Getting the balance right – PharmaLive

[ad_1]

Getting the balance right

Even as their clients are trying to make clinical trials more diverse and equitable, agencies are continuing their DE&I efforts to build a culture where diverse talent is welcomed.

By Christiane Truelove • [email protected]

If there is a “positive” side to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is how the crisis illuminated the deep differences in the quality of healthcare in communities of color in the United States. From access to medicines to how pharmaceutical companies recruit for their clinical trials, pharma knows it has some work to do.

The development of COVID-19 vaccines highlighted not only the importance of clinical trials but the need to diversify them. However, there remains a barrier. Because of barbarities such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment – the most well known, but certainly not the only incident of abuse posing as medical science – there remains a deep distrust by PoC about participating in clinical trials. And these feelings of distrust are deepened by socioeconomic and healthcare inequities.

Driving efforts to diversify the population of clinical trials – at least when it comes to those in the United States – is the Food and Drug Administration. In April 2020, FDA issued a new draft guidance to the life sciences industry for developing plans to enroll more participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic populations into clinical trials. The guidance, titled “Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Subgroups in Clinical Trials,” recommends that sponsors of medical products develop and submit a Race and Ethnicity Diversity Plan to the agency early in clinical development, based on a framework outlined in the guidance.

“The U.S. population has become increasingly diverse, and ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health,” stated FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, M.D. “Going forward, achieving greater diversity will be a key focus throughout the FDA to facilitate the development of better treatments and better ways to fight diseases that often disproportionately impact diverse communities. This guidance also further demonstrates how we support the Administration’s Cancer Moonshot goal of addressing inequities in cancer care, helping to ensure that every community in America has access to cutting-edge cancer diagnostics, therapeutics and clinical trials.”

“The U.S. population has become increasingly diverse, and ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health,” stated FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, M.D. “Going forward, achieving greater diversity will be a key focus throughout the FDA to facilitate the development of better treatments and better ways to fight diseases that often disproportionately impact diverse communities. This guidance also further demonstrates how we support the Administration’s Cancer Moonshot goal of addressing inequities in cancer care, helping to ensure that every community in America has access to cutting-edge cancer diagnostics, therapeutics and clinical trials.”

Among the barriers identified by FDA about minority participation in clinical trials are mistrust of the clinical research system due to historical abuses; aspects of the trial design such as inadequate recruitment and retention efforts, frequency of study visits; time and resource constraints for participants; and transportation and participation conflicting with caregiver or family responsibilities.

Additional barriers could be language and cultural differences, health literacy, religion, limited access within the healthcare system, and a lack of awareness and knowledge about what a clinical trial is and what it means to participate.

“The FDA remains committed to increasing enrollment of diverse populations in medical product and drug development and will continue to engage with federal partners, medical product manufacturers, healthcare professionals and health advocates to reach this important goal,” officials stated.

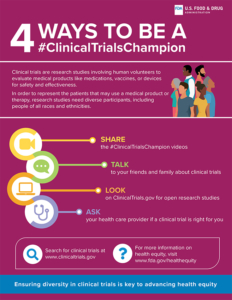

In addition to the guidance, FDA’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity created the “Diversity in Clinical Trials Initiative,” which includes an ongoing public education and outreach campaign to help address some of the barriers preventing diverse groups from participating in clinical trials. The office’s dedicated webpage has public service announcements and videos, social media outreach, and other resources such as infographics (“4 Ways to Be a Clinical Trials Champion”), a brochure (“Research Needs You”), and a fact sheet.

Industry actions for DE&I in R&D

While FDA has made some deliberate moves to encourage diversity in clinical trials, industry has been thinking about the problem for some time. TransCelerate BioPharma Inc. is a coalition of 20 pharmaceutical companies with “a vision consisting of healthcare providers (HCPs) that are activated and supporting patients along their healthcare and clinical research journey, where HCPs, sites and investigative staff are fully supported by trial sponsors, researchers have access to the data they need to improve study design, and medications are developed faster for patients in need.”

TransCelerate’s member companies are AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Shionogi, and UCB.

