Incoming State Health Officer Daniel Edney Long Defended Confederacy

[ad_1]

Upon his appointment as Mississippi’s next state health officer, Dr. Daniel P. Edney shared his priorities with a state still in the midst of a looming pandemic. “Following in the footsteps of Dr. Dobbs, I, too, hope to serve as a catalyst for change,” Edney wrote about outgoing State Health Officer Thomas Dobbs. Chief among his goals, Edney added, was “moving the needle in preventive health and health equity issues.”

Shortly after publishing Edney’s statement, the Mississippi Free Press obtained a pair of letters Edney had written in 1993 and 1994 when he was a newly graduated doctor in his 30s in Vicksburg. The letters published in The Clarion-Ledger depict a man heavily invested in the “Lost Cause” mythology of the Confederacy, defensive of his “love for the Confederate flag and (the song) Dixie,” and resistant to calls for these relics of a insurrection to preserve and extend slavery to be shifted out of prime locations in the public square.

For decades afterward, until 2013 at least, Edney was involved with the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization deeply invested in transmitting revisionist narratives of Confederate innocence, including the false notion that slavery was not central to the South’s secession. Edney is also listed as serving on the shrine board at Beauvoir, the coastal home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, until at least 2012. Beauvoir also doubles as a state headquarters of the SCV.

On June 1, in a lengthy interview, Edney told the Mississippi Free Press that these letters represented the perspective of a “young man with … very little experience of the real world, and a very limited knowledge of how others felt.” Edney said that hatred toward others was never an element of his Confederate apologia, but that “over the last 20 to 25 years, God has placed me on a different path.”

‘Equally Proud of Both’

In an article dated March 14, 1993, then-Clarion-Ledger columnist Joe Atkins compared the song “Dixie” to “Deutschland Uber Alles,” questioning the former’s long-time use as a proud, rousing fight song at University of Mississippi sports events (where he is now a journalism professor). “If we’re to hear Dixie today,” Atkins wrote, “maybe it should be played the way Germans play Deutschland, Deutschland Uber Alles: slow, full of pathos and some hard-gained wisdom.”

Eventually, the university went a step further than Atkins’ suggestion: “Dixie” is no longer played at UM sporting events. Gone, too, is Colonel Reb, the goateed plantation owner wearing Harvard crimson that was for so long the mascot of the university, and the sea of Confederate flags at sporting events. And UM recently moved the tall Confederate statue that had stood at its main entrance for many decades to its on-campus Confederate cemetery, but not without controversy.

In a letter to the editor dated April 2, 1993, Edney wrote in response that columnists like Atkins “were simply taking part in the liberal media led whipping of Mississippi and the South. There was really nothing new here except for the Nazi angle.”

“Well,” Edney added, “Mr. Atkins needs to realize that many of my family fought against Nazi Germany, and many of my family also fought against the Yankee invader, and I am equally proud of both.”

Edney’s letter challenging Atkins concludes with a series of rhetorical questions invoking the myth of the Black Confederate, claiming that 50,000 to 90,000 Black men, “both slaves and free men, (served) the Confederacy during the war.”

In truth, historians like Kevin M. Levin have highlighted a dearth of evidence for these many thousands of Black Confederate soldiers, which “Lost Cause” apologists often cite. Numerous enslaved Black camp followers were critical to the South’s war effort, providing logistical and manual labor, but to characterize their role as soldiers—or indeed, as willing participants at all—is a historical fabrication. Many Black southerners, in fact, defected to fight for the United States in the Civil War, including the Natchez U.S. Colored Troops.

In a separate letter printed July 22, 1994, Edney reacted to a Clarion-Ledger column that unfavorably compared Civil War reenactments to memorializations of civil rights struggles, such as Freedom Summer 1994.

“I could not believe that (the columnist) would insinuate that one of the most important episodes in American history needs to be ‘put behind us’ while the civil rights struggle should be preserved,” Edney wrote.

“Both,” he wrote then, “are worth preserving. … I personally want my children to learn about the courage, devotion to duty, and honor demonstrated by Southerners both black and white throughout history, and this certainly includes the Confederate soldier.”

In his June 1 interview with the Mississippi Free Press, Edney said that decades of working in free clinics and disaster response, in impoverished and minority communities both in Mississippi and abroad, had matured what was previously his deeply incurious perspective.

“I’ll tell you,” Edney said, “back when I was 30 years old, I was closed-minded. I was pretty hard-nosed about things. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned to be more open-minded—that it’s more important to listen than to talk, and to learn as much as you can.”

‘Big Time Implicit Bias’

Edney said that working as part of a disaster-medicine response team in Indonesia, Haiti, Lebanon, Nepal and Iraq and nations in Central America expanded his once-limited horizons. “I saw not just poverty impacting their access to health care, but racial issues, ethnic issues, religious issues … these experiences, over all that period of time, molded me and shaped me into who I am today.”

