3 ways community paramedics can assist with after-stroke care

[ad_1]

By Mark E. Milliron, MS, MPA, MHS, EMT, CCHW

Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death (not including COVID-19) in the United States. Nearly 800,000 people will suffer a stroke each year; and for Black Americans, the risk of a first stroke is nearly twice as high, with the highest death rate.

Strokes are also the leading cause of long-term disability usage; in 2017, $53 billion was spent between related medical expenses and lost workdays [1].

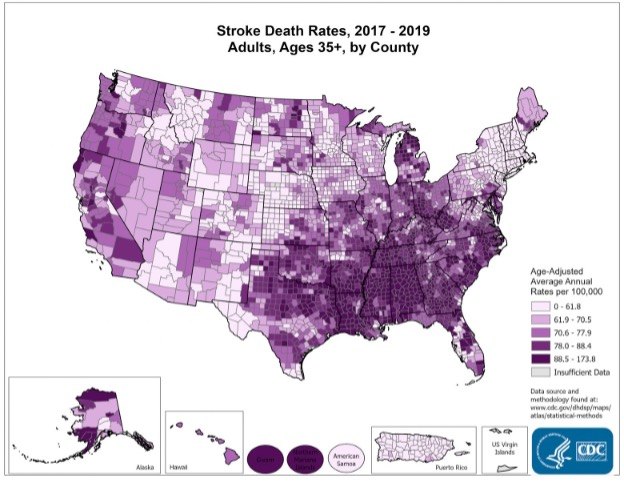

Distribution and frequency of strokes by U.S. state. (Photo/CDC)

A study of 2,706 patients discharged between 2007-2009 found that 6.4% were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days. Of those, 29% were found to be readmitted after inadequate outpatient care coordination and 4% readmitted after being discharged with inadequate discharge instructions [2]. Another study from the 2013 Nationwide Readmission Database of 319,317 patients with acute ischemic stroke – which accounts for 87% of strokes – found 12.1% of patients were readmitted. Factors for readmission included patients who were older, had Medicare coverage, and a lower household income [3].

How to identify a recurring stroke

Most providers are familiar with the acronym FAST – Face, Arm, Speech, Time – to identify a stroke. Recurring strokes have similar warning signs [4]:

- Sudden trouble with vision from one or both eyes

- Sudden difficulties with walking, coordination, dizziness, and/or balance

- Sudden trouble with speaking, confusion, memory, judgment or understanding

- Sudden numbness/weakness of the face, arms or legs, particularly on one side of the body

- Sudden severe headache (described by survivors as “the worst headache of their life”)

- Difficulty swallowing

Community paramedicine follow-up and care after hospital discharge can help alleviate the impact of factors such as poverty and access to medical care, improve patient and family education, and help prevent the negative economic impact following a stroke.

Community paramedicine’s impact on stroke care

There are several ways community paramedics can play a key role in helping patients avoid a second stroke, mostly centered around discharge instruction compliance [5].

1. Smoking cessation. Community paramedics should ensure patients have access to an effective program to help them stop smoking, due to the high risk of stroke it presents. However, nicotine can be very addictive, and relapse is not uncommon – nonjudgmental support from family and friends is important. Some obstacles to quitting include:

- Strong cravings

- Strong emotions

- Difficulty concentrating

- Difficulty sleeping

- Hunger

- Weight gain

- Anxiety

Look for a support system that works for the patient. Start with the Quitline at 800-QUIT-NOW (800-784-8669). The CDC also offers several smoking cessation resources on its How to Quit Smoking site, including tips from former smokers, a step-by-step guide to quitting cigarettes and access to the quitSTART app for customized goals and motivational tips [12].

2. Prescription compliance. Following a stroke, many patients are sent home on prescriptions that are vital to preventing a secondary stroke or more complex medical conditions, including:

- Atrial fibrillation. AFib is associated with roughly five times increase in ischemic stroke and is the cause of about 1 in 7 strokes. These strokes tend to be more severe than other strokes [6]. Post-discharge treatment may include blood thinners, beta blockers, and/or calcium channel blockers. A study of patients with AFib following stroke or TIA was conducted at 3 and 12 months after discharge to understand medication use behavior [7]. AFib was present in 11.8% of patients. Common antithrombotic therapy used was mostly warfarin followed by aspirin and then clopidogrel (Plavix).