According to TransCelerate, there are R&D inefficiencies around approaches and processes for drug development. These have caused roadblocks for successfully starting, recruiting, executing, and completing clinical research studies, ultimately delaying the development of needed medications for patients.

There is a very practical reason for manufacturers to promote diversity in clinical trials, TransCelerate executives say. Not only does a lack of diversity lead to persistent gaps between trial representation and real-world disease burden, underrepresentation can limit confidence in future approved therapies and could lead to unforeseen consequences among impacted patient populations.

In 2014, TransCelerate launched its Diversity of Participants in Clinical Trials initiative, which executives believe will help accelerate improvements by equipping trial sponsors and other stakeholders with the tools and resources they need.

On its website, TransCelerate’s tools to promote diversity in clinical trials include “Diversity Community-Based Site Engagement and Capacity Building,”which identifies areas that clinical trial sponsors can make improvements; “Sponsor Toolkit Site Engagement and Capacity Building Considerations for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion of Participants in Clinical Trials (DEICT)”; and a reference table of available resources. These include BIOEquality, the Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP), and the National Minority Quality Forum (NMQF).

Jeneen Donadeo, executive director, portfolo solutions at TransCelerate, says the distrust pharma continues to experience about clinical trial participation is a “human” challenge, but one companies must be willing to take on. And as far as raising awareness of clinical trials, “I think the pandemic has helped us with that in a very odd way. Prior to COVID, how many people really gave much thought about research and development of medicines? If they took an aspirin or ibuprofen, were they thinking about, ‘Oh, I wonder how this was made? And who volunteered to make it and who was involved?’”

Post-COVID drug development is still probably a mystery to some people, but Donadeo says, “There’s more awareness now that [drug development is] there; it is something that needs to happen. And it does need participants – it’s not magically happening somewhere in a vacuum without the participation of humans in the process.”

Right now, one of the biggest challenges is access – how the industry can help to get the right participants into the right trials, Donadeo says. “One of the problems we’re seeing in so many diseases, is access to health care, access to the best health care, whether that is clinical trials or not – but clinical trials being part of that conversation,” she says.

For any patient, no matter what their background, the person that can help them make a decision to go into a clinical trial is their trusted healthcare provider. But when TransCelerate polled HCPs a few years ago about getting their patients into clinical trials, the organization found “in some cases, it’s not even on the radar [for HCPs] to recommend clinical research,” Donadeo says.

TransCelerate believes that more work needs to be done with HCPs to raise awareness of clinical trials, especially in communities of color.

“I think there is a ton of work to do in that whole trust piece, around how you get patients access to the trials, and how you get them relating to someone that you trust to help them make the decisions, and that has the right information to help them make that decision,” Donadeo says.

Based on these findings, TransCelerate has been focusing over the past year on efforts to equip clinical trial sponsors with better information about how to overcome the challenges of working with some sites.

Donadeo says there is no easy solution to the challenges of diversifying clinical trials, but in the end it has to be all stakeholders working together. “It’s not just pharma alone,” she says.

In October, Genentech released a video called “Question Reality,” part of its “Ask Bigger Questions” campaign on racial equity in health care. The video depicts the story of a Black woman throughout her journey with the healthcare system, first as a patient and later as an empowered Genentech scientist and leader. As a young girl, she questions why a doctor didn’t believe her, and as an industry-leader, she stresses the importance of asking bigger questions and addressing the root causes of systemic inequities in health care. The film was directed by Courtney Sofiah Yates, a Brooklyn-based and award-winning Black filmmaker and photographer.

“It is time that as an industry, we back up our words with intentional actions that tackle the root causes of systemic healthcare inequities,” states Veronica Sandoval, principal, inclusion and health equity, Genentech. “This crisis is not new. Barriers to access and quality health care have had generational impacts and have taken the lives of far too many people. Through this new campaign, ‘Question Reality,’ Genentech aims to elevate important questions that often go unheard and ignite a sense of urgency to address them.”

Sandoval told Med Ad News that while the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health inequity and widened the gap for underrepresented communities, “the problems we are seeing run deeper than just those brought on by COVID-19.

