Affirmative action: Is this the end? What comes next?

[ad_1]

High school seniors all over the United States this month are getting their college acceptance letters. And it may be the last time that those letters go out under the system of affirmative action that has been in place in the U.S. for more than 50 years.

By the end of June, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on a case that may well end the practice of considering race as one facet of admissions in all U.S.-based institutions of higher learning.

What would the end of affirmative action mean for students and their families, particularly first-generation and low-income students? And how will colleges and universities pivot from what has been an entrenched status quo?

Why We Wrote This

What would the end of affirmative action mean for students and their families? And how will colleges and universities pivot from what has been an entrenched status quo?

What is the Supreme Court case? Why is it happening?

On three different occasions, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld, on narrow grounds, the constitutionality of race-based affirmative action in university admissions. But as it prepares to rule in two cases involving admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina (UNC), the court appears poised to overturn that precedent.

Conversations around race-based affirmative action began in the 1960s, with Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson arguing that the policies were needed to help historically disadvantaged racial groups, particularly African Americans, achieve full equality.

When the Supreme Court first heard a constitutional challenge to affirmative action in college admissions, in 1978, it upheld the system – but not in the way Presidents Kennedy and Johnson articulated. In his controlling opinion, Justice Lewis Powell wrote that affirmative action is lawful because it furthers a state’s “compelling interest” of attaining a diverse student body.

“Anyone who has been involved in higher education understands diversity is a good thing,” says Geoffrey Stone, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, “but that’s not what [affirmative action] is really about.”

Since that 1978 case, he adds, diversity, not social justice, “has become the center point in how the court talks about affirmative action.”

While it has narrowed at the margins the lawfulness of affirmative action policies in college admissions – racial quotas are not allowed, for example – the high court has repeatedly ruled that the Constitution protects such policies because of those diversity interests. In a 2002 decision about a University of Michigan policy, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.”

Two decades later, the Harvard and UNC cases – both brought by the group Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) – are testing that aspiration. One case argues that Harvard’s policy unlawfully discriminates against Asian American applicants, and the UNC case makes similar arguments regarding white and Asian American applicants. Both universities won in the lower courts.

But at a five-hour oral argument last October, the court’s six conservative justices voiced deep skepticism about the universities’ policies and the court’s precedents.

“I don’t have a clue what [‘diversity’] means,” said Justice Clarence Thomas. “I didn’t go to racially diverse schools, but there were educational benefits.”

“When does it end?” asked Justice Amy Coney Barrett. “What if it continues to be difficult in another 25 years?”

How is it likely to turn out? What is at stake?

The Supreme Court appears likely to rule against Harvard and UNC. The next, and harder to predict, question: How broad will the court’s ruling be?

The answer to that question may tie back to the court’s blockbuster ruling last term: the decision to overturn the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health.

“They might do what they did in Dobbs and overrule all the precedents that have dealt with affirmative action,” says Professor Stone, co-author of a recent book arguing that race-based affirmative action is constitutional on social justice grounds. “But after Dobbs they may be a little more cautious, they may want to not look as partisan.”

Either way, universities should be preparing for life after race-based affirmative action, experts say. Exactly what they’ll be permitted to do won’t be clear until the Supreme Court’s decision is released (expected in June), however. And whatever the court does say, there is likely to be confusion.

“It will be interesting to see what institutions will do in that world,” says Professor Stone. “I don’t have a simple solution.”

But banning affirmative action, he adds, “isn’t going to make the issue go away.”

Giving extra weight to socioeconomic status is one possible solution, experts say.

Richard Kahlenberg, a nonresident scholar at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, testified on this point as an expert witness at the district court level in the Harvard and UNC cases. He believes that universities focusing on socioeconomic diversity could even improve on the affirmative action policies of the past half-century by better addressing their social justice roots.

“Looking at economic disadvantages means we’re not ignorant of our history,” he says. “It’s precisely because of our history of discrimination that Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately poor.”

Conservative jurists like Justice Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito have both spoken favorably of admissions policies that favor lower-income students. An oft-cited model is Texas’s “Top 10 Percent” law, which since 1998 guarantees all students in the top 10% of their high school graduating class admission to all state-funded universities.

“Right now racial preferences create racial diversity but very little socioeconomic diversity,” he adds. “So long as selective colleges are seen as a bastion for the wealthy, that’s bad for the country.”

What effect would banning affirmative action have?

