Development and validation of the ADHD Symptom and Side Effect Tracking – Baseline Scale (ASSET-BS): a novel short screening measure for ADHD in clinical populations | BMC Psychiatry

[ad_1]

Study 1

Results of the EFA identified three items that did not align with factor loadings appropriately. These included excessive talking, sleep quality, and brain fog. Specifically, the item excessive talking failed to achieve a 0.40 communality, the item sleep quality failed to load onto a factor at a 0.40 level, and brain fog loaded onto both two factors over the 0.32 cut-off. After removing excessive talking, sleep quality, and brain fog, the EFA identified a two-factor model explaining 68.40% of variance between participants. The pattern matrix demonstrated loadings of six items onto one factor and the other four items onto a second factor. We reviewed the items belonging to each factor for conceptual fit with ADHD DSM 5 criteria. We named the first factor Inattentive, as the resultant items correspond conceptually with an attention deficit aspect of ADHD per criteria in the DSM 5. We named factor two Hyperactivity and Impulsivity due to alignment with DSM-5 criteria concerning behavioral and emotional dysregulation in an ADHD clinical presentation.

Table 1 displays the EFA-identified factor structure of the ASSET-BS. The two-factor model’s goodness of fit was calculated as χ2(26) = 85.69, p < 0.001. The factors correlated with each other significantly, r (155) = 0.66, p < 0.001, and the magnitude of the correlation coefficient indicated good convergent validity between the subscales.

Internal reliability for the 10-item ASSET-BS was α = 0.91. Internal reliability for the Inattentive subscale was α = 0.91, and the Hyperactivity and Impulsivity subscale’s internal reliability was α = 0.81. An independent-sample t-test found that participants who self-reported carrying a current ADHD diagnosis (n = 41) scored significantly higher on the ASSET-BS than participants who self-reported not carrying an ADHD diagnosis (n = 111), t (150) = 8.745, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.55.

Study 2

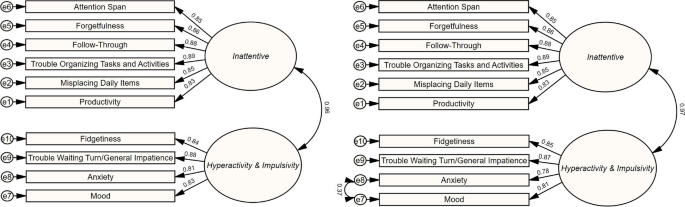

Internal reliability for the 10 ASSET-BS items was α = 0.961. Little’s MCAR test indicated that any missing values were at random, χ2 (79) = 84.17, p = 0.324. A total of 0.66% (33/5910) of all possible item answers were missing. Missing item answers were imputed with a maximum likelihood method to facilitate an effective structural equation model analysis in IBM’s AMOS software package. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) performed via a structural equation model analysis of the two-factor item-loading model discovered in Study 1 (Theoretical Model) found strong standardized regression weights for factor loadings of all items onto their hypothesized factors. In assessing model fit, the analysis supported a finding of an acceptable-fitting model according to some indices (CFI for comparative fit, and the index PNFI indicated good model parsimony), but the RMSEA index was slightly elevated into a range indicating a degree of fit between a poor and acceptable fitting model, χ2 (34) = 180.19, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.085 (90% CI of 0.073 and 0.098), and PNFI = 0.731. Additionally, the covariance between the latent factors (β = 0.96), was strong enough to raise a question of whether a one-factor model may be the optimal way to configure the items.

Inspecting the standardized residual matrix revealed no significant measurement error was introduced by any item. The modification indices identified that if the error terms of the items anxiety and mood were allowed to covary, model fit may improve noticeably. Conceptual support for allowing these items to covary was that both items load onto the same factor, and anxiety and mood are rationally highly related in that changes in one construct could logically coincide to a high degree with a change in the other. A structural equation model analysis of an adjusted model adopting covariance between anxiety and mood (Modified Model), found improved global and comparative fit statistics over the Theoretical Model with a slight reduction in parsimony, χ2 (33) = 110.39, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.063 (90% CI of 0.054 and 0.076) and PNFI = 0.718. Figure 1 displays the path diagrams for both the Theoretical Model and Modified Model, along with the standardized regression weights of the identified interrelationships between observed and unobserved variables.

