level). In 1980, the Supreme Court upheld an amendment to the funding of Medicaid in 1976 which barred the use of Medicaid funds for abortions, a cruel blow to the rights of low-income and poor women.

Over the following four decades, a series of decisions chipped away at civil rights and civil liberties; weakened the regulation of commerce, industry, and finance; and removed restrictions on the use of money in elections. The Court’s conservative majority became more militantly reactionary, destroying earlier compromise decisions brokered by conservatives. Donald Trump, who gained the presidency in large part because of the deeply undemocratic nature of U.S. politics, failed to implement his far-right domestic policies, which both large numbers of Americans and people throughout the world saw as “neofascism.” However, his “success” in appointing three Supreme Court judges is now his “legacy,” in that they are doing what he failed to accomplish.

What we can and should do now

First, we must understand that a large majority of the people oppose these decisions, just as in 1857 and 1936 a large majority of the people opposed the Supreme Court’s pro-slavery Dred Scott decision and its decisions declaring New Deal regulatory and social legislation unconstitutional. The Republican Party mobilized opposition to the Dred Scott decision to win the 1858 congressional elections. More than 70 years later, the Democratic Party mobilized opposition to the conservative Court’s decisions to propel Roosevelt to an overwhelming victory in the 1936 national elections.

The same kind of united opposition must be organized now. We must point out that the present Court has set the nation back and may continue to block progress regarding immediate issues such as inflation, health care, or the cost of energy and transportation. Were the government to attempt, for example, to establish price controls, create a national public health system, and expand public transportation, the Court would not be on the people’s side.

The trade union movement, all civil rights and women’s rights organizations, and all environmental organizations must mobilize supporters and communities throughout the nation to vote against the Republican senators and congresspeople who over decades have created this judiciary. Such an electoral victory is necessary but not in itself sufficient. Many today are calling for an expansion of the Court. Congress and the president have the power to do that, since the number 9 is not in the Constitution. We should begin to think about a larger expansion of the federal judiciary itself. Since the 1980s, the conservative Federalist Society has advanced the doctrine of original intent as a cover to restore Court rulings opposing federal regulation of business and social welfare legislation. A government committed to restoring what the Court had represented in the New Deal–Great Society era should actively appoint attorneys who support those positions.

Finally, the question of judicial review itself could be formally ended by Congress and the president. As was contended earlier, it is not a part of the Constitution, and there is no evidence that the Constitutional Convention intended it to be established. The Court has acted to strike down and take away from the people major social protections and rights. As such its power of judicial review can and should be taken away from it.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: Supreme Court building, Joe Ravi, (CC BY-SA 3.0); Suffragettes picketing White House, Wikimedia (public domain); Civil War Union “well-regulated militia,” Mathew Brady, Wikipedia (public domain); Dred Scott, Wikipedia (public domain); Child labor, 1908, Kelly Short (public domain); Roosevelt, pingnews.com (public domain); Flint sit-down strike, 1937, Wikimedia (public domain); African American School, 1916, pingnews.com (public domain); Congress sold, Public Citizen (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Abortion rights rally at Supreme Court, Adam Fagen (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Comments

[ad_2]

Source link