“At Genentech, we are actively working to dismantle systemic racism, which is a root cause of many health disparities and has contributed to poorer health outcomes for people of color and other marginalized communities. Our commitment includes tackling specific problems brought on by COVID-19, but is not limited to those issues.”

According to Sandoval, the “Ask Bigger Questions” campaign is not Genentech’s first and only initiative to advance health equity.

“We have also launched marketing and education initiatives to address the complex health inequities for Black and Hispanic/Latinx people with MS, who make up a combined 35 percent of the MS population, but account for only 13 percent of the population being treated today,” she says. “For example, we have developed and launched culturally relevant, multi-channel education, access solutions and support including Spanish direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising and an #MSVisibility campaign centering [on] the experiences of Hispanic/Latinx MS patients.”

While Genentech is trying to encourage an industry-wide movement for health equity, the company continues to focus on its own efforts.

“As the pioneers of the biotech industry, we have an opportunity and responsibility to use our resources to build deep and sustainable partnerships with stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem to make health equity a reality for all patients,” Sandoval told Med Ad News. “Genentech is uniquely resourced and positioned to have systemic impact within our company and beyond.

“Health equity is core to Genentech’s mission and strategy, and we seek to integrate a focus on equity in everything we do – from the design of clinical studies, to our access and policy priorities, to our investments in the community. We are committed to a health equity strategy that puts historically excluded patients at the center of what we do, and to fostering a healthcare ecosystem that earns the trust of and is accountable to all communities.”

According to Sandoval, Genentech has redesigned new clinical trials to accommodate more diverse populations. More than five years ago, the company implemented Advancing Inclusive Research, a cross-

functional effort aimed at addressing barriers and reducing disparities in clinical research participation for underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. Since then Genentech has launched the Advancing Inclusive Research Site Alliance and founded and partnered with its External Council for Inclusive Research to establish new standards and principles for inclusive research.

Since 2017, Genentech has invested more than $125 million in giving towards health equity and diversity in STEM-focused giving and national partnerships. And the company has conducted several clinical trials prioritizing the recruitment of historically underrepresented and excluded patient populations with a focus on diseases that disproportionately impact these communities.

“Together, we are sharing our key learnings with the industry at-large,” Sandoval says. “We recently published a peer-reviewed manuscript that included system, study, and patient level recommendations to improve the diversity of patient enrollment in clinical research.”

Trials that Genentech has redesigned to become more diversified include EMPACTA, CHIMES, and ELEVATUM.

EMPACTA (Evaluating Minority Patients with Actemra) study is a Phase III trial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. The study was designed in collaboration with physicians at hospitals with diverse patient populations, creating a streamlined process to identify and perform outreach. “Data shows that Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients have been disproportionately impacted by hospitalizations and mortality from COVID-19,” Sandoval states. “By meeting patients in their own communities, we were able to enroll 389 participants in under one month – 84 percent of whom were from underrepresented groups.”

CHIMES focuses on Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. The goal of the study is to optimize the protocol and simplify logistics to make participation as convenient as possible.

“As a result, the team put into place several interventions to remove barriers to participation, including on-demand transportation services, a patient stipend program, and culturally competent patient education materials,” Sandoval says. “These efforts helped the CHIMES team exceed its target, enrolling nearly 170 patients – 100 percent of whom are Black or Hispanic/Latinx – more than two months ahead of schedule.”

ELEVATUM is a post-approval study in USMA to understand the safety and efficacy of Faricimab in Black and Hispanic/Latinx diabetic macular edema patients.

“From the study’s inception, the ELEVATUM team used guidance from both CHIMES and EMPACTA to focus on design elements that will remove barriers to participation among underrepresented patient groups,” Sandoval says.

These elements will include door-to-door transportation service free of cost to the low- vision patients participating participants in the study, as well as stipends to compensate participants for the three-to four-hour imaging assessments that are required during visits.

“All therapeutic areas can benefit from more diverse clinical trial populations, but focusing on diseases that disproportionately impact underrepresented communities will drive forward a more equitable health system,” Sandoval told Med Ad News.

