Factors associated with low utilisation of cervical cancer screening among urban women in Lilongwe, Malawi: a cross sectional study | BMC Women’s Health

[ad_1]

Study design and population

This was a qualitative cross-sectional study conducted at Bwaila Hospital, a government hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi’s capital city, that serves both urban and rural people. The hospital, which is located in the heart of Lilongwe, offers both curative and preventive care, including cervical cancer screening. The facility was chosen for the study because it is the city’s sole government-owned hospital now offering cervical cancer screening services. Notably, Kamuzu Central Hospital, which serves as a local referral center, was left out because it does not offer cervical cancer screening. The district’s rural hospitals were not included in the current study, which focused on the urban setting. Similarly, while private urban institutions provide screening, the current research focused on low-income people whose primary access is through free government-mandated programs.

Sample recruitment strategy

There were two sample categories, and these were: (i) women and (ii) health workers. According to WHO guidelines, women between the ages of 25 and 50 can be screened using visual inspection with ascetic acid (VIA) [18]. Therefore, in the first category we recruited women aged 25 to 50 years old living in Lilongwe’s urban regions. The women were sampled using purposive sampling methods. These women were recruited at the health facility in a private area to provide privacy. The second category included health workers who had worked for at least three months at Bwaila Hospital’s outpatient reproductive family health unit.

Sample size

The health workers stated that they screen 17 to 20 women each day on average, which equates to 300 participants. In this study, however, saturation was attained at 24 participants. As a result, 24 women were interviewed. In the area of health professionals, there were two trained cervical cancer nurses and three additional health workers offering other reproductive health services, therefore, a total of five health workers were questioned.

Data collection methods

In February 2017, the lead investigator collected data at Bwaila hospital’s family healthy unit. Data were obtained through in-depth interviews with women in the Chichewa language following a topic guide, self-administered questionnaires in English for health workers, and participant observation in the health facility utilizing methodological triangulation. Prior to finalization, the tools were tested at the same hospital, with changes made to improve item clarity and sequencing. The interviews were taped with a recorder and later transcribed and translated by the lead investigator. Following the recording and verification of the transcripts, audio recordings and any missing notes were incorporated. Data on service delivery was gathered through participant observation (equipment, attitude, space, health education). The focus of the observation was on the time it took to open the clinic and close it, as well as the procedure of screening the woman as she came in for the service.

Data management and analysis

Data was verbatim transcribed and translated before being examined for content. The process of content analysis is systematically summarizing phrases or sentences while adhering to a classification scheme [19]. In this study, the lead investigator and an independent coder independently read the transcript several times to get the context. After familiarization with data, codes were developed, categorization and summary of verbal data was performed. After coding, the codes were classified into themes based on their commonalities. We used percentages to reach an agreement on the codes and reach on the final themes.

Trustworthiness in qualitative research

The following evaluative criteria were used to establish trustworthiness in the study: credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability [20]. Persistent observation, triangulation, prolonged interaction with participants, pushing for further information; and the use of women who came for services at the family health unit and had a direct personal interest in the topic was used to establish credibility in this study. The interview guide was used to preserve consistency in the questions, resulting in dependability. The proper and detailed description of the study environment, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria, assured transferability. The sample size was also mentioned, as well as the data gathering techniques. Confirmability was verified by audio recording and note-taking during interviews.

Data interpretation

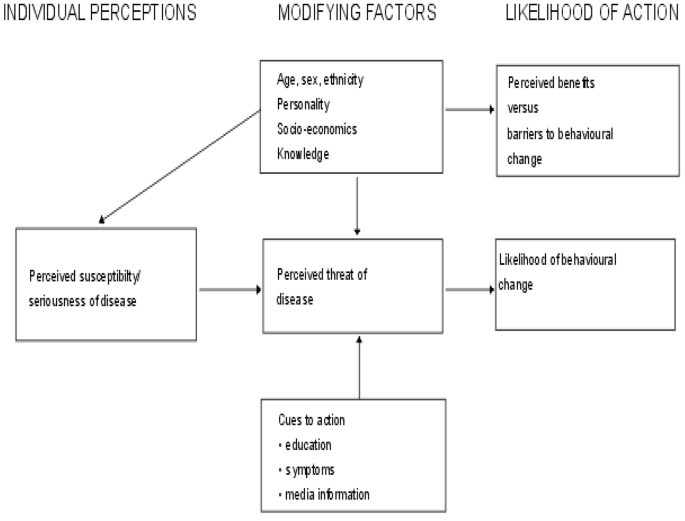

The research question was framed using the Health Belief Model (HBM) (see Fig. 1) [21]. This study focuses on individual attitudes and beliefs to explain and predict health behaviors [21]. The concept argues that an individual’s perception of susceptibility and severity of a health problem determines a threat, which increases the likelihood of taking preventative action in a health intervention that reduces the threat [21]. The model goes on to illustrate how modifying elements such as demographic, socio-psychological, and structural variables influence an individual’s perception of susceptibility, seriousness, advantages, and barriers to taking action on a health condition [21]. This is a preventive hypothesis, and it corresponds to the notion of cervical cancer screening as a preventive measure. Individual attitudes and beliefs are used to operationalize this [21]. Perceived advantages, perceived susceptibility, perceived restrictions, and perceived severity are the dimensions that the model focuses on [21]. People’s readiness to act is accounted for by these principles, which leads to the ability to exhibit self-efficacy [21]. According to the HBM, if a person believes that a negative health condition such as cervical cancer may be averted, he or she will take associated action (e.g., cervical cancer screening). Furthermore, the individual has a positive expectation that by taking a recommended health action, she will avoid a negative health condition, e.g., cervical cancer screening will be effective at preventing cervical cancer and believes that she can successfully take a recommended health action. That is if she can go for cervical cancer screening comfortably and confidently.

The Health Belief Model [21]

Application of the model to the study

The HBM shows how the following factors can influence behavioral change in terms of health prevention:

-

(i)

If a woman believes she is not at risk for cervical cancer, the chances of her taking preventive steps are minimal. It becomes difficult to voluntarily undergo cervical cancer screening.

-

(ii)

The severity of cervical cancer (perceived severity); if a woman is unaware that cervical cancer is a dangerous disease that cannot be treated at any stage, she may refuse to have her cervical cancer screened. If she believes it is a serious condition, on the other hand, she will seek preventive services.

-

(iii)

Women’s perceptions of impediments to cervical cancer screening services (perceived barriers); the challenges women have in obtaining cervical cancer screening services may influence their desire to undergo screening. Individual, cultural, religious, or service delivery variables may be involved.

-

(iv)

Perceived benefits vs. behavioral change hurdle; It will be difficult for a woman to go for screening if she is unaware of the benefits of doing so. This could be due to a lack of understanding of the advantages of screening.

Age, sex, ethnicity, knowledge, status, and personality are all modifying factors. Some women may refuse to have their breasts screened because they believe they are too young or too old. Some people may feel uneasy about getting screened by a male health care practitioner. Some people may be unable to attend a socioeconomic screening because they lack transportation and understanding about cervical cancer.

(vi) Inducing factors (cues to action), such as education, symptoms, and media information. Some women may seek screening if they are experiencing symptoms of cervical cancer. Others may come because they were directed to do so by medical staff, and still others because they heard about it on the radio or at a health talk.

[ad_2]

Source link