- High cholesterol. A study of 9,380 patients discharged from 134 Veterans Health Administration facilities found that 34.1% were discharged off a statin medication. Reduction in cholesterol levels is associated with reduced risk of subsequent stroke [9]. Compliance can also be monitored and encouraged to reduce chronic conditions, reduce possible future strokes, and reduce mortality.

- Diabetes. A common risk factor for stroke is diabetes, including those with prediabetes. Over time, a person with excessive blood glucose can result in fatty deposits building up in their blood vessels. These people should be screened for excessive belly fat (men with a waist over 40 inches and women over 35 inches). Risk factors include:

- An A1C level over 7%

- Blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg

- Total cholesterol greater than 150 mg/dL and LDL over 100 mg/dL

- Smoking

To prevent another stroke, patients should maintain a heart-healthy diet, maintain a healthy weight, exercise daily, avoid smoking, limit alcohol and manage stress [10].

Despite the medical need, many stroke patients do not adhere to their prescribed medications for a variety of reasons, including [8]:

- Fear

- Cost

- Too many medications

- Lack of symptoms

- Mistrust

- Worry

- Depression

Prescribed medications can be prohibitively expensive for patients who do not have prescription insurance coverage. The discharging hospital or a community medical clinic may be able to support patients in accessing prescription medication programs through pharmaceutical manufacturer’s medication assistance programs. There are also websites that can search for assistance programs, such as the Medicine Assistance Tool, and local medicine assistance teams may develop their own list of pharmaceutical assistance programs.

3. Risk screenings. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing is a common condition following both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. A study found that nearly 40% of all stroke patients had dysphagia [11]. The Dysphagia Outcome Severity Scale (DOSS) can be used to assess stroke patients through several questions:

- Is the patient coughing during eating and drinking?

- Does the patient have a wet, gurgling voice while eating and drinking?

- Is extra effort needed to chew or swallow?

- Is there food or liquid leaking from the mouth?

- Is food retained in the mouth?

- Can the patient sit in an upright position?

- Was the patient on a regular diet prior to their stroke (thin liquids, no alteration in food textures)?

- Is the patient alert and cooperative?

- Can the patient follow commands?

- Does the patient have normal facial symmetry (no droop, new or residual or resolved)?

- Can the patient stick tongue straight out without deviation?

- Does the patient exhibit a normal voice and speech pattern with no aphasia, slurring, garbled or delayed speech?

- Can the patient manage secretions with no drooling or slurping?

- Can the patient cough and clear their throat?

Why ongoing reassessments are key to long-term health

Generally, a stroke can affect speech, movement and memory, which in turn affect the patient’s daily living activities. Ongoing reassessment can help the patient understand their current needs, as well as inform family members, caregivers, and medical providers about possible complications and adjustments. Various organizations have developed checklists to assess a patient’s status [13-15]. Key indicators that patients, family members and caregivers should watch for include:

- Pneumonia. This can especially be a complication following mechanical ventilation, multiple stroke lesions or posterior circulation strokes. Atelectasis is the collapse of all or part of a lung and can be a risk following anesthesia and prolonged bed rest with few changes in position.

- Swallowing. Dysphagia can lead to aspiration of food or liquids causing pneumonia or ultimately chronic lung disease, dehydration, less enjoyment of eating or drinking, and embarrassment or isolation in social situations.

- Decreased mobility. A lack of movement can increase the risk for stroke patients.

- Poor oral hygiene. This can lead to increased risk of aspiration, periodontal disease and malnutrition.

- Pulmonary hygiene. A stroke patient may find difficulty in keeping their trachea and bronchial tree free of mucus and secretions.

- Aspiration. Mitigation factors include elevating the head during meals, lower intake amount, position of head while swallowing, and the use of a straw.

- Malnutrition. If observed, a dietician consultation would be appropriate along with a speech and language pathologist consultation. The family may be involved in feeding and menu planning.

- Urinary tract infection. If the patient is using a catheter, a UTI may occur. Watch for urinary retention. Does the patient use a securing device? Is the collection bag below patient’s bladder?

- Fall risk. Conduct an environmental check of the patient’s home to check for trip hazards such as extension cords and area rugs. If needed, coordinate a PT consultation. Consider the patient’s visual acuity, as well as the patient’s impulsivity, confusion and need for repeated explanations.

- Self-care deficits. Does the patient have any feeding, bathing, dressing or mobility limitations that could contribute to an injury?

- Depression. A psychiatric consultation may be appropriate.

