Analyzing Lori Lightfoot’s Legacy: A Combative Mayor Whose Reform Push Faltered Amid Pandemic Woes, Self-Inflicted Wounds | Chicago News

[ad_1]

Mayor Lori Lightfoot fields questions from the news media on Feb. 7, 2023, after the WTTW News mayoral forum. (Michael Izquierdo / WTTW News)

Mayor Lori Lightfoot fields questions from the news media on Feb. 7, 2023, after the WTTW News mayoral forum. (Michael Izquierdo / WTTW News)

When Lori Lightfoot looks back on her single term as mayor of Chicago, she may remember Feb. 14, 2020, as her last normal day.

As a bitter wind iced the city, Lightfoot relished the chance to confront the well-heeled crowd gathered for a luncheon hosted by the City Club of Chicago about the deep-seated problems facing Chicago.

“Poverty is killing us,” said Lightfoot, blaming systemic racism for forcing tens of thousands of Chicagoans to struggle daily to find food, clothing and shelter. “Literally and figuratively killing us. All of us.”

Lightfoot urged the movers and shakers in Chicago’s business, government and philanthropic communities to act immediately.

“Am I making you uncomfortable?” Lightfoot said. “I mean to.”

But four weeks after that speech, the COVID-19 pandemic swept into Chicago, upending Lightfoot’s tenure as mayor of the nation’s third largest city and forcing her to jettison much of the agenda she hoped would earn her a place among Chicago’s transformational leaders.

Lightfoot ends her historic term as both the first Black woman and first out gay person to serve as Chicago’s mayor on Monday with few completed and lasting accomplishments, leaving Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson to govern a badly fractured city still struggling to recover from the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic that served to spotlight Chicago’s deeply entrenched problems.

In the weeks leading up to her departure, Lightfoot has insisted that she is leaving Johnson a city on firm financial footing thanks to the seeds of progress she planted as part of her efforts to make Chicago a more equitable place to live.

Lightfoot declined to answer questions from WTTW News about her legacy as mayor of Chicago. She has held just one formal news conference since finishing third on Feb. 28, failing to advance to the runoff election.

“If there’s a legacy, I hope it’s a legacy of fighting on behalf of ordinary residents in this city to free up our city government to do the right thing in neighborhoods and for people that desperately needed it the most,” Lightfoot told Craig Dellimore, host of WBBM Radio’s At Issue program on April 30. “I leave office with my head held high, knowing that every single day I made a lot of tough but necessary decisions in some of the difficult, challenging circumstances that any mayor in the history of this city has faced. I feel very comfortable with the way in which we governed.”

Lightfoot said her bid to be the first woman reelected Chicago mayor was doomed by the refusal of the news media to cover her fairly as well as the lingering “anger, frustration and fear” triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, Lightfoot told WLS-TV’s Craig Wall.

“So, for me, the biggest challenge wasn’t some particular person’s name on the ballot,” Lightfoot said to Wall. “The biggest challenge was breaking through what I call that ‘anger bubble.’”

Lightfoot also said racism and sexism contributed to her loss, doubling down on her oft-stated belief that she was not measured with the same yardstick applied to former Mayors Rahm Emanuel and Richard M. Daley.

“I’m a Black queer woman,” Lightfoot told WBBM Radio. “I have always known my entire adult life that there is a different set of rules and standards by which I will be judged. That is not a surprise.”

In her closing pitch to voters before the February election, Lightfoot touted Chicago’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic as the best of any big city, and pledged to finish what she started before her agenda was derailed by a once-in-a-generation global disaster. Lightfoot also made an explicitly race-based appeal, telling Black voters she was their best hope to keep control of City Hall.

The closest Lightfoot came to acknowledging that she was responsible for her own faltering political fortunes came in a December television ad.

“I’m not gonna sit here and tell you we did everything perfectly,” Lightfoot said. “We haven’t, but we’ve tried our darndest to make sure that we got it right and when we haven’t, you pick yourself up and you listen and you’re humble and you learn from your mistakes.”

