50 Black sailors were convicted of mutiny for striking after a deadly WWII explosion. Will their names ever be cleared?

[ad_1]

When handling bombs, Freddie Meeks would often worry. The young Black sailor was assigned to load munitions onto ships during World War II in Contra Costa County. Meeks imagined a chain-reaction tragedy, bomb detonating bomb, until everyone there had been blown into oblivion.

Late on the evening of July 17, 1944, such a tragedy killed 320 people at Port Chicago Naval Magazine in Concord. Black sailors accounted for 202 of the victims.

White officers and enlisted men who survived were sent home for 30 days leave; Black sailors were told to get back to work loading bombs and ammunition for fighting in the Pacific. Fifty who refused to work in such perilous conditions, including Meeks, were later convicted of mutiny and imprisoned for a year and a half. The treatment of the Port Chicago 50, as they came to be known, provoked backlash at the time and accelerated the desegregation of the military.

But nearly 80 years later, efforts continue to clear their names formally.

Freddie Meeks’ uniform at the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum.

Brittany Hosea-Small / Special to The ChronicleU.S. Reps. Mark DeSaulnier, D-Concord, and Barbara Lee, D-Oakland, are pushing once again to exonerate the men. They passed a measure through the House that, if approved by the Senate, would direct Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro to exonerate the 50, who have all died, and restore their service records.

There’s no guarantee the Senate will pass the measure. There might be every reason to suspect it won’t.

DeSaulnier said he has advanced the same measure to the Senate three times in recent years without passage. DeSaulnier’s predecessor, George Miller, campaigned decades for exoneration before his 2015 retirement.

DeSaulnier said fears of legal liability — such as reparations for the families of the 50 — might be a factor in the recalcitrance. “We’ve had to say over and over again, ‘This isn’t about money,’” the congressman told The Chronicle. “This is about fixing a historical wrong.”

The measure to exonerate the 50 is tucked into the budget for the U.S. Department of Defense, as it has been in the past. The bill is expected to be taken up in the Senate sometime this fall.

Shrapnel from the explosion at Port Chicago is displayed at the Vallejo Naval and Historic Museum.

Gabrielle Lurie/The ChronicleThis year’s efforts come two months after the release of a 500-page report from California’s reparations task force, which details the state’s racist past. Though the state joined the Union as anti-slavery, it welcomed white enslavers from the South who came during the Gold Rush in 1850. Two years later, conservative estimates say, there were 500 to 1,500 enslaved African Americans in California.

The years of Jim Crow were brutal with the spread of the Ku Klux Klan and “sundown” towns, where white residents sought to keep others out of their borders with ordinances and threats of violence.

The story of the Port Chicago 50 is, advocates say, another stain on the Bay Area, the state and the U.S.

“Hopefully, at some point, it will be full exoneration,” said Meeks’ son, Daryl Meeks.

His father’s story, revealed in historic and new interviews, newspaper archives and government records, shows the horrors the Port Chicago 50 endured both during their service and throughout their lives.

‘No safety’

Freddie Meeks, a 24-year-old who had grown up in Memphis, digging ditches to help his widowed mother, had just finished his shift that night stacking munitions onto the E.A. Bryan, one of two naval ships docked near the munitions facility.

As he walked toward the barracks, he and other men still working sang “Anchors Aweigh,” the Navy song: “Anchors aweigh, my boys, anchors aweigh,” they sang. “Farewell to foreign shores, we sail at break of day, of day.”

Before long, the blasts came.

The force could be felt in Nevada and all but vaporized a pier on Suisun Bay. It reduced ships to splintered memories, men into aching voids in families back home.