- Deep vein thrombosis. A DVT may result from reduced mobility. Sequential compression devices may be beneficial in improving blood flow in the legs.

All of this information can be shared with the patient, family members, and caregivers who may be coming into the patient’s home.

Successful after-stroke care is a team effort

Following a stroke, it’s important for connected family and loved ones to understand the patient’s short- and long-term physical and occupational therapy goals, speech and language pathology goals, as well as the operation and maintenance of adaptive equipment.

Make sure that everyone knows and understands the BE-FAST mnemonic to recognize a stroke – balance, eyes, face, arm, speech, and time – as well as the differences between an ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [16]. Time is of the essence when a stroke occurs, and EMS should be notified immediately.

Ensure family members are aware of what medications have been prescribed and how they are administered and stress the importance of follow-up appointments with providers. Help them to understand the individual patient’s risk factors, both the uncontrollable, such as age, race and prior stroke and those that can be controlled, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, smoking and tobacco use, alcohol and other drug use, and weight.

Ultimately, community paramedics want to give the patient, family and other caregivers the tools they need to prevent another stroke in the future.

Read more:

Time-critical: The importance of stroke triage for EMS

Rapid restoration of blood flow is the most critical determiner of functional brain survival

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Stroke Facts,” 5 April 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm.

- F. Nahab, J. Takesaka, E. Mailyan, L. Judd, S. Culler, A. Webb, M. Frankel, D. Choi and S. Helmers, “Avoidable 30-Day Readmissions Among Patients With Stroke and Other Cerebrovascular Disease,” The Neurohospitalist, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7-11, 1 January 2012.

- F. S. Vahidy, J. P. Donnelly, L. D. McCullough, J. E. Tyson, C. C. Miller, A. K. Boehme, S. I. Savitz and K. C. Albright, “Nationwide Estimates of 30-Day Readmission in Patients With Ischemic Stroke,” vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 1386-1388, 7 April 2017.

- J. M. Neal, “Warningn signs and symptoms of another stroke,” University of Toledo, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.utoledo.edu/depts/csa/caringweb/symptoms.html.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine, “3 ways to avoid a second stroke,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/stroke/3-ways-to-avoid-a-second-stroke.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion , Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, “Atrial Fibrillation,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 27 September 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/atrial_fibrillation.htm.

- B. R. S. D. M. O. Renato D. Lopes, X. Zhao, W. Pan, C. D. Bushnell and E. D. Peterson, “Antithrombotic Therapy Use at Discharge and 1 Year in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Acute Stroke,” vol. 42, no. 12, p. 3477–3483, 8 September 2011.

- American Medical Association, “8 reasons patients don’t take their medications,” 2 December 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/patient-support-advocacy/8-reasons-patients-dont-take-their-medications.

- J. L. Dearborn-Tomazos, X. Hu, D. M. Bravata, M. A. Phadke, F. M. Baye, L. J. Myers, J. Concato, A. J. Zillich, M. J. Reeves and J. J. Sico, “Deintensification or No Statin Treatment Is Associated With Higher Mortality in Patients With Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack,” Stroke, vol. 52, no. 8, p. 2521–2529, 21 May 2021.

- American Heart Association, “Diabetes and Stroke Prevention,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-risk-factors/diabetes-and-stroke-prevention.

- E. M. Khedr, M. A. Abbass, R. K. Soliman, A. F. Zaki and A. Gamea, “Post-stroke dysphagia: frequency, risk factors, and topographic representation: hospital-based study,” The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, vol. 57, no. 23, 10 February 2021.

- Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, “How to Quit Smoking,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28 February 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/quit-smoking/index.html.

- World Stroke Organization, “Stroke recovery and support,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.world-stroke.org/world-stroke-day-campaign/why-stroke-matters/life-after-stroke/stroke-recovery-and-support.

- International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, ” Post-Stroke Checklist (PSC),” [Online]. Available: https://www.isprm.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/PSC-WSO-Version-English-03-27-13.pdf.

- Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, “Post-Stroke Checklist,” 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.strokebestpractices.ca/-/media/1-stroke-best-practices/resources/patient-resources/002-17_csbp_post_stroke_checklist_85x11_en_v1.ashx.

- S. Aroor, R. Singh and L. B. Goldstein, “Sushanth Aroor; Rajpreet Singh; Larry B. Goldstein,” Stroke, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 479-481, February 2017.

[ad_2]

Source link