The incoming state health officer says his growth on racial inequity began “25 years ago, when I was led to help my church in Vicksburg start a medical, dental ministry to provide free medical care for the working poor. Our community did not have very good access to care,” he continued. “(Some) made too much for Medicaid,” Edney said, adding that it was a condition he could relate to. “Back when I was little, I didn’t realize that I was living in the home of working poor (parents) that had no insurance.”

That awareness followed him as an adult. “As a young physician, I saw the need for it, and (had) the ability to meet that need. That was really my first opportunity to work in minority communities, to work with the impoverished,” Edney said yesterday.

Continuing that work in his new role as state health officer will demand Edney address chronic health disparities across racial lines in Mississippi. Black Americans experience serious racial inequity in health care, and nowhere is that experience more pronounced than in Mississippi. Part of that, Edney said in the interview, is grappling with implicit bias, a process that he said took many years to understand.

“I had big-time implicit bias. Nick, I would have told you even 10 years ago that I did not have any implicit bias, that I care about all my patients, love my patients, and serve my patients,” he said. “Knowing what I know now, and understanding what I understand, clearly as a clinician I had implicit bias … going back to when I was 30 years old, the fact that there was no hatred in my heart doesn’t matter, (because) there was bias there.”

While Edney credited his long career in health care and work abroad with expanding his horizons, he also said that beginning treatment for an addiction to pain pills in 2013 was a turning point for him. “I almost became a statistic,” Edney said.

“I went to treatment on March 3rd, 2013,” he continued. “That (process) for me was planting-the-flag time, of everything changing.” Edney said his recovery—both from drugs and from bias—could be an instructive process for others. “In recovery, we help those who are still sick and suffering by showing them the solution, and (by) sharing our experience, strength and hope,” he said.

Relationship with SCV Continued

While Dr. Edney is adamant that he has long since walked away from his Confederate advocacy, his presentation of the timeline of that change was not always accurate in his June 1 interview with the Mississippi Free Press.

“These are also things I haven’t thought about in decades,” Edney said early in the interview. “I have spoken more about these issues in 24 hours than I have in 24 years.” He said his involvement with both the Sons of Confederate Veterans and board leadership at Beauvoir ceased long ago. “I’ve not had any work with them, or attended meetings, or kept up membership for a very long time—15 years or more,” he added.

But state records and a Sons of Confederate Veterans newsletter show that while Edney’s public letters in defense of Confederate honor may have ceased before the turn of the millennium, his relationship with the Sons of Confederate Veterans persisted well into the 21st century.

As recently as September 2013, Edney spoke at the Lt. General John C. Pemberton Camp 1354 meeting of the Sons of Confederate Veterans in Vicksburg, Miss.

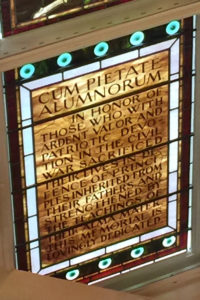

At that meeting, Edney presented a program detailing the history and “valor” of the University Greys, Confederate soldiers drawn from students at the University of Mississippi during the Civil War, largely if not entirely a group of slave-owning planters’ sons. Edney’s presentation concluded with a description of “the three Confederate items at Ole Miss that should be defended,” including the Tiffany stained-glass memorial window to the Greys in Ventress Hall, and both the Confederate Monument and the Confederate cemetery on campus.

The large stained-glass window in Ventress Hall depicts illuminated Confederates as fighting for an honorable cause, placed “in honor of those who with ardent valor and patriotic devotion in the civil war sacrificed their lives in defence of principles inherited from their fathers.” Ventress is an active building containing the offices of the College of Liberal Arts.

When this reporter presented the content of that 2013 newsletter to Edney later in the interview, he did not dispute that he had appeared at that meeting to offer the presentation described in the group’s newsletter, but said the “defense” of the monuments came “purely from a historical standpoint.” Now, Edney said, “I’m totally in favor of the monuments being moved.”

“Even from the standpoint of historical artifacts, my viewpoints have changed,” Edney said. “I voted to support changing the flag. I’m in full support of the new flag. I’m in support of keeping monuments and artifacts in historical context,” Edney concluded. “They need to be preserved appropriately and in context. I’m a supporter of preserving artifacts in museums.”

‘Exactly The Opposite Idea’

The Sons of Confederate Veterans has long promoted Lost Cause narratives that downplay slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War and recasts Confederates and slaveowners as heroic figures. The organization runs Beauvoir, the Gulf Coast home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, which now operates as a museum that annually receives $100,000 from the State of Mississippi.

The state-funded museum has long sold books popular inside the neo-Confederate movement, including “The South Was Right” by twin brothers James Ronald Kennedy and Walter Donald Kennedy, which included a call for a second secession. Walter Kennedy was also a co-founder of the “pro-white” League of the South in 1994. That is the same group caught on video trying to film a propaganda video at an Emmett Till memorial site in Tallahatchie County in 2019.