Beyond clinical trial access, Genentech is committed to ensuring that its medicines get to the people who need them, even if they can’t afford them. According to Sandoval, over the past 30 years, Genentech has helped more than three million people get the medicine they need through patient assistance programs such as Genentech Access Solutions and the Genentech Patient Foundation.

Genentech Access Solutions helps patients and their providers understand their healthcare benefits and insurance coverage and can help direct them to appropriate assistance programs based on their situation and need. “In 2021, we helped more than 255,000 people access the Genentech medicines they needed,” Sandoval says.

The Genentech Patient Foundation provides free Genentech medicine for eligible patients who do not have insurance or who have insurance but have been denied coverage or where their out-of-pocket costs are still unaffordable. Sandoval states that last year, Genentech provided free medicine to more than 60,000 people.

Expanding on the Genentech Patient Foundation’s mission to advance health equity, the company has initiated the CA & OR Latinx Farmworker Outreach Project, which aims to gain a deeper understanding of the access barriers that Latino farmworker communities in California and Oregon face, and connect with regional organizations in order to support access to free medicine.

In California, 92 percent of farmworkers are Latino, and most farmworkers – 53 percent – have no health insurance and limited access to healthcare, making them particularly vulnerable to environmental and occupational health hazards.

“In 2020 we launched our first Health Equity Study to elevate the perspectives and experiences of historically marginalized patient populations,” Sandoval says. “In 2021, we probed deeper and found that both patients and healthcare providers agree that the healthcare system needs urgent reform. By publishing the data from these stories and elevating the experiences of medically disenfranchised patients, we hope to spark action to address inequities across the healthcare ecosystem.

“We launched and published the study to amplify the voices of patients often forgotten, or talked about but not talked with/asked to engage in the conversation. Since then we continue to dedicate our resources and invest in initiatives that center the experience and voices of marginalized patients.”

Pfizer, Med Ad News’ 2022 Company of the Year, has taken a visible stance on clinical trial diversity. The company published a study in the July 2021 issue of Contemporary Clinical Trials, “Demographic diversity of participants in Pfizer sponsored clinical trials in the United States.”

The purpose of the study was to summarize the race, ethnicity, gender, and age data for Pfizer’s trials in the United States between 2011 and 2020. The results were used to establish a baseline of clinical trial diversity to measure improvement over time.

Pfizer analyzed the data set, comprising 213 trials with 103,103 U.S. participants, and found that overall trial participation of Black or African American individuals was at the U.S. census level (14.3 percent vs. 13.4 percent). Participation of Hispanic or Latino individuals was below U.S. census levels (15.9 percent vs. 18.5 percent), and female participation was at U.S. census levels (51.1 percent vs. 50.8 percent).

The analysis also examined what percentage of trials achieved racial and ethnic distribution levels at or above census levels. Participant levels above census were achieved in 56.1 percent of Pfizer trials for Black or African American participants, 51.4 percent of trials for White participants, 16 percent of trials for Asian participants, 14.2 percent of trials for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander participants, 8.5 percent of trials for American Indian and Alaska Native participants, and 52.3 percent of trials for Hispanic or Latino participants.

In its blog posting about the results of this study – “Doing Better: Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials” – Pfizer admitted that White people are over-represented in therapeutic trials, or those in which the treatment under investigation is likely to benefit trial participants in some way. 78.6 percent of therapeutic trial participants were White; 17 percent were Black and just 2.2 percent were Asian.

While more than half of Pfizer trials included Black participants at rates about equal to their representation in the overall population, Black people were under-

represented in cancer-related studies. Only about 16 percent of oncology studies included proportional representation of Black people, Pfizer executives say.

And Hispanic or Latino individuals are particularly underrepresented in cancer-related studies, with just 6.5 percent of oncology trials including proportional representation of Hispanic or Latino people.

Pfizer also found that Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Indigenous populations were under-represented, with some trials failing to include any individuals from these demographic groups.

“Volunteering to participate in a clinical trial – the foundation of medical research – is a selfless and personal choice that is often a challenge for many communities due to societal and economic factors,” stated Dara Richardson-Heron, M.D., Pfizer’s former chief patient officer. “Pfizer’s goal is to partner with patients’ and patient advocates to co-create solutions designed to lower many of the known barriers to clinical trial research such as financial challenges, lack of accessibility, the digital divide and many others. Pfizer must also do its part to increase awareness about the value and benefits of research and nurture relationships that will rebuild trust in our nation’s healthcare system.”