Next, given the strong level of covariance calculated between the two latent variables, we compared a hypothesized one-factor model of the ASSET-BS to the Modified Model. The one-factor model achieved minimal differences in fit statistics in comparison to the Modified Model’s fit statistics, χ2 (34) = 126.37, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.983, RMSEA = 0.068 (90% CI of 0.55 and 0.081) and PNFI = 0.739. As the two-factor model was identified in Study One’s findings, had conceptual alignment with the DSM-5’s two-dimensional ADHD nomenclature, and the one-factor model failed to unambiguously improve goodness of fit, we opted to retain the two-factor model as represented in Fig. 1.

To allow for future administrations of the ASSET-BS to capture the Modified Model’s improvements in measurement accuracy, factor score coefficients were calculated and are presented in Table 2. Item-level scoring coefficients should guide scoring calculations in the following steps: first determine subscale scores via a sum of the subscale’s weighted item-level scores, multiply the subscale scores by the subscale-level scoring coefficients, and then sum the weighted subscale scores together to arrive at a total factor-weighted ASSET-BS score. The scoring coefficients are adjusted so that the overall ASSET-BS factor score is a continuous integer greater than or equal to 1 and lesser than or equal to 6. A paper version of this scale including the factor-weighted scoring calculation is reproduced in Supplement 1: Appendix A.

Covariate analysis

The demographic variables were re-coded as categorical (race, gender, geographic area of the United States, and urban or rural) or continuous (age and level of education). Of the possible covariate variables, initial correlation (continuous variables) and ANOVA (categorical variables) analyses, found that gender may possibly impact ASSET-BS scores significantly with a non-negligible effect size, F (1) = 19.10, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.37. As non-cisgender participants made up a very small portion of the sample, only scores from participants who identified as cis-gender were entered into an ANOVA to identify differences in mean ASSET-BS scores based on gender (cis-women: M = 3.23, SD = 1.52; cis-men: M = 3.78, SD = 1.47).

To test whether gender affected the CFA in terms of either factor loading or model fit, we compared CFA results via separate structural equation model analyses, splitting the sample by gender groups (cis-gender male and cis-gender female). For the two groups analyzed, all items loaded onto their hypothesized latent variables without noticeable variation from the CFA tests of the Theoretical Model and Modified Model. The model’s fit statistics for the cis-gender women group were χ2 (33) = 105.35, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.084 (90% CI of 0.66 to 0.102) and PNFI = 0.708. The model’s fit statistics for the cis-gender men group were χ2 (33) = 68.33, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.063 (90% CI of 0.41 and 0.084) and PNFI = 0.714. For the cis-gender women group, covarying the error terms of the executive functioning items productivity and misplacing daily items improved model fit χ2 (32) = 87.63, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.981, RMSEA = 0.075 (90% CI of 0.56 to 0.094) and PNFI = 0.691, but had negligible effect on model fit when applied to the cis-gender men group, χ2 (32) = 65.71, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.987, RMSEA = 0.062 (90% CI of 0.41 to 0.084) and PNFI = 0.693. Recalculating scores for cis-gender women participants using adjusted factor weights (reproduced in Supplement 2: Appendix B) to reflect the allowance of covariance between productivity and misplacing daily items negligibly reduced the effect size of gender on ASSET-BS scores, falling from Cohen’s d = 0.37 to Cohen’s d = 0.35.

