A power disconnection crisis: In 31 states, utilities can shut off electricity in a heat wave

[ad_1]

By Sanya Carley and David Konisky

Millions of Americans have already been sweltering through heat waves this summer, and forecasters warn of hot months ahead. July 3 and 4, 2023, were two of the hottest days, and possibly the hottest, on satellite record globally.

For people who struggle to afford air conditioning, the rising need for cooling is a growing crisis.

An alarming number of Americans risk losing access to utility service altogether because they can’t pay their bills. Energy utility providers shut off electricity to at least 3 million customers in 2022 who had missed a bill payment. Over 30% of these disconnections happened in the three summer months, during a year that was the fifth hottest on record.

In some cases, the loss of service lasted for just a few hours. But in others, people went without electricity for days or weeks while scrambling to find enough money to restore service, often only to face disconnection again.

As researchers who study energy justice and energy insecurity, we believe the United States is in the midst of a disconnection crisis. We started tracking these disconnections utility by utility around the country, and we believe that the crisis will only get worse as the impacts of climate change become more widespread and more severe. In our view, it is time government agencies and utilities start treating household energy security as a national priority.

1 in 4 households face energy insecurity

Americans tend to think about the loss of electricity as something infrequent and temporary. For most, it is a rare inconvenience stemming from a heat wave or storm.

But for millions of U.S. households, the risk of losing power is a constant concern. According to the most recent data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, 1 in 4 American households experience some form of energy insecurity each year, with no appreciable improvement over the past decade.

For many low-income households, the risk of a power shut-off reoccurs month after month. In a recent study, we found that over the course of a single year, half of all households whose power was disconnected dealt with disconnections multiple times as they struggled to pay their bills.

Energy insecurity like this is especially common among low-income Americans, people of color, families with young children, individuals who rely on electronic medical devices or those living in poor housing conditions. During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that Black and Hispanic households were three and four times, respectively, more likely to lose service than white households.

Along with existing financial constraints, people are facing rising electricity rates in many areas, rising inflation and higher temperatures that require cooling. Some also face a history of redlining and poor city planning that has concentrated certain populations in less efficient homes. Taken together, the crisis is apparent.

Coping strategies can put health at risk

We have found that over half of all low-income households engage in some coping strategies, and most of them find they need multiple strategies at once.

They might leave the air conditioner off in summer, allowing the heat to reach uncomfortable and potentially unsafe temperatures to reduce costs. Or they might forgo food or medicine to pay their energy bills, or strategically pay down one bill rather than another, known as “bill balancing.” Others turn to payday loans that might help temporarily but ultimately put them in deeper debt. In our research, we have found that the most common coping strategies are also the most risky.

Once people fall behind on their bills, they are at risk of being disconnected by their utility providers.

The loss of critical energy services may mean that affected people cannot keep their homes cool – or warm during the winter months – or food refrigerated during any season. Shut-offs may mean that people with illnesses or disabilities cannot keep medicines refrigerated or medical devices charged. And during times of extreme cold or heat, the loss of energy utility services can have deadly consequences.

Where disconnection rates are highest

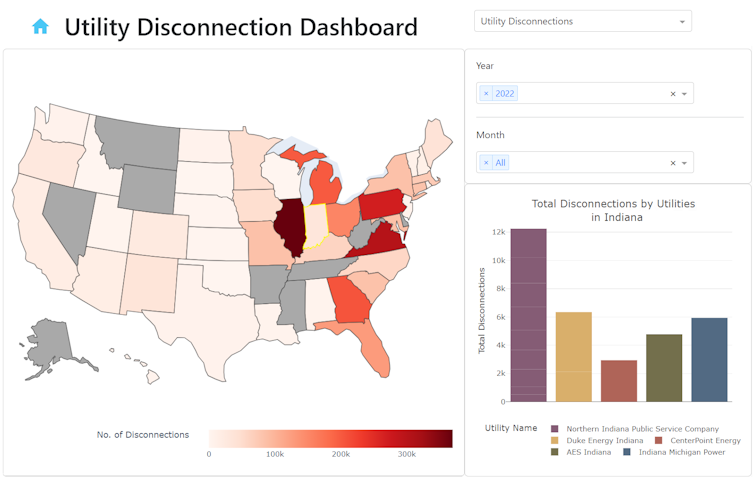

Our research team recently launched the Utility Disconnections Dashboard in which we track utility disconnections in all places where data is available.

In recent years, more states have required regulated utilities across the country to disclose the number of customers they disconnect. However, state regulations only apply to the utilities that they regulate. Public utilities and cooperatives, which serve over 20% of U.S. electricity customers, often aren’t covered. That leaves massive gaps in understanding of the full magnitude of the problem.

The data we do have reveals that disconnection rates soar during the summer months and are typically highest in the Southeast – the same states that were baking under a heat dome in June and July 2023.

Places with particularly high disconnection rates include Alabama, where the city of Dothan’s municipal utility has disconnected an average of 5% of its customers, and Florida, where the city of Tallahassee has a disconnection rate of over 4%.

Large investor-owned utilities in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and Indiana also top the charts in disconnections, with average rates near 1%.

Only 19 states restrict summer shut-offs

State public utility commissions place certain restrictions on the circumstances when utilities can disconnect customers, but summer heat is often overlooked.

All but a handful of states limit utilities from shutting off customers during winter months or on extremely cold days. Most have at least some medical exemptions.

Yet, the majority of states do not place any limits on utility disconnections during summer months or on very hot days. Only 19 states have such summer protections, which typically take the form of designating time periods or temperatures when customers cannot be disconnected from their service. We believe this is untenable in an era of climate change, as more parts of the country will increasingly experience excessive-heat days.

These state-level policies provide a baseline of protection. We learned during the COVID-19 pandemic that moratoriums that prohibit utility disconnections can alleviate energy insecurity by establishing a strong mandate against disconnections.

But these policies are highly variable across the country and particularly insufficient during hot summer months. Moreover, customer protections can be difficult for people to find and understand, since the language can be overly convoluted and confusing, placing additional an burden on already vulnerable Americans to discover for themselves how they can avoid losing service.

Better rules and a new mindset on right to energy

As we see it, the U.S. needs more robust customer protections, with states, if not the federal government, mandating better disclosure of when and where disconnections occur to identify any systemic biases.

Most of all, we believe Americans need a collective change in mindset about energy access. That should start with a principle that all people should have access to critical energy services and that utilities should only shut off service to customers as a last resort, especially during health-compromising weather events. The country cannot wait for deadly heat waves to prove how important it is to protect American households.![]()

Sanya Carley is presidential distinguished professor of energy policy and city planning at the University of Pennsylvania and David Konisky is the Lynton K. Caldwell professor at Indiana University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link