Pfizer says it has taken decisive steps toward eliminating healthcare equity barriers, including a company-wide commitment to diversity and knowledge

-sharing. “For clinical trials themselves, in some cases, researchers may cover participants’ travel expenses and utilize available digital technology to minimize (or eliminate) onerous on-site visits,” executives say, adding that Pfizer will also emphasize partnering with local clinics and grassroots organizations, and listening to the needs and concerns of individuals in the community.

“Overcoming barriers and challenges to fair representation won’t happen overnight, nor can it be achieved by a single company,” MacKenzie stated. “But it is the right thing to do for science, for public health, and for patients who are waiting for the next breakthrough.”

The continuing agency efforts of DE&I

Healthcare advertising agencies continue to focus on their DE&I efforts, but their work, and the work of their clients, has really just begun, executives say.

“We’ve all gotten past the easy part, which was simply having the conversations,” says Walter T Geer III, chief experience design officer at VMLY&R Health. “But now, the hard part is actually doing the work.”

Geer told Med Ad News that for smaller organizations, creating diversity is easy, but for other larger ones, it will be more difficult. “We [VMLY&R and VMLY&R Health] have almost 14,000 employees; I think we’re doing an incredible job,” he says. “But it’s also something that I would assume many people understand that it’s not a job that can be done overnight.”

Part of the work that needs to be done in diversity “is simply about ensuring that you have the right voices and the right individuals, and right ethnicities and backgrounds, on the work both in front of the camera and behind the camera,” Geer says.

He says VMLY&R has a culture studio, the job of which is to be able to talk about different areas of culture, areas that some people might not be comfortable with. “That’s important; [it] shows that we’re dedicated to getting the work done correctly.”

One of the barriers to doing any DE&I work is fear. “While many want to do the work, there’s a bit of fear of, ‘Well, if I do this, is it going to be wrong? And then oh, my gosh, I don’t want to get canceled,’” Geer told Med Ad News. “Then there’s the thought of, ‘Well, let’s just not do it at all, because we don’t want to get ourselves in trouble.’”

With the prevalence of social media, “we’re presented with a very difficult moment in time, because of the power of one individual sitting in their bedroom anywhere, being able to make a comment that has a potential of going viral and making a brand look bad,” Geer says.

On the positive side, Geer notes that over the past three years, VMLY&R’s health partners have had more people of color on the other side of the screen.

Geer attributes this to the shift in perception about the importance of pharma companies in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “If you said to anyone three years ago, that a pharma company would be the most well known brand in the world, everyone would say, ‘Hell no.” Because the first thing you’d think of are brands like Nike.”

With Pfizer and other pharma companies coming into the limelight, “I think that pharma brands had to rethink how they go to market, rethink what their story is,” Geer says.

As the pandemic highlights the health inequities for people of color, pharma has realized “getting it right means truly saving lives, and getting some of that wrong means we’re letting a vast amount of society down, and people could die over this stuff,” Geer says. “So pharma companies need to get it right, and have to get it right, and understand that getting it right means involving everyone, right to the table.”

This means a pharma company can’t have a table of six men trying to create a product for women with menstrual cycle problems – just as agencies “can’t have six people sit in a room as we try to solve a problem for a particular type of disability that none of us have,” Geer says. “It’s ensuring that you have a multitude of voices in these rooms. And we’re most certainly starting to see more of that now on the pharma side.”

For agencies and their pharma clients, the biggest challenge remains creating a culture that welcomes diversity, according to Geer. One of the difficulties in doing that is culture tends to conform to the norms of the majority. “People want to go to a place where they feel comfortable, and that means you’re going to a place where you have people that are similar to you – similar ways of thinking, similar way of walking, and talking and style, and all of that.”

This means it’s simply not enough to make diverse hires. “I’m kind of happy that we’ve gotten past the moment of, let’s talk about our DE&I numbers, because DE&I numbers, to me, don’t really mean anything,” Geer told Med Ad News. “I think that when an organization is leading with their diversity numbers, that is essentially saying, ‘Okay, so I’m buying my way into fixing this problem.’”