But after the ad aired, Lightfoot declined to answer a question from WTTW News about what specific mistakes she made as mayor and what she had learned as a result.

“I broke a lot of eggs and to be blunt I pissed a lot of people off, but I did it for the right reasons and I did it on behalf of people who felt like they were locked out of resources and locked out of City Hall because City Hall in their perception and the resource allocations were controlled by a small, clouted few that hurt the rest of Chicagoans,” Lightfoot told WBBM Radio.

Lightfoot finished with just 16.8% of the vote.

Video: Mayor Lori Lightfoot delivers her inaugural address on May 20, 2019. (WTTW News)

A Short-Lived Mandate

In 2019, Lightfoot coasted to the fifth floor of City Hall with approximately 75% of the vote in the April runoff, claiming a mandate to end the corruption personified by indicted Ald. Ed Burke (14th Ward).

During her inaugural address, Lightfoot brought the crowd to its feet when she vowed to put an end to the sense that putting Chicago government and integrity in the same sentence is an oxymoron at best — or a joke at worst.

As the cheers shook the floor at the Wintrust Arena, Lightfoot turned to look at the alderpeople in attendance, a slight smile on her face, and gestured that they should applaud, too.

The gesture poisoned Lightfoot’s relationship with many on the Chicago City Council, whose members bristled at her decision to treat them not as equals, but as foils to be used to burnish her credentials as a champion of good-government reforms.

Less than two hours later, Lightfoot signed an executive order that declared an end to aldermanic prerogative, blaming it for not only breeding corruption but also for creating and reinforcing the rules that have made Chicago a hyper-segregated city rife with racism and gentrification.

Despite her ringing promises, Lightfoot never proposed overhauling the city’s zoning code, the ultimate authority on what can be built on each street in Chicago — and who gets to change those standards — leaving the heart of aldermanic prerogative untouched, along with the structural forces undergirding the city’s inequity.

Lightfoot will leave office with the largely unwritten, decades-old practice giving alderpeople a veto over ward issues still intact.

Lightfoot also broke a campaign promise to create an independent commission to draw a ward map based on the 2020 census that reflected neighborhood boundaries and not gerrymandered borders.

Instead, the map that will be in place for the next decade was drawn the same way it has always been – behind closed doors by incumbent alderpeople, who picked their own voters, punished their enemies and boosted their allies.

The City Council did twice overhaul Chicago’s ethics laws with Lightfoot’s support. Those changes gave the inspector general the authority to investigate alderpeople and committees; hiked fines for violations from $2,000 to $20,000 and banned members of the City Council from working as property tax attorneys — a provision that was aimed squarely at Burke.

But Lightfoot spent much of her time in office at odds with Inspector General Joseph Ferguson, and declined to appoint the watchdog to another term. She also had a tense relationship with Ferguson’s successor, Inspector General Deborah Witzburg.

Shortly after he left office, Ferguson told WTTW News that not only had Lightfoot failed to live up to promises on reform and transparency, things were actually worse during her administration than under Emanuel.

Lightfoot did make good on promises to focus the city’s economic development efforts on the city’s South and West sides, which have been devastated by decades of disinvestment and deeply rooted poverty.

Lightfoot’s Invest South/West initiative promised to spend $750 million to address the fundamental problems that have tormented those communities for decades, including a lack of jobs and few inviting places to shop, gather and have fun.

But the initiative — complicated by the pandemic and the unrest that swept the city in 2020 — has so far not resulted in significant overall changes, and its future in a Johnson administration is unclear.

Challenges, Multiplied

Shortly after taking office, Lightfoot was confronted with a budget deficit of $838 million, which she called “staggeringly large.” The figure prompted her to immediately drop plans to ask state lawmakers to hike the Real Estate Transfer Tax to fund efforts to reduce homelessness and to create a Department of the Environment — two key campaign promises embraced by progressive groups and voters.

As she worked to craft her first spending plan and bridge the gap, Lightfoot confronted another challenge: contract negotiations with the Chicago Teachers Union, which had supported her rival in the runoff, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle.

