Structural interventions that affect racial inequities and their impact on population health outcomes: a systematic review | BMC Public Health

[ad_1]

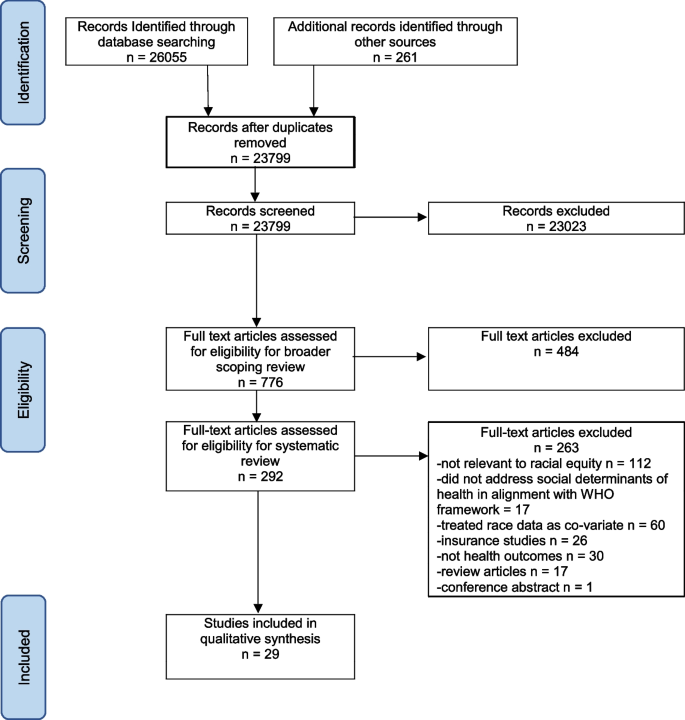

Database searching for the broader, related scoping review retrieved 24,311 records and citation tracking retrieved an additional 261, for a total of 26,055 records. After removing duplicates, 23,799 records were screened by title and abstract, resulting in 776 records for full text review for inclusion in the broader scoping review. Of those 776 records, 292 articles were screened for health outcomes by race for eligibility for this systematic review, resulting in 29 included articles. Studies excluded at this stage are listed in Additional file 2. See Fig. 2 for a PRISMA flow chart illustrating the article search and selection process.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. Of the 29 included studies, 28 were natural or quasi-experiments and one was a randomized controlled trial. Most were conducted in the USA [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63, 67], along with one study in Canada [65] and two in Australia [64, 66]. Studies were published from 2008 to 2021, with data collection periods starting as early as 1927.

Interventions were targeted at several major policy domains, including financial (n = 10) [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], nutrition safeguards (n = 5) [49,50,51,52,53], immigration (n = 7) [54,55,56,57,58,59,60], family and reproductive rights (n = 3) [61,62,63], policies for Indigenous populations (n = 3) [64,65,66] and environment (n = 1) [67]. Only the interventions in the immigration policy domain and those related to Indigenous populations were explicitly designed to affect racial inequities. All other interventions were targeted to low-income or general populations, but reported outcomes stratified by race.

Twelve studies were specifically designed to evaluate health outcomes for racial or ethnic populations [43, 54,55,56,57,58, 60, 64,65,66,67]. The remaining 17 studies evaluated racial and/or ethnic differences as a secondary objective or as part of a stratified analysis [39,40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, 61,62,63], including all except one study of financial interventions [43], all studies of nutrition safeguards and all studies of family and reproductive rights policy interventions. Studies included White, Black, Latinx, Hispanic, Asian and Indigenous populations. Approximately one-third (n = 11) [39, 43, 45, 52,53,54, 57, 58, 62, 64, 66] of the included studies compared outcomes before and after policy implementation, while the remaining (n = 18) [40,41,42, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 55, 56, 59,60,61, 63, 65, 67] compared outcomes for similar populations not subject to the policy or differing levels of policy implementation.

Quality of included studies

Most studies were rated as being of moderate methodological quality (n = 23), with three each rated as high and low quality. Quality appraisal results for the 28 quasi-experimental studies are included in Table 2 and for the randomized controlled trial in Table 3.