The solution to the problem is creating culture, Geer stated. “When I walk into an office, I can tell you in less than five minutes if this company is diverse or not.”

So how can a company create a diverse culture? The first step is finding the right talent. “The [healthcare advertising] industry as a whole needs to do a better job of identifying talent and where they pull the talent from,” Geer says.

Many tech companies excel because they don’t emphasize a tech background with prospective talent, “they could care less that you work in an agency at a publisher or a brand. They just want to find the talent,” Geer says. “Agencies, for a long time, all of us have felt as though finding the right talent means finding someone else who’s worked in an agency, because they have to get an agency environment and how agencies work.”

Geer himself has only been in the agency space for three and a half years. “And I will tell you, it is a challenge,” he says. “I’m still learning on a daily basis how a lot of this functions and works. It is an uphill challenge.

“But bringing in someone like I am, [with] an entirely different background from someone that you would typically see in my type of role at an agency – VMLY&R Health understood that was being disruptive. Being able to bring different and unique or inventive solutions and ideas means we need to bring different types of people to the table to execute on that.

“We just can’t rotate the same talent, it means pulling externally and looking at different types of individuals to bring to the table.”

Tope Ajala, global head of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Ogilvy, says for agencies and other organizations, getting that diversity of people is a talent war, which is being driven by how people feel they belong in an organization.

“So I always tell my team, representation creates communities, and communities stick together,” Ajala says. “So if you see a mass exodus of a specific group of people from your organization, they don’t feel like they belong, and they aren’t being represented fully.

“We’re realizing that communities really are a thing. Representation creates community, and we need to see more representation across all of our industry, whether that’s health, whether that’s advertising as a whole, and just whether that’s even within our leadership, [or] your organizational structure, how are you representing the people you want to come in house? And if you’re not representing them, then you’re not going to get them.”

According to Ajala, too often HR people are looking for prospective employees who are a culture fit, but in reality, are just “mini versions” of themselves.

“What we should be looking for is a ‘culture add’,”she says. “Is this person actually very different from us? Can they deliver the work? And most times, nine or 10 times actually, yes, they can deliver the work, so the right candidate you want to hire, the challenging part comes with, we will have natural biases.”

In assembling her own teams, Ajala says she has tried to go outside of her own experiences, to find people who not just complement the overall corporate culture, but who can add to it. Someone who is Muslim or Latinx, for example, would bring perspectives she does not possess.

“The more we learn about the differences people have, the more we start creating a better culture where anyone can come and thrive, and where anyone feels like they belong,” Ajala says.

Michelle Edwards, VP of operations and human resources at Heartbeat, says in building the agency’s culture, executives “are relentlessly in pursuit” of creating a Heartbeat community that mirrors the demographics of New York City, where the agency is based.

“We have a ways to go to be able to get the same statistics, breakdown demographics wise, in New York, but those are our big goals, to be able to match those same demographics.”

Geer notes that for pharma companies dealing with trying to reach patients of color, another problem that frequently pops up is authenticity.

“Number one is understanding that authenticity is everything,” he says. “And authenticity means understanding who you are, and understanding when to interject yourself into conversation, and when involving yourself in that conversation, knowing that it’s not to be speaking at people, but how to speak with them.”

Joining a conversation late “looks like you’re just trying to jump on the bandwagon,” Geer says, adding that achieving this understanding is difficult for pharma brands to do.

Geer believes that pharma can use tech to help bridge gaps. Partnering with tech companies such as Google or Amazon or Apple, all of whom have devices that patients are using to communicate in real time, can help pharma tap into those connected conversations and experiences and make health care more accessible.

At present, though, “When we get involved in clinical trials, there’s a significant amount of people who still don’t trust because of years of mistreatment,” Geer says. “And again, getting there, being able to do that appropriately, it’s the messenger that matters. Who’s delivering that message? Is it a pastor or a trusted individual?

“And most certainly, when you see brands that are trying to, diversify their clinical trials, because they understand the importance, you see then people on the other side of things going, ‘Nah, I don’t want to, I don’t trust that.’”

