Lyme bear center ‘graduates’ 137 yearlings — a new record

[ad_1]

Across the Upper Valley, adolescents brimming with the vigor of youth are getting ready to graduate from high school and set off from home to take their first steps into the great, wide world.

On Thursday, eight young denizens of Lyme also were preparing to “graduate” and leave the security of their home, likewise embarking — whether they are aware of it or not — into the broader world for adventures unknown.

The Lyme alums, all boasting shiny and healthy black fur coats thanks to plentiful winter meals of dog food and crimped corn, are among 137 American black bear yearlings being released this spring back into the wild by Kilham Bear Center, where they were brought as injured or orphaned and undernourished cubs last year.

Most of the cubs have lost their mothers — either due to being killed by firearms or being struck by vehicles — without whose protection and nursing they likely wouldn’t survive their first winter.

The cubs’ nine months at the sanctuary, where they emerge at around 18 months old and a strapping 110 or more pounds, gets them healthy enough for survival in the wild and roaming forests around northern New England.

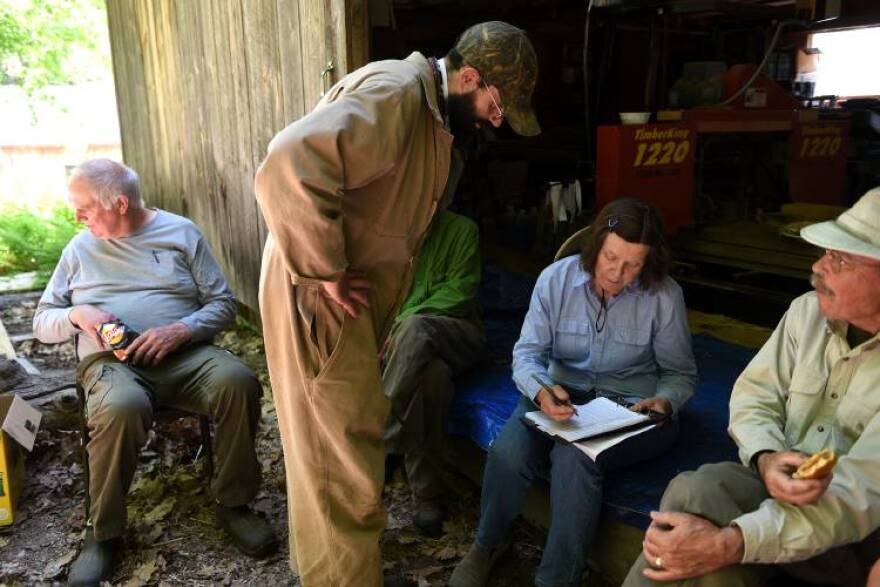

“It’s a record year. The highest was three years ago, when we had 79 bears,” said Center founder Ben Kilham, while watching a group of game wardens and wildlife biologists from the U.S. Forestry Service and Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department help round up, tranquilize, medically check, tag and prepare the bears for transport to undisclosed locations in Vermont on Thursday.

Eighteen months is also the age when the mother bear, in preparation for another breeding cycle, will force her yearling away to survive on its own. Kilham likened 18 months for a bear to the equivalent of 18 years for a human, the typical age when teens graduate from high school.

The 137 figure is extraordinarily high — “a typical year” involves 20 to 40 bears — and is “directly related to the natural food supply” in the bear’s habitat, Kilham said. The less supply of food — principally acorns, beach nuts and wild berries — the more bears will wander into populated areas in search of everything from bird feeders to chicken coops and garbage.

Jennifer Hauck

/

Valley News

Kilham Bear Center’s record number of bear intakes and releases this past year correlated with a “pronounced spike” in “bear conflicts” reported by Vermont Fish and Wildlife in 2022.

Last year, reported bear conflicts — interactions between bears and humans — jumped from 206 in May to 473 in June, exceeding the three-year average of 182 reports in May 2022 and 370 reports in June 2022, according to the state agency.

As of May 27 this year, there have been 136 reports, although that figure will surely grow as wardens file their monthly incident reports, which are not included in the monthly tally to date.

(Vermont Fish and Wildlife is urging people to keep their garbage bins inside until a few hours before pickup in order to reduce the risk of a conflict to human safety that might call for the bear to be killed, the agency warned in a news release this past week.)

The bears are brought to the center by state wildlife agencies in the Northeast, which “pick them up,” in Kilham’s words, after they’ve been reported to be straying along roads, into people’s yards or dumpster diving.

Forrest Hammond, a retired bear biologist with Vermont Fish and Wildlife, who along with West Newbury, Vt., wildlife biologist and veterinarian Walt Cottrell was on hand at the Center to assist with Thursday’s roundup and release of the yearlings, said there are 5,500 to 6,000 black bears in Vermont, although he stressed that is at best an estimate.

