Targeting of Asian Americans mobilizes new generation of activists

[ad_1]

The targeting of Asian Americans in acts of hate and violence increased dramatically with the onset of the pandemic.

San Francisco alone saw 60 reported hate crimes against Asians and Asian-owned businesses last year, representing a 567% increase between 2020 and 2021, according to police data. The campaign to recall San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin included ads from victims’ families arguing that the district attorney had failed to adequately address violence against Asians. Results show that more than two-thirds of voters in the Chinatown neighborhood supported the recall.

Nationwide, almost 11,000 anti-Asian bias incidents between the start of the pandemic and December 2021 were reported to Stop AAPI Hate, a national coalition that tracks acts of hate, violence and bigotry against Asian Americans.

The targeting of this community, coupled with the harsh impacts of the pandemic, mobilized a new generation of activists utilizing different strategies to stop the hate and advance justice. It’s activism that Diane Fujino, a professor of Asian American studies at UC Santa Barbara, calls “invisible.”

“Despite the long history of Asian American resistance against structural racism and other dimensions of oppression, it seems that people rarely know about Asian American activism,” Fujino said. It is largely unseen because of the myth that Asian Americans are a successful minority group focused only on education and business, she added.

As Fujino’s work documents, Asian Americans have always been active in working against institutional racism and for social change.

The organizing that has arisen post-pandemic is as diverse as the community itself. While there are many veteran Asian American activists and organizations, The Chronicle is profiling three individuals in the Chinese American community who are part of a new generation working for change in San Francisco and beyond.

Justin Zhu, 32, San Francisco, co-founder, Stand With Asian Americans

When a white gunman killed six Asian women in the Atlanta area last year, Justin Zhu’s life in San Francisco changed. It was March 2021, and Zhu, a successful tech startup co-founder, was deeply rattled by the horror of the shootings.

It “was a breaking point for me,” Zhu said. “We are being killed. We have to speak out.”

As he processed the racist acts, Zhu pivoted from his Silicon Valley career to a very different type of venture. He co-founded a nonprofit organization that would expose hate against his community and work to stop it.

Having already built the $2 billion marketing platform Iterable, Zhu, who grew up in China, wondered, Why not use the same strategies to combat racism and foster equality?

Zhu saw an important need “to have a more equitable distribution of resources and change the (economic) model that really focuses on exploitation.”

He immersed himself in the history of an iconic Bay Area social movement that he thought might provide inspiration.

“The Black Panthers really appealed to the shared liberation of people,” including globally in Vietnam and Angola, Zhu said. From the Black Lives Matter movement to LGBTQ struggles for equality, he had one big question: “How do we build that rainbow coalition of the oppressed minority groups together?”

He launched Stand With Asian Americans with co-founders Dave Lu, managing partner at Hyphen Capital, a San Francisco firm that invests in Asian American startups, and Wendy Nguyen, a startup marketing executive who previously launched a vote-by-mail nonprofit in 2020, hoping other business leaders would speak out on the increasing acts of hate against the community.

Justin Zhu, co-founder and executive director of Stand with Asian Americans, takes a phone call during lunch in Chinatown. The March 2021 killing of six Asian woman in the Atlanta area galvanized him.

Stephen Lam/The Chronicle“To see the attacks happen in our backyard and not seeing it debated, and also seeing further injustices in the legal process — that was the last straw,” Zhu said. In too many incidents, he said, there was a lack of police or prosecutorial action to find perpetrators or hold them accountable.

Amid a global pandemic and unable to meet in person, the young entrepreneur put word out to San Francisco’s Asian American community to gather on Zoom and process what was occurring. The Bay Area “is a third Asian American, (and) we don’t feel safe,” Zhu said. “The (Atlanta) shootings brought back memories of being attacked and bullied that’s been suppressed … and so that triggered going from fear to anger.”