The Chicago Teachers Union and SEIU Local 73 hold a massive demonstration in the Loop on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2019 — day five of the Chicago teachers strike. (WTTW News)

The Chicago Teachers Union and SEIU Local 73 hold a massive demonstration in the Loop on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2019 — day five of the Chicago teachers strike. (WTTW News)

After an 11-day strike, the longest since 1987, schools reopened, but Lightfoot’s soured relationship with the city’s most powerful progressive union never recovered.

The most contentious part of the labor dispute was not pay and benefits for teachers and staff members, but union demands that the city do more to ensure that students and their families had affordable and safe places to live, access to mental health care and smaller class sizes.

Lightfoot fought the union on those issues, even though she ran for mayor on a platform that vowed to address the city’s affordable housing gap of nearly 120,000 homes and promised to reopen the publicly run mental-health clinics closed by Emanuel in 2011.

Once she took office, Lightfoot took a different approach to mental health, led by Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Allison Arwady. Instead of reopening the clinics, the city turned to nonprofit organizations to deliver care to those who did not have private insurance or the ability to pay out of pocket.

While Lightfoot said that push showed “tremendous results,” her refusal to reopen the mental health clinics became another broken campaign promise relied on by progressive voters and groups.

Lightfoot won plaudits from progressives when she tackled affordable housing in Chicago, tapping Marisa Novara, an outspoken advocate for policies designed to ensure every Chicagoan had access to safe housing at a reasonable cost, to lead a newly reconstituted Department of Housing.

Novara swiftly changed the way the city awarded tax credits to fund the creation of homes set aside for low- and moderate-income residents. She also led the push to revamp the city’s most powerful tool to create affordable housing by requiring developers who get special permission from the city or a subsidy to set aside units for low- and moderate-income Chicagoans or pay higher fees.

The only specific proposal Lightfoot unveiled in her 2019 speech vowing to end generational poverty in Chicago to be enshrined into law ensured long-term renters would have a notice of 90 days before they could be evicted without cause, rather than just 30 days.

Those changes, along with others including the legalization of coach houses and granny flats, won plaudits from housing advocates, a lone bright spot for the mayor among those on the left.

But support from those groups completely dissipated after Lightfoot blocked a hearing on a proposal to ask voters during the February 2023 election to hike taxes on the sales of properties worth $1 million or more in an effort to fight homelessness in Chicago.

Exercising her power like an old-school machine politician, Lightfoot demanded that her allies refuse to attend the hearing — even though several were just down the hall at the time.

The mayor’s actions were particularly galling for housing advocates because she campaigned on a promise nearly identical to the proposal known as Bring Chicago Home, only to reverse course after taking office.

That about-face was one of many campaign promises Lightfoot broke, including support for an elected school board as well as a proposal to give a board of Chicagoans the final say on policy for the Chicago Police Department.

Lightfoot also promised to bring back the city’s Department of Environment, only to actively fight the plan during the debate over the city’s 2023 budget.

Despite a campaign platform that vowed to tackle environmental racism, Lightfoot angered activists working to reduce air and water pollution on the South and West sides by allowing the demolition of a smokestack at the former Crawford Power Plant in Little Village. The botched implosion sent a plume of dust over the primarily Mexican American neighborhood — even though a report by the city’s watchdog found city officials warned it was going to be “cataclysmic.”

As part of a separate investigation, federal officials determined Lightfoot’s administration violated the civil rights of Black and Latino Chicagoans by allowing a metal shredding and recycling operation to move from the North Side to the Southeast Side.

Amid the federal probe, Lightfoot’s administration declined to issue the final permit the shredder needs to start operations – a decision the firm is challenging.

By the time Lightfoot launched her reelection campaign, she had spent much of her time in office at loggerheads with many of Chicago’s progressive political organizations, all but ensuring they would support someone else in 2023.

That energy coalesced behind Johnson, a Cook County commissioner and organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union, propelling him into the mayor’s office with the overwhelming backing of Black voters in the runoff election.