All quasi-experimental studies were assessed for a temporal relationship between variables, to assess validity of a causal relationship. All were rated as valid since policy implementation clearly preceded the measured outcomes. Most quasi-experimental studies (n = 25) [39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 47,48,49,50,51,52, 54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, 65, 67] performed secondary analyses on existing datasets, so the completeness of follow-up was rated as not applicable, lowering the possible total score for these studies. The single included randomized controlled trial was rated as moderate, with limitations for blinding of participants and outcome assessors, and unclear completeness of follow-up [46].

Study findings

Findings from included studies are grouped by intervention policy domain with descriptions for how the interventions align with the WHO CSDH framework (Fig. 1). Study findings are reported for each policy domain.

Financial policies

Nine quasi-experimental studies [39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 47, 48] and the one RCT [46] explored interventions related to financial policy in the USA. Interventions aligned with macroeconomic policies in the WHO CSDH framework [33], such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for low-to-moderate-wage earners [39, 41, 42, 45, 47], government expenditure on non-healthcare services [44], and/or minimum wage laws [43, 48]. Other interventions aligned with social protection public policies as a determinant of health, such as Old Age Assistance [40], and the New Jersey Family Development Program [46].

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) reduces personal income tax liability for low-to-moderate workers in the USA, with amounts varying across states and increasing with the number of children in the household [68]. Two studies found no effect of different levels of EITC on adult health behaviours such as smoking and health-related outcomes [39, 41]. Financial stress in lower-income populations has been associated with smoking behaviours [69,70,71]. Averett and Wang found no statistically significant change in smoking status for Black or Hispanic mothers due to EITC expansion [39], while Braga et al found no statistically significant effect on self-reported overall health, obesity, high blood pressure, functional limitations, emotional problems during adulthood for Black, Hispanic or other racialized adults related to differing levels of EITC received during childhood [41]. The remaining three EITC studies examined intervention effects on birth outcomes with mixed results [42, 45, 47]. Bruckner et al found no significant difference in the odds of very low birthweight between Black and White women receiving the EITC, except in the case of Black women who received the EITC within 2 months prior to delivery, who had increased odds of very low birthweight [42]. Hoynes et al found an association between EITC expansion to a higher maximum available credit amount and reduced incidence of very low birth weight for Black women (0.73%, p < 0.01) [45]. Komro et al found that higher levels of EITC were associated with statistically significant improvements in evaluated birth outcomes, such as birth weight and gestational age, for both Black and White women, but not for Hispanic women [47].

One study reported the effects of government expenditure on non-health services on infant mortality [44]. Expenditures included spending on social services, housing, education and environment. Goldstein et al found no statistically significant difference in the association between government spending and infant mortality for infants born to Black, Hispanic, Asian or White mothers [44].

Two studies reported positive effects of higher minimum wage on health outcomes in the USA [43, 48]. Cloud et al evaluated the incidence of HIV cases in Black heterosexual individuals across Metropolitan Statistical Areas with different minimum wage levels. It was found that Metropolitan Statistical Areas with $1.00 higher minimum wage had 27.12% (95% CI 18.06, 35.18) lower incidence of HIV in this population [43]. Rosenquist et al examined infant mortality for Black and White women across States with different minimum wage levels over three decades. They found that the odds of infant mortality decreased for Black women when minimum wage was higher (adjusted OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.68, 0.94), or had seen a larger increase (adjusted OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82, 0.96) [48].

The USA’s Old Age Assistance (OAA) program expanded in 1935 under the Social Security Act to provide financial benefits to seniors [40]. Balan-Cohen found that mortality due to preventable, behavioural or cardiovascular causes was reduced for Black (12%) and White (17%) OAA recipients in non-Southern states, but the statistical difference between groups was not evaluated [40].

Jagannathan et al found mixed results in an RCT to examine the mental health effects of the New Jersey Family Development Program (FDP) welfare reform, which imposed stricter rules for low-income mothers by denying additional cash benefits to mothers of children already receiving benefits, adding work/training requirements and rapid withholding of benefits for program non-compliance [46]. It was found that Black women subject to FDP reform had decreased incidence of clinically diagnosed anxiety disorders (−15.3%, p < 0.05) and clinically diagnosed depressive disorders (−2.1%, p < 0.05) compared to Black women who were not subject to the reform [46]. Hispanic women subject to FDP reform had increased incidence of clinically diagnosed depressive disorders (68%, p < 0.05) compared to Hispanic women who were not subject to the reform [46].

