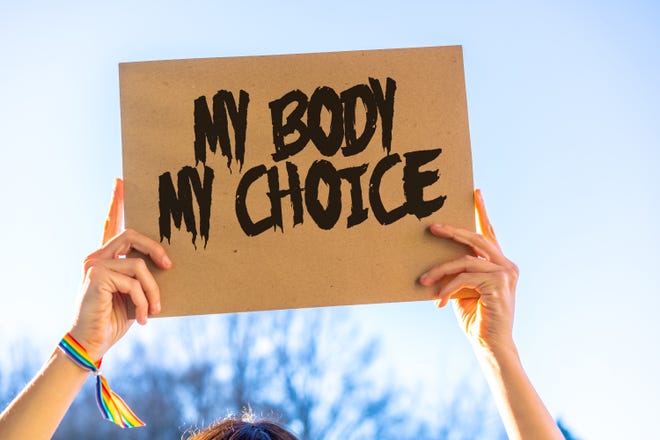

This could be a summer of protests. Do they make a difference?

[ad_1]

At 87, Loretta Weinberg has participated in a lot of demonstrations.

“The whole Vietnam movement, that’s where I walked in,” says Weinberg, who has marched for other issues, including women’s rights and school integration. She retired as New Jersey Senate majority leader earlier this year.

So, in early May, when Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion was leaked and she learned that the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision would likely be overturned, her first thought was “Didn’t we do this 50 years ago, and why am I in this discussion?”

Her second thought was to protest.

Protest movements can take a long time to fully achieve their aims — activism against the Vietnam War lasted 10 years — but experts say their value can be measured in other key ways: They change the way voters think, galvanize participants and show legislators the issues their constituents think are important.

“People are activated by the rollback of our democracy,” says Andrea McChristian, law and policy director at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice (NJISJ) in Newark. “Sometimes they feel that their voices aren’t heard. Mobilizing and getting out in the streets shows you care, pushes systems and challenges power.”

Weinberg bought poster board for the women’s group at her independent living community, a former nursery school teacher provided a shoebox of highlighters, and a retired art teacher made sure they kept the lines straight on their signs. About 50 men and women showed up May 13 to stand outside their building in Teaneck and share insights from the pre-Roe era, including a woman whose great-grandmother had died during an abortion.

The rally was covered by local media and avidly followed by the protesters’ grandchildren on social media, says Weinberg.

Though Gov. Phil Murphy signed a bill codifying New Jersey residents’ constitutional right to freedom of reproductive choice in January, “The leaked draft questions the right to privacy, which could mean that we see future opinions that will overturn the right to birth control or rights of equality for the LGBTQ community,” Weinberg says.

“We have a message for the generations behind us, so they can find out what life was like before Roe, when women were still pro-choice, but didn’t have access to safe health care services. And we’re showing our elected representatives and judiciary members that we value our liberties and the equality we expect to be granted under our laws,” she says.

Changing perceptions

Black Lives Matter is the most successful movement of our time, and supporters of other causes can learn lessons from it, says Maxwell Burkey, a visiting professor of African American studies and political science at The College of New Jersey. The BLM protest movement began in 2013, after the man who shot Black teen Trayvon Martin to death was acquitted; during the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, it encompassed 15 million to 26 million protesters.

“Bringing about change doesn’t mean you’re always storming the gates of the Bastille,” says Burkey, a River Edge resident. “It’s a slow, arduous process of changing the conversation.”

The term “super predator,” a major talking point of the 1994 crime bill, is an example, he says. BLM supporters made the case that it’s dehumanizing, and they helped shift the political conversation. Conversely, using the term “pro-abortion” destigmatizes the procedure, says Burkey.

Symbols are important, too. “Confederate statues were indelible features of the American landscape, and BLM transformed our conception of them from cultural artifacts to evidence of white nationalism in our midst,” he says.

While social media campaigns can be effective in sharing information and putting pressure on stakeholders, taking the time to show up in person and and make a public statement is powerful, says Burkey.

“Protest is inherently an embodied act,” he says. “To put pressure on, you have to be visible and show up.”

Tactics that are disruptive can add to a protest’s impact, he says.

“At the 1968 Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, women threw their bras into a ‘freedom trash can’ as street theater,” says Burkey. “In 1977, seeking federal recognition of their rights, people with disabilities occupied a government building in San Francisco for several days. In 2014, Black Lives Matter protesters shut down the FDR Drive in Manhattan.”