People wait in line for COVID-19 tests in Chicago. (WTTW News)

People wait in line for COVID-19 tests in Chicago. (WTTW News)

A Global Pandemic Comes Home

For a brief period of time, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Lightfoot’s response, offered her an opportunity to reboot her tenure.

As scared Chicagoans huddled in their homes, Lightfoot’s brusque warnings about the deadly virus became fodder for internet memes and jokes.

Lightfoot’s grim-faced image, captured by Ashlee Rezin, of the Chicago Sun-Times, was Photoshopped onto landmarks across the city, warning people to stay home — or risk infecting themselves or their loved ones with COVID-19.

Lightfoot leaned into the memes, releasing a video showing her baking and learning to play guitar while under lockdown and dressing up as a “rona destroyer” in advance of Halloween 2020. That brought her national attention, as terrified Americans searched for leadership during the economic catastrophe brought on by the shutdown orders.

But the focus on the memes and videos and tweets obscured Lightfoot’s serious disagreements with Gov. J.B. Pritzker who in the early days of the pandemic moved to shut down Chicago’s bars and restaurants and then Chicago’s schools over Lightfoot’s strenuous objections.

That conflict alienated Lightfoot and Pritzker, complicating efforts by city and state officials to respond to the virus, which was wreaking havoc in Chicago’s Black and Latino communities.

Lightfoot appeared with newly minted Chicago Police Supt. David Brown to warn those determined to defy the stay-at-home order by hosting parties would be arrested and charged. After a news conference, Lightfoot disrupted a nearby pick-up basketball game, telling the Black teens to go home and stay there — a move that was greeted with howls of outrage by those concerned the pandemic would prompt a crackdown on teens living in already struggling neighborhoods and accusations of disparate treatment.

By February 2021, the City Council’s Progressive Caucus was in full revolt over Lightfoot’s decision to use $281.5 million in COVID-19 federal relief funds to cover the cost of salaries and benefits for Chicago Police Department officers.

Lightfoot pushed that spending through, but faced a fusillade of criticism from progressive politicians who argued that money would have been better used to send direct aid to people and businesses struggling to stay afloat amid the economic wreckage caused by the pandemic.

Furious progressive organizations used Lightfoot’s decision to prioritize funding for police officers over residents to cast her as blindly supportive of police at a time when much of the Democratic political establishment was consumed with efforts to rethink public safety.

Lightfoot called the criticism “dumb.”

Lightfoot also clashed with the Chicago Teachers Union as a fresh wave of the COVID-19 virus inundated Chicago in December 2021, this one driven by the more transmissible omicron variant.

The mayor resisted demands to reach a safety agreement with the union that would set the rules for when schools would return to remote learning amid a surge of cases at each school and require frequent testing of students.

After talks broke down, the union voted not to return to in-person teaching on Jan. 5, 2022. That prompted Lightfoot to lock them out, triggering a work stoppage that lasted five days before an agreement was reached.

Relations between the mayor and union leaders worsened, with Lightfoot accusing teachers of abandoning their students while making Chicago a “laughingstock” and then-union Vice President Stacy Davis Gates calling Lightfoot “unfit to lead” Chicago.

Davis Gates, who is now president of the Chicago Teachers Union, introduced Johnson as he took the stage to deliver his election night victory speech.