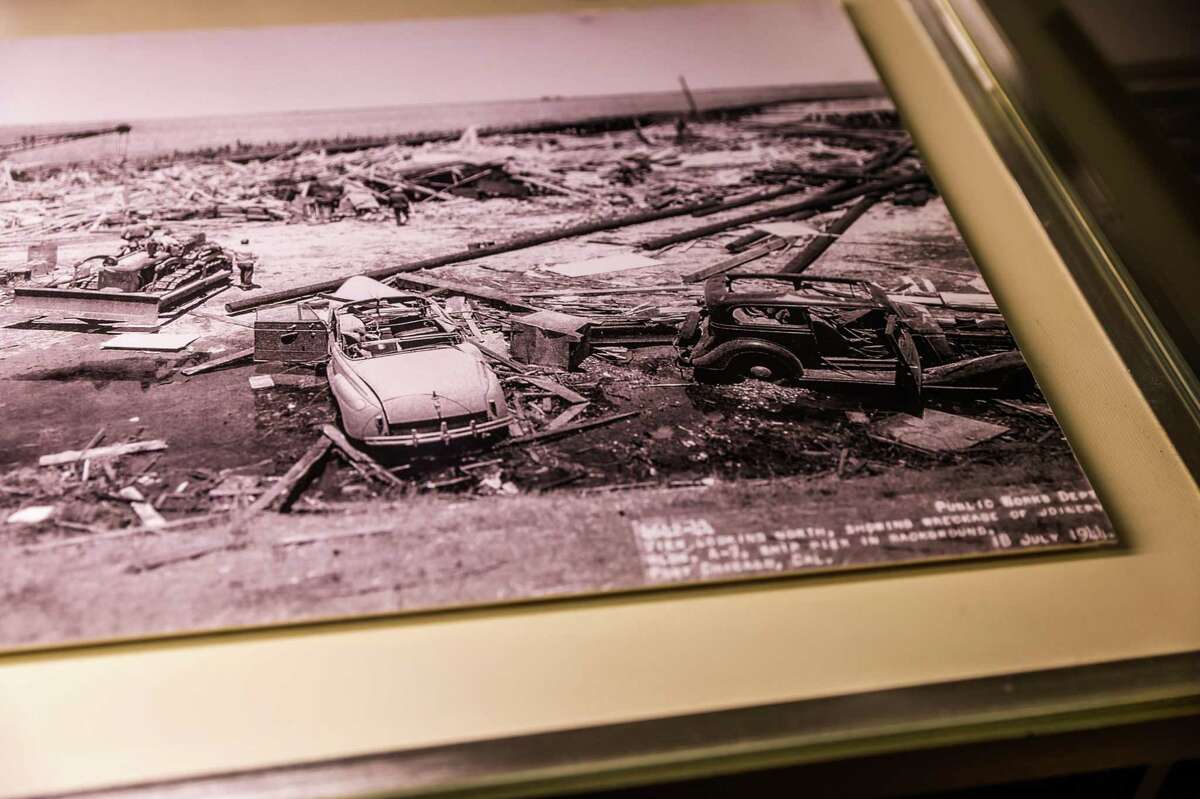

A photograph of the aftermath of the explosion at Port Chicago is displayed at the Vallejo Naval and Historic Museum.

Gabrielle Lurie/The ChronicleThe precise cause would never be determined. But Meeks figured a bomb went off in one of the train cars that brought in the bombs and ammunition.

“There was no safety,” Meeks told journalist and scholar Robert L. Allen in 1980, when Meeks was 60. “There was no training.”

Meeks and the other Black sailors spent 22 days sorting body parts and debris. When the segregated barracks were moved to Mare Island in Vallejo, where bombs and ammunition were also loaded, the men knew they would be asked to get back to work filling ships. Only Black sailors handled munitions at both sites.

Some sat up talking the night before they expected to be asked to return to loading duties. As Steve Sheinkin detailed in his 2017 book, “The Port Chicago 50,” the Navy would later call this a secret meeting to plot a mutiny while the sailors maintained it was a conversation about the grim fate that could await them.\

The next day, a white officer marched a group of sailors toward a ship.

Suddenly the sailors stopped, some clumsily bumping into each other.

The officer asked the men if they were refusing to work. They confirmed that they were, and he reported them to a superior who tried to persuade the men.

How, the white man asked, was this any different than the danger men faced in foxholes?

Standing there, some of the sailors had tears in their eyes, considering the question.

You can fight back in foxholes, one of the sailors called out, but you can’t fight back here.

A framed photo believed to include Freddie Meeks and his crew from the Port Chicago Naval Magazine at the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum.

Brittany Hosea-Small / Special to The ChronicleIn the coming hours, a total of 258 sailors told officers that they wouldn’t handle ammunition. Meeks told a superior that he would go to the front, but he was terrified to continue handling bombs. All but 50 men would decide to go back to work after an admiral threatened to recommend they be tried for mutiny and put to death by firing squad.

The 50 were put on trial for their lives within weeks.

During court martial proceedings on Treasure Island, they were convicted and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. They remained incarcerated until 1946, when prodding by figures including Thurgood Marshall, then the chief legal counsel for the NAACP, helped lead to their shocking early release and sudden reassignments to Navy outposts and ships across the world.

Silence

Meeks didn’t talk about it.

He worried what people would think, or do, if they found out he was one of the Port Chicago 50. He had to try to skirt questions about convictions on job applications. He found positions in a tire factory and as a butler before a long stint working for Los Angeles County in a mechanic shop.

When Daryl Meeks was a boy, he would press his dad for stories from the war, like kids he had seen on TV. The father didn’t leave the son wanting, but the stories he told took place after his release from prison, when he was on a ship in the Pacific.