Their first action was buying a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal headlined “Enough.” It was signed by 100 influential Silicon Valley Asian American business leaders pledging to give $10 million to community groups working to stop the violence. They also created a fund to help Asian women take action against workplace harassment and exploitation.

Signatories included the founder of Zoom and co-founders of DoorDash, Yahoo!, Stitch Fix and YouTube. In the months after the ad was published, the number of signatures jumped to 8,000, Zhu said.

Zhu is activating a constituency that can use its social capital to bring a different kind of awareness. To date, the group has raised $2 million and given grants to Bay Area and national Asian American groups totaling $500,000, Zhu told The Chronicle.

His group made the Atlanta spa shootings the focal point of its organizing. Gathering late nights to discuss tactics and strategy in the basement of Chinatown’s Lion’s Den club while karaoke singers partied above them, this Millennial generation of activists broadened from business leaders to include lawyers, bankers, writers and other professionals. They were all Asian American and all determined to change things.

When acts of hate happened in the Bay Area, Stand With Asian Americans quickly mobilized to bring attention. Zhu and his volunteers planned local protests to rally support for victims of hate crimes. They also coordinated with national groups to connect their protests to a larger constituency.

In March, on the first anniversary of the Atlanta shootings, Stand With Asian Americans helped organize a San Francisco event to remember the victims and build community resilience. The event featured mental health resources and self-defense classes. Women spoke out about the everyday violence and hate they face.

Zhu knows there is a long road ahead, but his dream is simultaneously big and very simple. “We could rebuild the empire so that it treats us fundamentally as equal human beings.”

Yulian Luo, 42, Chinatown, San Francisco, community organizer, Chinese Progressive Association

