‘Everything I do is saying Black lives matter’: how artist Amy Sherald defined an era | Art

[ad_1]

Amy Sherald just needs 10 minutes. For the artist, a small period of alone time each morning is the goal, but it’s easier said than done. “I try to wake up before everybody and have 10 minutes of quiet,” says Sherald, who lives with her partner, Kevin Pemberton, and her mother. “Once [my mom] hears me up, she’s like: ‘Hello! It’s Amy and mom time,’” Sherald says with a laugh.

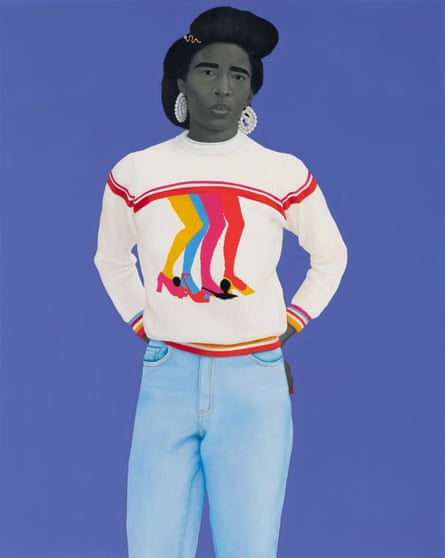

Quiet time will come soon enough. But right now, the 49-year-old artist is busy packing for a month-long trip ahead of her first solo exhibition in Europe, The World We Make. The show is “a natural next step”, she says, employing her signature use of grisaille (“[I just say] I paint in black and white,” she jokes when I ask how to pronounce the French term). She uses the greyish tone in place of Black skin tones as a means of challenging marginalisation of her work, and to create language around her identity – in her words “bringing a kind of poetry to Black figuration”.

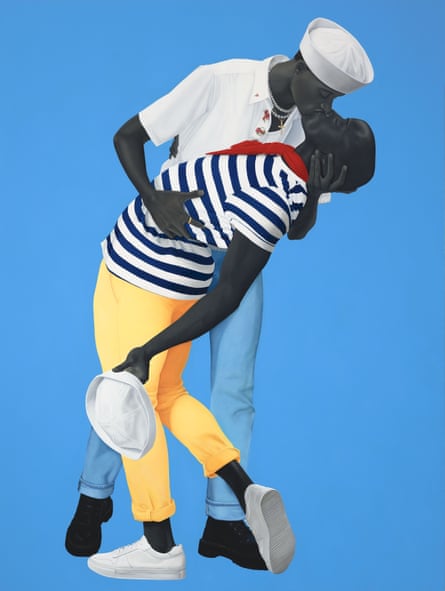

The unwavering eye contact between painted subject and viewer has been maintained in Sherald’s new exhibition, along with the colourful, curated wardrobe for her subjects. But, in addition to the everyday people featured in her work, The World We Make also alludes to historic images, reinserting Black people into iconic moments in the western canon where our impact is understated. Her reinterpretation of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day in Times Square photo features a Black homosexual couple, just one example of the artist’s reconstruction.

Although the paintings are done, a “fried” Sherald acknowledges, there are still final travel arrangements and preparations for the show to be made. When we meet at her chic New Jersey home, Sherald, sporting jeans and a grey crew neck, is relaxed and happy (her default mood, she says) as we sit on white, fluffy stools round her dining room table.

“I’m always pretty much making the best of everything,” she says. “Because there’s the opposite of that [and] it’s unproductive.” The Columbus, Georgia-born artist has had an explosive past four years, ever since she received widespread recognition for her 2018 portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama. “She’s an icon,” says Sherald. “She represents for me and a lot of women what 21st-century womanhood looks like.”

Since winning the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever portrait competition in 2016 and painting Obama, Sherald’s public profile has ballooned. There was a cameo appearance in the TV reboot of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It, and Sherald was dressed alongside eight other culture-makers by fashion brand Thom Browne, described by GQ magazine as the “coolest clique in fashion”.

While some mistakenly cast her numerous accolades as shotgun successes, a mild frustration Sherald experienced after the Obama portrait’s unveiling, she has built her successes on a solid foundation: a decades-long art career with multiple exhibitions, apprenticeships and a master of fine arts in painting. “I think it’s really important that people understand that this stuff doesn’t happen overnight,” says Sherald.