Daryl Meeks hadn’t even heard of Port Chicago, let alone his father’s role, until one day in August 1980.

Daryl Meeks, 64, in front of a cotton tree that his father planted at home in Los Angeles. Meeks learned in his 20s that Freddie Meeks was one of the Port Chicago 50.

Philip Cheung/Special to The ChronicleHe stopped by his parents’ home on his way to work in Los Angeles, where the family had lived before and after the war. Daryl Meeks found his father in tears.

“I was in my early 20s and I had never seen my father cry — ever,” Daryl Meeks told The Chronicle.

His father was in the middle of speaking with Allen, the journalist who would write the 1989 book, “The Port Chicago Mutiny.” Freddie Meeks’ wife, Eleanor, had suggested he skip the interview, but he had decided he needed to tell the story.

“When you look back on it now,” Allen said that day, “how do you feel about it?”

“You feel kind of like you got a raw deal on it,” said Freddie Meeks, who had been found guilty of mutiny on his 25th birthday. “The way they hound us every day, treated us, and then they talk about their own prisoners of war and how the other countries treated them.”

He said he and others had long been bitter because of the racism at the heart of their treatment.

Even the Navy acknowledged their assignment of loading bombs and ammunition was motivated by racism. “The routine assignment of Afro-Americans to manual labor was clearly motivated by race and premised upon the mistaken notion that they were intellectually inferior and thus incapable of meeting the same standards as their white counterparts,” a 1994 Navy report examining the case said.

Freddie Meeks’ last name and first initial are in the waistband of his work uniform pant at the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum. The items were donated in 2021 by Meeks’ daughter, Cheryl Elaine Jackson.

Brittany Hosea-Small/Special to The ChronicleStill, the review didn’t recommend exoneration.

Exonerations for military convictions are even rarer than in civilian court. Since 2003, six people were cleared of crimes they were convicted of in the military, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. That’s compared to hundreds in the same time period in civilian courts.

But what Port Chicago 50 supporters are asking for isn’t unprecedented.

In 2008, the Army formally exonerated 28 Black soldiers who had been wrongfully convicted in the lynching of an Italian prisoner of war in 1944. Their exoneration came after it emerged that the Army had hidden from the defense evidence that a white military police officer was suspected in the murder.

‘Not around to see it’

As his health was failing in the late 1990s, Freddie Meeks decided to seek a pardon. This was, he would say, to keep the memory alive and expose what happened.

A pardon is forgiveness for a crime, not exoneration, which would be a statement of innocence. It was a symbolic gesture, as pardons don’t clear a person’s record. But a pardon was what seemed attainable. In the application, Meeks’ lawyers said the Navy appeared incapable of a fair review of the case that would lead to exonerations.

“(Seaman Second-Class) Meeks has suffered in silence from this unjust conviction long enough,” the attorneys wrote in the May 1999 pardon application, archived by the National Park Service, which has a memorial at the site of the Port Chicago disaster on Navy property. “He served his country honorably in a time of war despite the Navy’s complete neglect of both his worth as a human being and the benefits of his contribution because S2c Freddie Meeks is Black.”

President Bill Clinton granted the pardon for Meeks at Christmas in 1999.