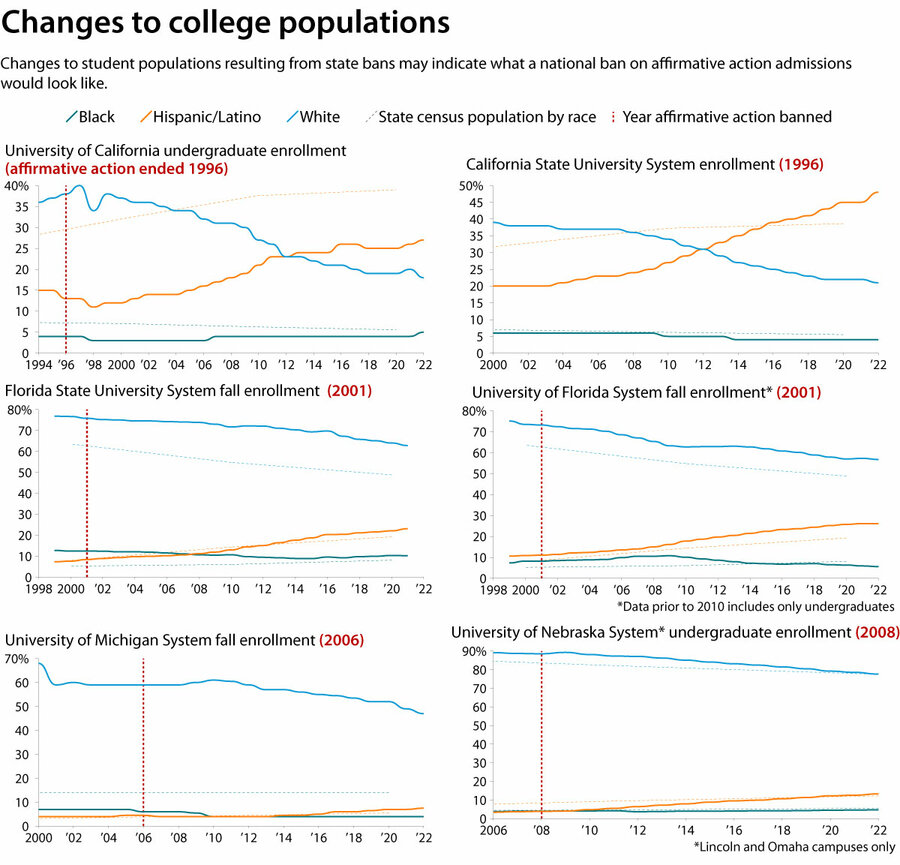

Affirmative action has been banned in nine states thus far. California moved first, when voters set Proposition 209 in action in 1996. It officially went into effect for public universities in 1998. Some of the most selective schools in the state system, such as the University of California, Los Angeles and the University of California, Berkeley, suffered steep declines in enrollment of underserved minority groups, who are economically or educationally disadvantaged as opposed to minority groups that may not face those issues. Underserved minority groups in California generally had a more difficult time getting into more selective schools.

Soon after the country’s largest state approved the measure, others followed. They included Florida (2001), Michigan (2006), Nebraska (2008), Arizona (2010), New Hampshire and Oklahoma (both in 2012), Washington (2019), and Idaho (2020).

Michigan public universities suffered enrollment declines, particularly among Black students. Representatives from schools in Michigan and California filed briefs to the Supreme Court arguing that racial diversity is impossible without affirmative action. The 10 schools in the University of California system educate more than 294,000 students and suffered precipitous drops in enrollment of underserved students after Prop 209. The most selective schools had a more than 50% drop in enrollment from those groups.

The California brief went further: “UC’s decades-long experience with race-neutral approaches demonstrates that highly competitive universities may not be able to achieve the benefits of student body diversity through race-neutral measures alone. To fulfill their role of preparing successive generations of citizens to succeed in an increasingly diverse Nation, universities must retain the ability to engage in the limited consideration of race contemplated by this Court’s precedents.”

The University of Michigan said it was convinced of the broad educational benefits of a diverse student body. After the state banned affirmative action there in 2006 its Black population fell almost by half and it suffered losses to its Native American population. Michigan called its cooperation involuntary and said that it had been an unsuccessful experiment.

“The universities’ 15-year long experiment in race-neutral admissions thus is a cautionary tale that underscores the compelling need for selective universities to be able to consider race as one of many background factors about applicants,” the Michigan brief stated.

For its part, Florida argued that diversity could be achieved without special admissions and supported this with the percentage of Hispanic students enrolled in public schools before and after the state banned affirmative action.

How should colleges and universities prepare?

While the court’s decision is still unknown, many believe that it will abolish affirmative action in admissions, based on oral arguments. That could come in many forms, such as preventing applicants from being able to check a box for their race or ethnicity on college applications.

“But they might say you can’t take anything into consideration that has any sort of reference to race, and then that would include an essay, for example, or scholarship programs and things like that,” says Angel Pérez, chief executive officer of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Dr. Pérez says one of the biggest questions that high school guidance counselors ask is if students will be able to talk about their stories in an essay, which is particularly important for low-income or first-generation students of color, to present obstacles and struggles that they overcame. Many counselors encourage students to talk about lived experiences in their essays as a way to fully present themselves to universities. Essay questions are staple features on individual school applications and the common application, which many colleges and universities use.

Counselors sometimes specifically encourage students of color to talk about lived experiences and to apply for race-based scholarships, but that could be in jeopardy, Dr. Pérez says.

“Here’s where it gets more complicated. What happens to those scholarship programs?” he asks. “We don’t know.”

The issue is complex because it also informs the way development offices at colleges fundraise and engage alumni and donors for scholarship money based on particular communities. Some of those initiatives include drives to increase Black and Latino enrollment, says Dr. Pérez, who worked both as a high school counselor and in college admissions.

“College advising is going to change as a result, and high school counselors will need to relearn how institutions are going to function. That’s going to have a trickle-down effect on the entire sector,” he says.

Something else that is unknown but was discussed in oral arguments that might come from this case is the exclusion of legacy consideration, which currently gives potential students who are children of prominent alumni an admittance advantage. Some schools are taking steps to pivot before a decision is reached. Ivy League school Columbia University recently eliminated test scores for admissions consideration. Standardized tests have shown historically to favor mostly white students who can afford to spend money on test prep classes, as opposed to the underrepresented groups. Also, schools currently buy lists of names of students based on test scores, geography, and racial identity.

“So a school would say, ‘I want to buy the names of every Latinx student in Washington, D.C., who has above a 500 on the English essay,’” explains Dr. Pérez. “If that tool is taken away there goes another kind of marketing pipeline that used to be very traditional in the college admissions pipeline.”

[ad_2]

Source link