Since 1993, governors, including current Gov. Tate Reeves, have approved the SCV’s request to proclaim April as “Confederate Heritage Month.”

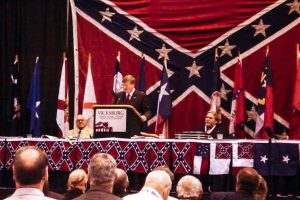

In July 2013, the Sons of Confederate Veterans held its annual reunion in Edney’s hometown of Vicksburg, where speakers addressed the crowd while standing in front of a massive Confederate flag with cotton arrangements on either side of them. Reeves, who was Mississippi’s lieutenant governor at the time, attended as a special guest, praising the SCV for its focus on Confederate history. Afterward, another speaker compared compared the North’s treatment of the Confederate South to how the Nazis treated Jewish people during the Holocaust.

SCV claims the Civil War was not primarily fought over slavery despite the fact that Mississippi’s 1861 Declaration of Secession said that the state’s “position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.” When Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens announced the Confederate Constitution in 1861, he said in the openly white-supremacist “Cornerstone speech” that the Confederacy was a refutation of the Declaration of Independence’s claim that “all men are created equal.”

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition,” he said. “This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

In the June 1 interview, Edney said that actions and statements on the part of the national organization eventually repelled him from membership and, finally, any participation at all.

“Over time, my thoughts and feelings just didn’t match up with everybody else’s (in SCV). I purposefully separated myself,” Edney said when explaining the 2013 presentation defending Confederate memorials. “I would go to meetings with the local guys in Vicksburg as friends, but in terms of the national organization, people that I did not agree with and could not support were taking control. That’s when I just walked away from it.”

‘We Did That By Listening’

Now, the task ahead of Edney and the rest of the Mississippi State Department of Health is immense and relies on trust-building across demographics. “Health equity” is only a phrase, but one concerned with great material need on the part of Mississippians. “Our number-one (task) is to move the needle on maternal and infant mortality rates in Mississippi,” Edney said.

Those high death rates, higher among Black Mississippians, is strong evidence for continuing health equities in Mississippi. To date, the Mississippi Legislature has rejected attempts to address some of those critical health disparities, including extending Medicaid postpartum to mothers in the state with the highest rate of maternal mortality in the nation.

It is no surprise to Edney that Mississippi is ranked last in outcomes, but the depth of the state’s health disparities are catastrophic, he said. “Look at 47th, 48th, 49th, and then you see us plunge off the cliff,” Edney explained.

“(Mothers) need prenatal care. (Maybe) even if they have Medicaid, they can’t get to the doctor, can’t get the right food, can’t get to the emergency room when they’re in labor. What if they lose their Medicaid two months after they give birth, but they still have heart failure, or they have postpartum depression? These are all equity issues,” Edney said.

They are also health-equity barriers that had long been under-addressed when the pandemic came to Mississippi, magnifying the realities.

Part of the equity solution, Edney acknowledged, is the same process that he has had to confront personally. “Under Dr. (Thomas) Dobbs’ and Dr. Victor Sutton’s leadership, the health-equity department did what they needed to do to improve vaccination rates. And it worked! We did that by listening,” Edney said.

“We did that by developing relationships in the black community. We did that by letting our health-equity people work with the leaders in the Black community all over the state to come up with solutions that would work in their communities, instead of us going and telling them we’re the health department, you need to do what we say.”

Beyond listening, Edney admitted that the resources available for addressing critical issues beyond the pandemic would be more limited than the huge tap of federal support for COVID. “What we can do is … deploy what resources we have in a thoughtful and equitable manner, in a way that will overcome some of these disparities,” he said.

‘I’ve Made Some Mistakes’

In the interview, Edney presented himself as a changed man, whose growth could be instructive to the many others across the state he says share his limitations and biases.

“Here I am,” he said, “A recovering physician—recovering from implicit bias, in the midst of structural racism. But I will continue to work to recover. And I plan to leverage my recovery in this way to change the system, because if we don’t (change), our mothers and our babies will continue to die.”

“The state is changing for the good,” Edney said. “People change. And I hope that I’ve changed for the good. I plan to use my story in its entirety for (everyone’s) benefit. I will employ all my knowledge, expertise and experience for their benefit.”

“I’ve made some mistakes,” Edney finished. “I’m owning it. I’m not trying to dodge it. It is what it is. I wish I had more sense as a younger man, but today I do. And I’m grateful. Man, I am so grateful for where I am today. And let me tell you something: I would not be with the health department if I didn’t feel passionately about this.”

Editor Donna Ladd and Senior Reporter Ashton Pittman contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: Former Clarion-Ledger columnist and current University of Mississippi journalism professor Joe Atkins is on the advisory board of the Mississippi Free Press. He was not consulted for this article.

[ad_2]

Source link