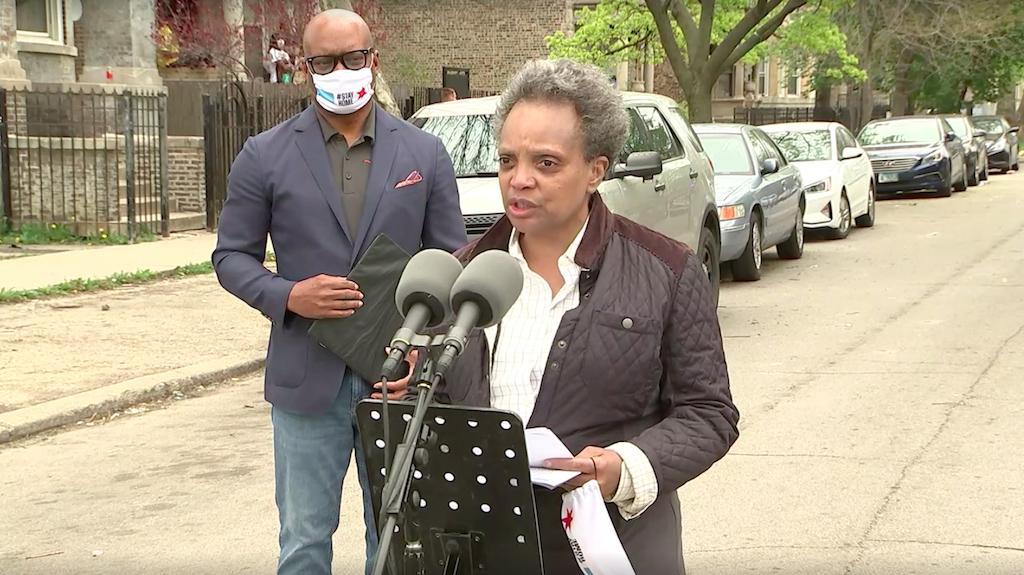

A screenshot from a May 2, 2020, news conference with Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown in the city’s West Garfield Park neighborhood after 49 people were shot over that holiday weekend. (Chicago Mayor’s Office)

A screenshot from a May 2, 2020, news conference with Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown in the city’s West Garfield Park neighborhood after 49 people were shot over that holiday weekend. (Chicago Mayor’s Office)

Public Safety, In Crisis

In addition to blowing a $2 billion hole in the city’s 2020 and 2021 budgets, the COVID-19 pandemic sparked a surge of crime and violence that has yet to recede.

More than 800 people were killed in 2021, making it the most violent year in Chicago since the mid-1990s. While homicides dropped approximately 14% in 2022, as compared with 2021, the number of people killed in Chicago rose nearly 38% from 2019 to 2022, according to Chicago Police Department data.

Those harsh statistics defined the 2023 mayoral race. While former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas blasted Lightfoot as not tough enough on crime, Johnson vowed to take a more “holistic” approach to public safety by addressing the root causes of crime and violence by increasing funding for youth employment programs and expanding access to mental health services.

During the campaign, Lightfoot attempted to paint both Vallas and Johnson as too extreme, while blaming Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx and Cook County Chief Judge Tim Evans for not jailing those she believed posed a threat to Chicagoans before their trials.

As crime remained stubbornly high, Lightfoot declined to shift her strategy — and steadfastly supported Chicago Police Supt. David Brown, her handpicked choice to serve as the city’s top cop. Both Vallas and Johnson vowed to fire Brown, and he quit less than 24 hours after they advanced to the runoff.

Ultimately, Lightfoot’s already narrow path to a second term proved unnavigable.

Lightfoot told WBBM Radio after her loss that the city’s view of crime is largely the news media’s fault. The city made meaningful progress in reducing violent crimes in 2022, but “most residents of the city don’t know it because that wasn’t something that the media reported and then when we started to make the progress many in the media frankly changed the goalposts,” Lightfoot said, adding that the “24-hour news cycle and the sensationalization of every issue didn’t help.”

Lightfoot rarely acknowledges that while crime may have dropped in 2022 as compared with 2021, it remains much higher than it was when she took office.

Promises of Reform, Unfulfilled

Lightfoot also fell far short of her promise to swiftly implement the court order requiring the Chicago Police Department to change the way it trains, supervises and disciplines officers.

That order was issued after a 2017 federal investigation found officers routinely violated the constitutional rights of Black and Latino Chicagoans. Though the order is now more than four years old, the city is in full compliance with just 3% of its requirements, according to data released by the Chicago Police Department.

There has also been no end to the high-profile police misconduct scandals that have roiled the city, with settlements costing taxpayers nearly $100 million annually.

A national firestorm erupted in December 2020 after CBS 2-TV aired video of officers mistakenly raiding the home of Anjanette Young, a social worker, in February 2019 before Lightfoot took office. Footage captured by the officers’ body-worn cameras showed seven male police officers handcuffing a naked Young, who told them 43 times that they were in the wrong home and begged them to let her get dressed.