“Bears are difficult to census because they don’t run in herds,” Hammond pointed out.

Although bear populations are not estimated by town, a rule of thumb is “three-quarters to one bear per square mile,” he said.

State wildlife agencies like Vermont Fish and Wildlife like working with the Kilham Bear Center, according to Hammond, “because they have a good success rate (in caring for bear cubs and yearlings) and it’s a real service for state wildlife agencies,” which don’t have the funding to staff and operate their own bear sanctuary.

A different learner

Jennifer Hauck

/

Valley News

Kilham grew up in Lyme, the son of a Dartmouth Medical School professor, and graduated from Hanover High School and University of New Hampshire.

Keenly interested in wildlife and animal behavior since he was youth, Kilham nonetheless struggled with reading and school and did not know why until he was diagnosed with dyslexia as an adult.

But he was intellectually gifted in other ways, especially when it came to turning engineering concepts into practical applications with his hands.

In 1992, Kilham came into possession of two starving bear cubs and nursed them to health for release back into the woods.

That experience led to more bear cub rescues and eventually taking in dozens of cubs and then releasing them as yearlings annually, becoming a self-taught expert and published authority on American black bears along the way.

Five years ago, in 2015, at age 62, Kilham earned a doctorate in environment sciences from Drexel University in Philadelphia with a dissertation titled “The Social Behavior of American Black Bears.”

That was also the year that Kilham turned what had been what had become a fulltime avocation in “rehabilitating” bears into a 501c3 nonprofit with a mission to educate the public about black bears and study their cognitive and social behavior.

The move turbo-charged fundraising and ability to tap foundations for support.

The result is now plain to see: a new $550,000 reception center that includes a classroom with a big-screen TV showing live video feeds of dens with romping cubs was recently completed, and another 30-feet-by-42-feet timber frame cub barn — “which will cost more,” Kilham assures — is to begin construction this fall.

In the early years Kilham and his wife, Debbie, supported their bear rescue mission by her job as a retirement consultant and his trade as a custom gunsmith and gun designer, supplemented with income from hundreds of public lectures he has given around the country and two books on bears he authored.

They also have a small sugaring business with 1,300 maple tree taps on their 500-acre property in the hills of Lyme — the address of which they ask visitors to keep secret so as to prevent people from showing up uninvited to see and pet the cubs.

In fact, the Kilhams themselves no longer personally interact with the cubs, leaving that responsibility and privilege solely to Kilham’s nephew, Ethan Kilham, the center’s only full-time employee, in order to avoid habituating the cubs with humans. For many years Ben Kilham’s sister, Phoebe, helped out, but she now focuses on a GPS tracking project.

Nut crisis

Jennifer Hauck

/

Valley News

The center currently is at the peak of its releasing period, which runs from May to June, as wardens from different wildlife agencies show up at the sanctuary in Lyme on alternating days of the week. Vermont showed up on Thursday, New Hampshire was scheduled to follow on Friday, and this coming week the center expects to release four out of five days.

“I would hope by the end of June, we will have everyone out of here,” Kilham said.

Things slow down through the summer before the bulk of the next class of cubs begins rolling in around September.

The number of bears brought to the center historically goes up and down as their food supply fluctuates based on fecundity cycles of oak trees and beech trees which produce the nuts which are the food source of black bears. Wild berries are a third source.

Beech trees produce beech nuts every other year, while oak trees produce acorns four out of every five years. When those off-year cycles overlap — which historically has occurred every eight to 12 years — the food source for bears dries up, sending them on the hunt into human-occupied areas for food.

The center would get a corresponding increase in bear arrivals during those years.

But Kilham said in recent years the cycles of the overlapping nut tree off-years have been occurring more frequently. In addition, last summer’s drought “hammered the berry crop,” and together with the nut shortage devastated the bears’ food supply.

“There was no food in the forest,” he explained.

Notably, the shortening cycles of nut tree off-years and food shortages for bears have been tracking with climate change.

“It’s disconcerting,” he said.

The cubs have hearty appetites. A cub requires 8,000 calories per day during the summer — the equivalent of 14 Big Macs — and Kilham said the Center’s food bill is “$1,000 a clip at Tractor Supply.” (This past winter they were going nearly every week).

State wildlife wardens don’t want the public to know where they will be releasing the bears back into the forests, both to avoid creating fears that bears will be roaming peoples’ neighborhoods but also not to tip off hunters as to their possible location. All they will say is the bears, which are transported in custom-made steel cages, will be set free in a “large, contiguous forest” of federal or state property.

In any case, the yearlings won’t be in the area for long.

“They may stick around for 24 hours and then they’re off,” Hammond said.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

[ad_2]

Source link