Another factor to contend with is that the HCPs who should be acting as the trusted intermediaries between patients and pharma and clinical trials may be operating under erroneous race-based assumptions.

“There are still doctors being trained today with misinformation like Black people have thicker skin and not as many nerves, [and] they have a higher pain tolerance – it’s crazy,” Geer says.

Five years ago, Geer experienced one of those doctors when he had an accident during a cycling race. “I cut my whole knee open, and the doctor literally said, ‘Oh, you’re a big, tough guy, we don’t need to give you any anesthesia.’ And he literally started sewing my knee up without any anesthesia.”

Pharma companies need to start diversifying their KOLs early in the product development process. “It is about tapping into the communities, and diversifying your teams and ensuring you have people on a consultative level who are sitting side by side along the entire process,” Geer says.

Ajala is passionate about DE&I because of the complexity of her own reality. “I’m British, born of German and Nigerian parents, now living in the United States,” Ajala says. “But when I first moved to the U.S., I was seen as African American, that was the first thing everyone saw, until they heard me speak. So automatically, you’re judged based off of your skin complexion, and where you’re located, forgetting that people obviously come from different walks of life.”

Wherever Ajala has lived – London, Dubai, Singapore, Germany, the United States – “my skin color is still the first thing I’m judged on. And that becomes the most challenging thing that I have to live with. And that shouldn’t be the case.”

For Ajala, the attitudes toward her that she has seen in the world are replicated in the workplace. “We hear these conversations around, you know, diversity matters, inclusion matters. We’re doing a lot about it. But are we really?”

DE&I programs can help an organization become more successful, “because people want to be where they see themselves.

“If representation is lacking in your business, it is going to fail,” Ajala says, “And there’s tons of examples around multiculturalism and how we market to different groups. But by eliminating and ignoring certain groups, you lose a seat.”

After the awareness of racial inequities was raised by the murder of George Floyd, Ajala noted with interest the number of articles that came out educating about DE&I.

“We weren’t comfortable in 2020, which is what I loved, which forced businesses to look inward and think about how they could change their industry specifically,” Ajala says, with pharma companies asking themselves questions about whether study data and pilot groups were reflective of the people they actually were trying to target.

“The question is, in 2022, have we kept the momentum going?” Ajala says. “And I’m afraid the answer is ‘no’ for most organizations.”

Like Geer, Ajala has seen fear slowing DE&I efforts. “[DE&I] makes people feel incredibly uncomfortable,” she says. “And I think you had no choice in 2020. It was in your face 24/7, and we were stuck at home.”

For leaders currently, Ajala says, “now that the uncomfortability is not in your face every day,” the challenge is to keep that DE&I momentum going, “to ensure that it’s still being spoken about in corridors, in meetings, with clients, with patients, with friends, with family.”

Edwards says one of the many ways Heartbeat keeps DE&I conversations going is though education. For example, the agency has a historian come in on a regular basis to teach about less well known aspects of events such as the assassinations of Malcolm X and John F. Kennedy, or about the slave trade and the destruction of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street.”

“We felt like just knowing our history, it helps you realize where we are and how we got here,” Edwards says. “And it helps to understand what are the things that we need to do to move forward.”

And for Heartbeat, though Edwards is proud of the achievements of the agency’s employee groups such as the Dismantling Racism group, “what got us to where we are is the foundation that we’ve built on how our leaders make decisions, how our leaders interact with people, how we all treat each other, how we communicate with each other, how we celebrate one another, how we collaborate, and how we support each other,” Edwards says. “[That] was the key to get to where we are, and all those things I talk about kind of exist on top of, in addition to, and because of that strong foundation.”

Without that kind of leadership and communication as a foundation, other companies may falter in their DE&I progress, Edwards notes.

Having Black History Month celebrations and other sorts of activities “is really low-hanging fruit type things,” she says. “A lot of companies, they just go straight to those things. But you really have to start with the foundation. And that’s really a mindset shift.”

|

Chris Truelove is contributing editor of Med Ad News and PharmaLive.com. |

[ad_2]

Source link