Nutrition safeguards

Five studies evaluated interventions to improve access to nutritious food in the USA. Within the WHO CSDH framework [33], these public policies impact socioeconomic position in terms of income and gender, to affect material circumstances in terms of food security (Fig. 1). Two studies evaluated the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP) [50, 51], two studies evaluated the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) [49, 53], and one study evaluated the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) [52].

SNAP, the USA’s largest federal nutritional assistance program that provides food purchasing cards for eligible low-income individuals and families [72], was evaluated by two studies that found mixed results. Conrad et al compared age-adjusted mortality for SNAP participants to eligible non-participants of the same race or ethnicity and found a significantly higher risk of mortality from all causes in Black, Hispanic and White SNAP participants and higher risk of mortality due to diabetes for Black SNAP participants compared to eligible non-participants [51]. Authors suggest that participants face greater hardships than eligible non-participants and are therefore less likely to access medical care [51]. Booshehri et al evaluated SNAP by comparing prevalence of diet-related morbidities, such as cardiovascular conditions, before and after changes to SNAP enrollment requirements at age 60 [50]. The analysis applies specifically to individuals aged 56–64 who itemized deductions on their tax return and met SNAP eligibility upon reaching age 60 [50]. The reduction in prevalence of hypertension between ages 56–59 and 60–64 was greater for Black populations than Hispanic or White, and the reduction in prevalence of angina and stroke was greater for Hispanic populations than Black or White [50].

Two studies evaluated Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits [49, 53], which provide federal grants to states to provide food, health care referrals and nutrition education to at-risk pregnant women and children up to age 5 [73]. Arons et al found no significant difference in measures of socioemotional development for Black children who received WIC, compared to children of all races who receive WIC [49]. Kong et al investigated diet quality of mothers and children following changes to WIC to provide more whole grains, fruits, vegetables and fewer saturated fats and found no significant change in diet quality for mothers [53]. Black children had an increase in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and Hispanic children had improved diet quality and reduced saturated fat intake [53].

Jia et al evaluated diet quality in children following changes to the USA’s National School Lunch Program to increase the amount and variety of fruits and vegetables offered, restrict grains to whole grains and restrict sugar-sweetened beverages to non-fat milk only [52]. It was found that Black students increased their overall fruit and vegetable intake, while Hispanic students reduced their weekday fruit and vegetable intake [52].

Immigration

Eight studies evaluated the effect of immigration-related policies on Hispanic/Latinx populations in the USA (Table 1). Six studies evaluated the effects of anti-immigration on health or other health outcomes [54, 56,57,58,59], and two studies evaluated the effect of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy [55, 60]. In alignment with the WHO CSDH framework [33], each of these policies affect governance and influence one’s socioeconomic position based on race and/or ethnicity (Fig. 1).

The six studies that examined anti-immigration policies found that anti-immigrant social climates and more aggressive immigration law enforcement negatively affected Hispanic and Latinx populations [54, 56,57,58,59]. Of the studies evaluating the effect of anti-immigration policies on mental and physical health outcomes for Hispanic and Latinx populations, Bruzelius et al did not find a significant change in Latinx mental health after enactment of national policies that led to increased immigration arrests [54]. The study by Hatzenbuehler et al found that Latinx people in states with more exclusionary immigration policies reported more frequent poor mental health days [54, 56]. In a survey of Latinx adults across different American states, Vargas et al found a relationship between punitive anti-immigration policies and a decreased likelihood of reporting overall health as optimal [59]. Torche and Sirois specifically examined birthweight of infants born to immigrant Latina mothers before and after Arizona’s Senate Bill SB1070, which increased immigration policy enforcement [58]. A statistically significant decline in birthweight was found for infants born in the latter half of 2010, whose mothers were exposed to the passage of the law during their pregnancies [58]. Potochnik et al evaluated the effect of Federal 287(g) program, which enabled increasingly aggressive immigration law enforcement, and found increased food insecurity for Mexican non-citizen households with children [57].