While Lightfoot first told reporters she first learned of the incident from media reports, emails released by the mayor’s office show she was briefed on the botched raid in November 2019 as officials fought Young’s demands for video footage of the raid. While a probe ordered by Lightfoot cleared her of wrongdoing, she declined to release the results of the full probe conducted by the city’s inspector general.

Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward), left, speaks with Mayor Lori Lightfoot at a City Council meeting Wednesday, June 23, 2021. (WTTW News)

Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward), left, speaks with Mayor Lori Lightfoot at a City Council meeting Wednesday, June 23, 2021. (WTTW News)

Lightfoot’s relations with City Council members reached perhaps an all-time low when Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward) blocked a vote on Lightfoot’s pick to serve as the city’s top lawyer because attorneys for the city had refused to settle the lawsuit she filed.

Enraged, Lightfoot left the rostrum and confronted Taylor. As flashes popped and cameras zoomed in, Lightfoot and Taylor argued for several minutes, with Taylor growing animated as Lightfoot seethed with anger and frustration.

In addition, Lightfoot faced widespread condemnation when police officers shot and killed 13-year-old Adam Toledo on March 29, 2021, and 22-year-old Anthony Alvarez on March 31, 2021. Both killings triggered widespread protests and demands for change.

But for many, Lightfoot’s public safety legacy will also be defined by her response to the unrest that hurtled across the city after a Minneapolis Police Officer murdered George Floyd in front of a crowd of outraged people and a teen girl holding a cell phone aloft while recording.

Lightfoot raised all but one of the bridges into and out of downtown for the first time in modern Chicago history while imposing a curfew, shutting down the CTA and calling in the Illinois National Guard for the first time since the late 1960s.

The image of the raised bridges became a symbol for many of Lightfoot’s decision to prioritize the safety of the wealthy — and White — residents who lived downtown along with the businesses and stores in the Loop, while leaving Black and Latino Chicagoans to fend for themselves on the South and West sides.

While the bridges were raised, members of the Chicago City Council pleaded with Lightfoot to protect their communities during a conference call. Several alderpeople told Lightfoot she made business corridors on the South and West sides an “easy target” for looters and criminals because they “did not have the same level of protection.”

Lightfoot defended her response, telling the City Council members their criticism “offends me deeply, personally, in part because it is simply not so.”

However, a probe by the inspector general’s office found Lightfoot and police brass botched nearly every aspect of their response to the protests and unrest triggered by Floyd’s murder.

A Bright Spot: Chicago’s Finances

Lightfoot’s biggest victory in Springfield was convincing state lawmakers to green light a casino for Chicago, and change the rules at her request. City officials are counting a casino to boost the local economy and funnel approximately $200 million into its police and fire pension funds, significantly easing the pressure on the city’s finances, while creating thousands of jobs and drawing tourists — and their fat wallets.

But it will be Johnson who will preside over the first pull of a slot machine in Chicago, not Lightfoot.

Lightfoot has not shied away from claiming credit for leaving Chicago in a much better financial condition than she found it, promising Johnson a historically small budget deficit in 2024.

Lightfoot’s decision to pull the curtain back on the city’s financial forecast months earlier than usual will make it more difficult to follow the path set by Lightfoot and Emanuel, who blamed their predecessors for the financial mess they found after taking office.

Whether the projected surplus materializes once Johnson takes office, Lightfoot can claim credit for climbing the so-called pension ramp by complying with the terms of a state law designed to force the city’s pensions to be funded at a 90% level by 2045.

Between 2019 and 2023, the city of Chicago paid nearly $1 billion more to its four pension funds — without adding to the city’s already massive debt burden or cutting services, an accomplishment many financial experts considered impossible.

After touting her financial stewardship of the city, Lightfoot has offered the man who ousted her from the fifth floor of City Hall just one piece of public advice.

“Don’t screw it up,” Lightfoot said, in one of her last appearances as Chicago’s 56th mayor.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]

[ad_2]

Source link