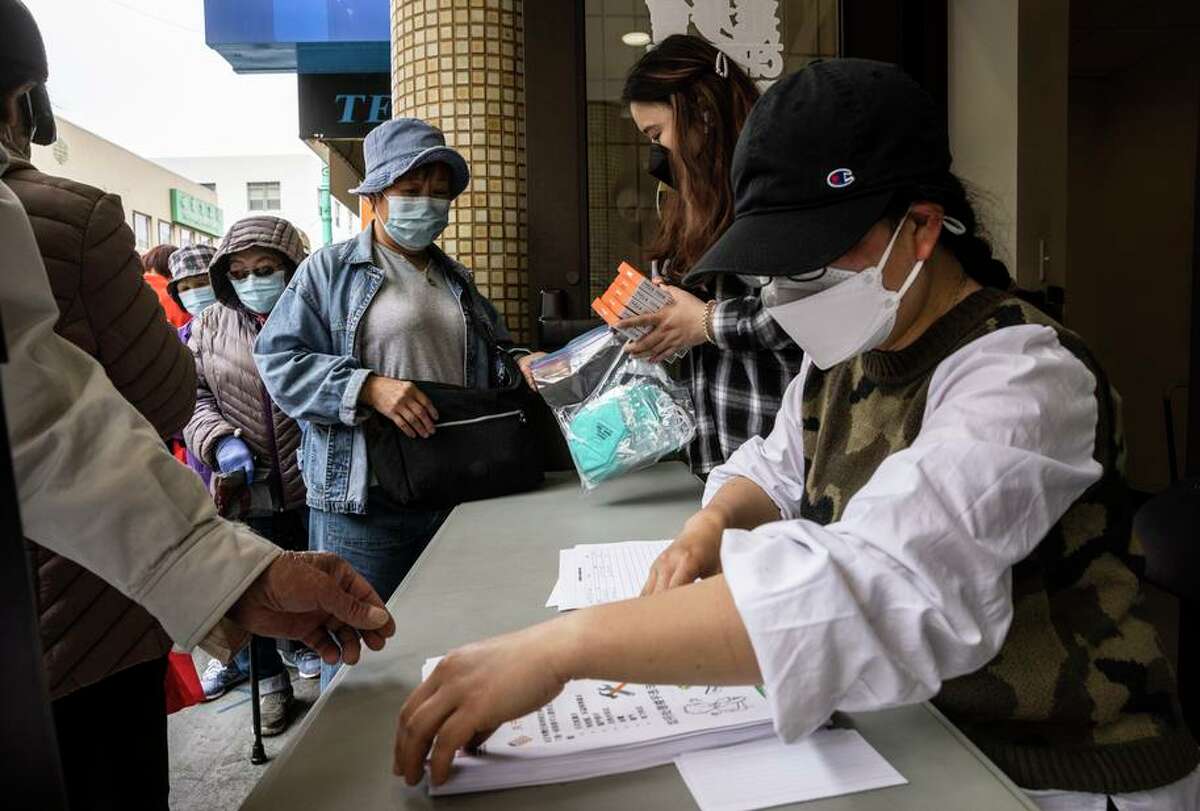

Yulian Luo works at a community event distributing personal protective equipment to SRO residents.

Stephen Lam / The ChronicleYulian Luo dashes up Pacific Avenue in San Francisco’s Chinatown to the home of an elderly woman who needs her help. Black baseball cap slung low, face mask and glasses covering her face, Luo meets the woman in her doorway and they chat.

Luo has many Cantonese-speaking residents to get to, fielding help requests involving poor housing conditions, pandemic concerns, better-paying work and fears about anti-Asian hate.

Today, Luo is a community organizer with the Chinese Progressive Association. Yet five years ago, when she left China, she thought she would work at a grocery store or a Chinese restaurant.

“I definitely had no idea I would be an activist in the U.S.,” Luo said in Cantonese, interpreted by KC Ho of the Chinese Progressive Association.

When Luo, her husband and their 6-year-old daughter arrived from China in 2016, they landed in a dilapidated single-room occupancy hotel. Her daughter cried every day.

“She would say to me, ‘Mom, let’s go back to China. I don’t like living here. It’s very bad conditions,’” Luo said.

Luo couldn’t immediately find work, so she enrolled in English classes at City College of San Francisco. There she met other SRO mothers who were similarly crammed with their families inside tiny rooms. Community organizers listened to them.

“They would help us and improve our living conditions, and that made me want to do it too,” Luo said.

She thought she could organize the residents in her building to more collegially share the four burners in the kitchen during busy dinner hours. She thought they could collectively demand that conditions in the shared bathrooms be improved. “I wondered, if we are all Chinese immigrants, why can’t we figure this out?” But it proved hard.

Yulian Luo, a community organizer with the Chinese Progressive Association, checks a package of personal protective equipment for SRO residents.

Stephen Lam/The Chronicle“It’s the system of the SRO that pits us against each other,” Luo said. “I realized what we need is more affordable housing.”

Her advocacy of low-income immigrant concerns landed Luo her first good job in America: community organizer for the Chinese Progressive Organization. She was thrilled to be working to better her community. Then the pandemic hit, and Chinatown became a ghost town.

Fears escalated inside SRO buildings. No one wanted to use shared bathrooms and kitchens, scared of contracting COVID. Despite her trepidation, Luo leaped into action. Her organization was raising money, and Luo was arranging with now-empty restaurants to cook hot meals that she and other organizers could distribute to families.

Her phone constantly pinged with requests for help. People needed face masks, hand sanitizer and basic goods that were sold out at supermarkets. While everyone else hunkered down, “I was so busy, (the requests) never stopped,” Luo said.

While she was out distributing food during the pandemic, Luo also began to encounter anti-Asian bigotry. “We had strangers, passersby, telling us to leave this country,” Luo said. “Fear shrouded us all; the hatred affected families.”

Shaken by the Atlanta spa shootings, Luo encouraged the families she worked with to come out to protest. She felt their voices needed to be heard. People trusted her, and they took to the streets in March 2021 demanding an end to hate against the Asian community.

As the pandemic wore on, the needs of the community became more dire, Luo said. She watched many low-wage, non-English-speaking workers lose jobs or get sick and not receive any paid time off to recover. The SRO residents struggled to survive, she said, and government assistance didn’t reach this community.