Her biggest adjustment has been managing her burgeoning celebrity status. “I‘ve learned to have a public persona,” Sherald says. “It’s not that it’s inauthentic. But I had to learn how to be in public.” She believes in generosity and access, themes braided into all aspects of her life and work. So, if an autograph needed to be signed, she signed it. An admirer wanted a hug? An embrace was given. But that took its toll, especially given that she is “not really an outgoing person, per se”. Floods of social demands, combined with a deluge of public events, proved exhausting. “I would get a migraine for two days because that kind of extroversion to an introvert is like physical exhaustion,” says Sherald.

Now, almost three years after the aforementioned unveiling, Sherald has a greater appreciation for boundaries and recharging: “You have to learn what your limits are and then learn how to say no.” Certain presences in her life do help the artist recharge. Three members of Sherald’s support team greeted me when I first walked through the door: her dogs George, Weezie and August Wilson. “They should get paid as therapists,” Sherald jokes, as the trio play-fight near her feet.

Despite all the changes to her life, Sherald still makes herself available to younger artists in need of a mentor who can shed light on the inner workings of the art world and market. Her easy manner may be partly due to being raised in the south of the US. Or maybe it’s her avid embrace of non-New York City living, a puncturing of shallow requirements for being a “real” artist. Or it might be that Sherald’s just a “giver”, a role she says comes naturally but also one she’s been placed into during various family and personal emergencies.

Sherald’s father died of Parkinson’s disease when she was 28. Her brother died from lung cancer at 36. She has navigated her own serious health problems, receiving a heart transplant at 39. “I just really understand that life is short and that waking up today [is] the best thing that could ever happen,” she says.

No aspect of Sherald, her personhood nor her artwork, is concerned with ornamentation and superficiality. She is direct and sincere, drawing boundaries on what she is willing to share publicly, but never hiding. Like her work, she is an embrace of Black inner life, of honesty beyond observations. It’s a negotiation of the public versus the private and what deserves space in the narratives we showcase to the world.

Black people are often laid bare for white education, curiosity and betterment. The summer of 2020, with racial justice protests pollinating across America, proved to be no different. The pain and trauma of Black people was shared widely for white people to observe their own capacity for violence. But Sherald’s work remains an invitation to go beyond the simple observation of Blackness attached to a legacy of violence and oppression, as with her lauded posthumous portrait of Breonna Taylor, which appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair in September 2020. “[I] kind of feel like she’s with me every day,” Sherald says of Taylor.

On 13 March 2020, emergency room technician Taylor, 26, was shot and killed by Louisville police officers who forced entry into her apartment as she slept. Crafting a portrait of Taylor that exists outside the brutal and cruel way her life ended was a heavy responsibility. “I wish that this momma could have her daughter back because it didn’t have to happen”, says Sherald about Taylor’s mother, Tamika Palmer.

But Sherald delivered something exalting, placing Taylor in a turquoise dress instead of her EMT uniform, her left hand gently placed on her hip while an engagement ring she never received from her boyfriend sits on her right. Taylor’s portrait, like much of Sherald’s work, was critically acclaimed, described by Forbes as the “most important painting of the 21st century”.

Sherald is immunocompromised and couldn’t participate in the 2020 racial justice protests, so the portrait of Taylor was her “opportunity to really have a personal reaction and connection to that moment, offering something that could codify that moment, historically and in context”. (Sherald has also donated $1m to establish two grant programmes in Taylor’s name.)

Especially after the Obama portrait, Sherald still sometimes encounters questions about her use of grey to depict Black skin. She invites the questions as part of the dialogue and questioning that art should produce. But Sherald draws a hard line at the intrusion of whiteness in her work, especially questions about if and when she’ll paint white people. “It’s a lack of awareness, even to look at my work, and then think about yourself,” she says. “It’s the whitest thing that you could do. Everything that I do is saying that Black lives matter. For me, Black lives matter historically within the American art canon, [and] Black lives matter in our history.”

Still, Sherald doesn’t fully identify her work as being “revolutionary”, admitting she recoils at the term (“That’s just me and my own self-conscious weirdness”). The dismissal isn’t from a lack of confidence, but rather it’s a term she feels should be tied to politicians and activists, such as Stacey Abrams and Angela Davis. Even a complete claim about the impact her art has had or her position as one of the most significant contemporary artists feels off to her. “If it’s written when I’m dead, but that’s the way that my life patterns itself out, that’s fine … But I think I’ve always just seen myself as myself and my contribution as the work. And it sits in the world and does its thing.”

For now, questions of legacy and remembrance are important but the work remains the priority. It is what has kept her primed and ready for the abundance that has come her way. “I stayed focused on making the work. And the opportunity found me.”

Amy Sherald: The World We Make is at Hauser & Wirth, London, from 12 October to 23 December.

[ad_2]

Source link