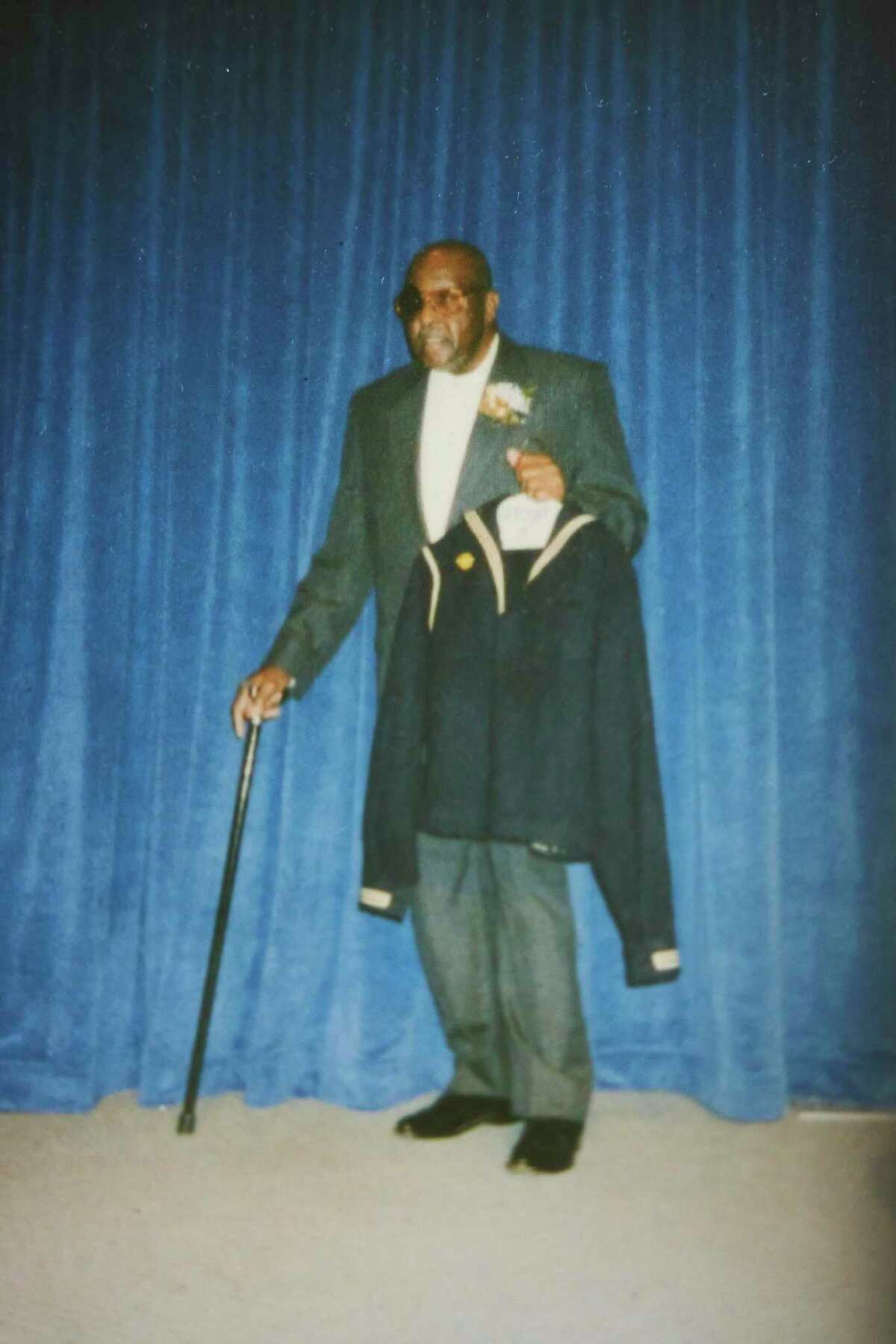

Freddie Meeks shows his Navy uniform from World War II.

Provided by Meeks family“I know God was keeping me here for something to see,” Meeks told reporters. “’But I am sorry so many of the others are not around to see it.”

Meeks was 80. It had been 55 years, each made harder in some way by his experience. Only one other of the 50 men was known to be alive.

“It was really late for my father,” said Daryl Meeks, 64, whose father died in 2003 of complications from diabetes. “He was thankful for what President Clinton did. It didn’t change what he had gone through for all those years.”

A formal exoneration from the Navy wouldn’t either, of course, but it would be a formal statement that the men weren’t mutineers.

“It is our duty,” Congresswoman Lee said in a statement, “to call out this racial discrimination and ensure history recognizes them as heroes, not criminals.”

Sharon McGriff-Payne, a Vallejo historian and author who focuses on the area’s deep African-American history, is resolved to tell the story to honor the men.

Vallejo historian and author Sharon McGriff-Payne sits at the memorial she lobbied for to honor the Port Chicago 50.

Gabrielle Lurie/The ChronicleShe lobbied the city to honor the Port Chicago 50 and the Vallejo site of their historic work stoppage, as she refers to what the Navy calls a mutiny. The precise spot where the men stopped marching is believed to be on Ryder Street, a short, dead-end industrial stretch off the Napa River.

Beneath a towering redwood there, McGriff-Payne sat Tuesday morning on a bench in front of the memorial the city installed in 2019. McGriff-Payne grew up hearing about the disaster from her parents: Her father was assigned with other Black men to load bombs onto ships on Mare Island during the war and trained with some of the men who would be convicted of mutiny.

The knee-high marker, encircled with 50 black stones, is easy to miss, just across a fence from the city wastewater treatment plant. But there’s a bench where people can sit and reflect, and the redwood gives shade. And anyone who comes here can read the story of the Port Chicago 50 — the way their supporters would have it told.

“This memorial is dedicated to the 50 African American sailors who in August 1944 courageously refused to work under unsafe and dangerous conditions …”

Joshua Sharpe is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: joshua.sharpe@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @joshuawsharpe

[ad_2]

Source link