Two studies evaluated the health effects of DACA [55, 60], a program that protected young immigrants who were brought to the USA as children from deportation [74]. Hamilton et al found significant improvements in birth outcomes for infants born to DACA-eligible mothers [55]. Venkataramani et al found that implementation of DACA was associated with significant reductions in psychological distress for those who were eligible for the program [60].

Family and reproductive policies

Three studies examined the effects of policies for reproductive rights and paid family leave in the USA using quasi-experimental designs [61,62,63]. These health and social protection policies align with the structural level of the WHO CSDH framework [33], affecting socioeconomic position in terms of gender and income (Fig. 1).

Coles et al and Sudhinaraset et al found negative health effects of restrictive abortion policies by comparing health outcomes in states with more restrictive or less restrictive abortion policies [61, 63]. In states with restricted Medicaid funding for abortions, Black minors had higher rates of unplanned births than in states without such restrictions, while there was no statistically significant difference for White or Hispanic minors [61]. In less restrictive states, Black women had a lower risk of low birth weight than in more restrictive states [63].

In evaluating the effect of parental leave policy, Hamad et al found that a 6-week paid parental leave was not sufficient to improve breastfeeding outcomes for Black mothers, who were less likely than White mothers to report breastfeeding at 12-months post-partum, while Hispanic mothers who received 6-week paid parental leave were more likely to report exclusive breastfeeding at 6-months postpartum [62].

Policies for indigenous populations

Three studies examined policies designed for Indigenous populations [64,65,66]. Two studies evaluated policies designed to improve living conditions for Indigenous populations in Australia through Indigenous Land and Sea Management Programs (ILSMPs) and Alcohol Management Programs (AMPs) [64, 66], while one study evaluated the generational effect of Canada’s residential school system [65]. The ILSMPs and AMPs align with governance, social policies and cultural values as structural determinants in the WHO CSDH framework [33], impacting socioeconomic position in terms of race, to affect material and health outcomes (Fig. 1). Relevant health outcomes for Indigenous populations are often more holistic and tied to the land on which they reside [75, 76]. The forced relocation and cultural erasure as a result of Canada’s residential school system affected multiple structural determinants based on race, with profound negative effects on material circumstances, behaviours, biological and psychosocial outcomes [77] [cite].

In Australia, AMPs have been used by governments since a 2001 inquiry into domestic violence, injury and deaths that found that historical and ongoing colonialism created conditions that put Indigenous communities at higher risk for alcohol-related harms. Under the AMP, alcohol availability is highly regulated and illicit possession or consumption were strictly penalized [64]. The effects of AMPs were mixed, and while community members reported less violence and increased feelings of safety, they also reported that there was more substance use and law enforcement [64]. Also in Australia, the federal government implemented ILSMPs, which seek to encourage Indigenous land management through creating employment and economic opportunities in land and sea management activities [66]. Implementation of ILSMPs had several positive effects on community members, with the majority reporting satisfaction for the health of the land, their legal right to the land and business ownership, and improvements to information and communications technology access [66].

Feir investigated traditional Western health outcomes for First Nations, Métis and Inuit children whose mothers attended residential schools, and found they had a higher average BMI than for First Nations, Métis and Inuit children whose mothers did not attend residential schools [65]. Educational outcomes were also reported, including increased suspensions, expulsions and worse school experiences for children whose mothers attended residential schools [65].

Environmental

One study evaluated the effects of an environmental policy on health outcome inequities [67]. Furzer and Miloucheva analyzed the effect of Clean Air Act regulations in the USA [67]. In alignment with the WHO CSDH framework [33], the study describes how the Clean Air Act affects public policies in terms of race to impact biological outcomes (Fig. 1). Furzer and Miloucheva found that air pollution limits were less likely to be attained in counties with higher proportions of Black or racialized residents, resulting in 6.8–18% more COVID-19 deaths in these populations than in regions that maintained air pollution limits [67].

[ad_2]

Source link