Enduring images that change hearts and minds often come out of these actions, he says — a demonstrator placing a flower in the barrel of a soldier’s gun at the March on the Pentagon in 1967; a Black woman in a flowing dress facing two Louisiana state troopers in riot gear in 2016.

McChristian recalls when NJISJ wanted Murphy to create a youth justice task force in late 2018, with the goal of closing the state’s youth prisons. “The governor said he had support from 94% of Black voters, so we called our effort ‘The Movement for the 94 Percent,’ ” she says. “We held a rally in a Newark church, and he created a task force the next day.”

Over Labor Day weekend 2020, after the mayor of Englewood Cliffs billed a teenager who had staged a modest rally for affordable housing $2,499 in police overtime, NAACP President Jeff Carter organized a march up East Palisade Avenue. “It had gotten media attention, but we brought more media attention,” says Carter. “The mayor wanted to march with us!” A day after making national headlines, he rescinded the bill.

“I think the rallies and protests impact government action and policy, even court decisions on some level,” says Mary Amoroso, a Bergen County Board of Commissioners member. “In New Jersey, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter rallies, we instituted a number of initiatives to better train and monitor police officers. Many police officers have come to understand that bodycams are not an invasion of their privacy, but a tool that makes crystal-clear they did the right thing.”

New Jersey police officers are also now barred from using physical or deadly force against civilians except as a last resort, and are required to intervene if they see another officer going too far.

The long game

While strategic victories sometimes come fast, it’s more common for progress to result from steady hard work. Toni Martin, a Montclair resident who once worked at the environmental nonprofit Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, says she appreciates demonstrations because “You don’t feel so alone.” But she marvels at how lifelong activists like Clearwater’s founder, Pete Seeger, kept the faith. “They had to know they weren’t going to win immediately,” she says.

When Martin wanted to get a rent control measure passed in her town, she says, she discovered that “you have to be relentless” to affect change. “People had been fighting for rent control in Montclair for 30 years,” she says.

During Montclair’s Fourth of July parade in 2019, she and a handful of compatriots brought their cause to the public by marching in Tenants Organization of Montclair T-shirts. “People would yell, ‘I’m a small landlord, and that won’t work!’ or ‘It’s about time!’, and we stepped out of the parade to engage them directly,” she says. On May 9, after two years of legal challenges, the Montclair Township Council passed a rent control ordinance — the first in its history.

For young people, the pace of change and scope of the issues that need to be addressed can be dispiriting. “The students I teach often seem overwhelmed by the challenges that face us, especially on the environment,” says Burkey. “They recognize problems, but there can be a fatalism.” To avoid that, he suggests focusing on local struggles where they can have an impact, such as protesting pollution at a particular site.

The first, but not last, step

Protesting isn’t the only way to affect change, of course. “I would be out protesting 24/7 if I thought it would move the dial even an inch in the right direction,” says North Jersey resident Janet Shapiro. Instead, she says, she contributes to the American Civil Liberties Union every month.

Cary Chevat, an activist in Montclair, has organized protests in the past, but warns that they can’t be seen as ends in themselves. “A lot of the time, it’s performative,” he says. “People hold up signs and feel good about it, and then they don’t vote.” Chevat notes that only 40% of eligible voters in Montclair turned out for the governor’s race in November. “Protests do energize people, but it can’t be theater,” he says. “You have to take it to the next step.”

“That is something our protesters need to focus on: getting relatives, friends and neighbors to register to vote, and then actually voting,” says Amoroso. “That is the ultimate exercise of your civic power and responsibility.”

Burkey agrees, though he points out that “What we vote for is often determined by how we engage. Many times, what’s on the menu is lacking, and movements change that menu.”

“All the movements I’ve been involved with, whether it was women’s rights, school integration in Teaneck, freedom of choice or Vietnam, all of them had positive outcomes in terms of improving the world around us,” says Weinberg.

The leaked Supreme Court draft opinion, she says, is the first time she’s ever heard of an attempt to turn the clock backward on women’s rights.

More:Rally held in Wayne as part of nationwide protests for women’s rights

More:Abortion is the word of the hour. But where did it come from?

More:A leaked Supreme Court decision could galvanize Democrats in midterms — or it may not

For information on where to vote and to confirm that you are registered, go to voter.svrs.nj.gov.

Cindy Schweich Handler is the editor of Montclair and Wayne Magazines, and a writer for The Record and Northjersey.com. Email: Handler@northjersey.com; Twitter: @CindyHandler

[ad_2]

Source link