Study 3

Internal reliability of the ten ASSET-BS items was ⍺ = 0.899. In this sample, Gender was found to have a small but significant correlation with ASSET-BS scores r (143) = 0.232, p = 0.005. The cis-gender men’s mean ASSET-BS score was 3.47, SD = 1.23 and the cis-gender women’s mean ASSET-BS score was 4.04, SD = 1.10. A binary logistic regression analysis found that gender accounted for 5.2% of the variance between participants in ASSET-BS scores, Cox & Snell R2 = 0.052, χ2 (1) = 7.07, p = 0.006. Adjusting the women’s ASSET-BS scores by using Study 2’s alternative factor weighting for women had no impact on the effect size of gender on difference in mean ASSET-BS scores.

Discriminant validity

Using the classification criteria outlined in the Analyses section, the three-author team classified 30 participants as ADHD positive, 93 as ADHD negative, and 12 participants were excluded from discriminant validity analyses due to internal-validity flags contained in their CAARS results reports.

Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics of the ADHD positive and negative groups in relation to the ADHD-relevant measures that were administered. In this sample, the ADHD-positive group self-reported a strikingly high level of symptom severity compared to more conservative estimates assessed by the CAARS-observer report scales; however, the ADHD positive group’s scores had lower standard deviation values than the ADHD negative group.

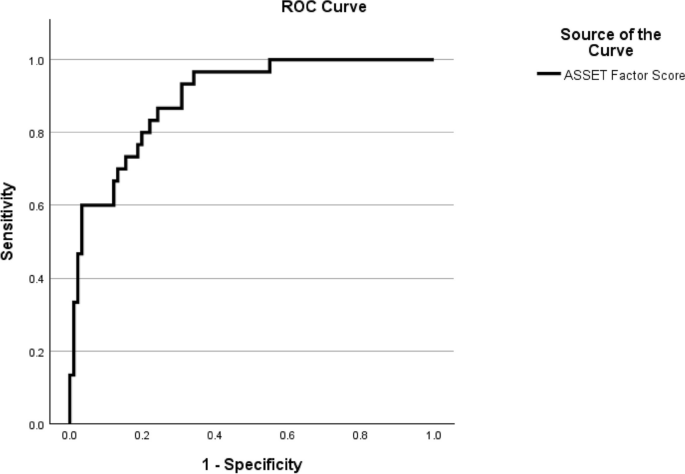

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of the ASSET-BS calculated an AUC coefficient of 0.895, (95% CI = 0.835 to 0.954), and a Gini index coefficient of 0.789. An ASSET-BS factor score of 4.04 achieved 96.7% sensitivity and 65.9% specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) = 47.54%, negative predictive value (NPV) = 98.39%. To better balance sensitivity and specificity, a score of 4.40 achieved 80.0% sensitivity and 80.2% specificity, PPV = 57.14%, NPV = 92.60%. Figure 2 displays the graph of the ROC curve line.

Convergent and divergent validity

The ASSET-BS strongly correlated with published self-report measures of ADHD, specifically the Brown EF/A Index Score r (131) = 0.76, p < 0.001, the CAARS Self-Report ADHD Index, r (131) = 0.71, p < 0.001, and the CAARS Self-Report DSM-5 ADHD Symptoms Index, r (131) = 0.68, p < 0.001. The ASSET-BS moderately correlated with the CAARS Observer-Report ADHD Index (r (104) = 0.49, p < 0.001), as well as the CAARS Observer-Report ADHD Symptoms Score, r (104) = 0.45, p < 0.001. The correlation coefficients of the relationships between the ASSET-BS and the CAARS Observer-Report scores were similar in magnitude to the correlation coefficients describing the relationship between the CAARS Self-Report ADHD Index and the CAARS Observer-Report ADHD Index, r (107) = 0.55, p < 0.001, and the CAARS Observer-Report DSM 5 Symptoms Score, r (107) = 0.51, p < 0.001.

To assess divergent validity, correlations between the ASSET-BS and measures for sleepiness, depression and OCD were calculated. The ASSET-BS moderately correlated with the PHQ 9, r (143) = 0.57, p < 0.001. It weakly correlated with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), r (143) = 0.22, p = 0.009, and had no significant correlation with the Dimensions of Obsessions and Compulsions Scale (DOCS), r (83) = 0.111, p = 0.319.

[ad_2]

Source link