Luo is now part of a large coalition, the Bay Area Essential Workers Agenda, pushing elected officials to use some of the budget surplus to support SRO residents.

“We took care of this city during the pandemic, and now we don’t ask much — just to work with fair pay and basic things like health care,” Luo said.

She joined a protest on the steps of City Hall in early May and plans to bring more SRO residents to the next one.

Luo feels she has found her calling as a community organizer. The Chinese Progressive Organization trained her and pays her a fair wage with benefits. She wants that for others.

“This work is meaningful for me,” Luo said. “If we can find better jobs, we can move (from the SRO to) somewhere better.”

Justin Hoover, 40, executive director, Chinese Historical Society of America

Martial arts instructor Justin Hoover teaches 4-year-old Haoran Huang how to make a fist during a class in Chinatown.

Brontë Wittpenn / The ChronicleJustin Hoover does not call himself an activist.

Hoover is concerned about social inequality and its impact on San Francisco’s Chinatown, the place he visited frequently as a child with his Taiwanese mother and grandmother. Yet this martial artist, teacher and museum director has a different social change ethos, one that involves empowering young people to learn their cultural traditions while using the arts to build bridges with other marginalized communities.

Hoover admires famed political activist Angela Davis but channels martial arts legend Bruce Lee.

“Am I walking (in) protest marches? Rarely,” Hoover said. “But I don’t think that that’s the only way to combat the issues that you want to face down in society.”

His work in Chinatown became turbo-powered when the pandemic hit and Asian communities were targeted by hate and trapped in silos of marginalization. Pre-pandemic, children crammed in SROs had few outlets in Chinatown.

“There’s very few parks or educational resources that are free and accessible,” Hoover said. Kids were playing in unsafe conditions, he added. He launched youth martial arts classes embedded in a program called Peace Movements.

When COVID-19 locked everyone in their homes, Hoover moved his martial arts classes online, but SRO kids couldn’t participate because their buildings had poor internet. Hoover, who had started a job running the Chinese Historical Society of America, saw Chinatown become increasingly isolated, and he worried about the mental health of his community.

Kung fu was needed now more than ever, Hoover said.

“It’s not about punching and fighting,” he said. “It’s about standing and just meditating. It’s about breathing.”

He instructs his students to “pull your shoulders back, to open the lungs and to sit openly,” because “kids in school aren’t allowed to open their bodies,” Hoover said. The way schools train children to occupy a small space and type with their bodies hunched over a computer screen is an “oppression that we don’t even (notice) anymore,” Hoover said.

Justin Hoover teaches a martial arts class to kids in Chinatown: “It’s not about punching and fighting

“We bring in these philosophies of combating the pace of capitalism,” he said.

When things began to open up in late 2021, Hoover planned outdoor, in-person kung fu and art classes for Chinatown’s children. He also wanted his historical society to help make Chinatown less isolated and inaugurated a Bruce Lee exhibit upstairs and teen music, history and art classes downstairs.

“My work is all about how we empower communities to participate in arts and culture and tell their stories,” Hoover said. For too long, the diversity of the Chinese American story has not been told, and in telling their own story people are liberated, he added.

On a sunny February afternoon atop a basketball court in Chinatown, two dozen children shyly lined up for what would become their Sunday kung fu and art class. Hoover, masked and dressed in traditional black attire, mesmerized the children and parents with a saber-wielding demonstration.

Hoover sees this work as advancing the community that helped raise him.

“I wanted to pay that back and create programming that would activate Chinatown, that would empower a broader, diverse Asian-American and Chinese-American identity to feel welcome and to have ownership of this amazing area,” Hoover said. “So if you define that as activism, then yeah, I’d love to be called that.”

Editor’s note:

This story has been updated to include a co-founder of Stand With Asian Americans.

Deepa Fernandes is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: deepa.fernandes@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @deepafern

[ad_2]

Source link