How menthol cigarette ads target Black people, women and teens

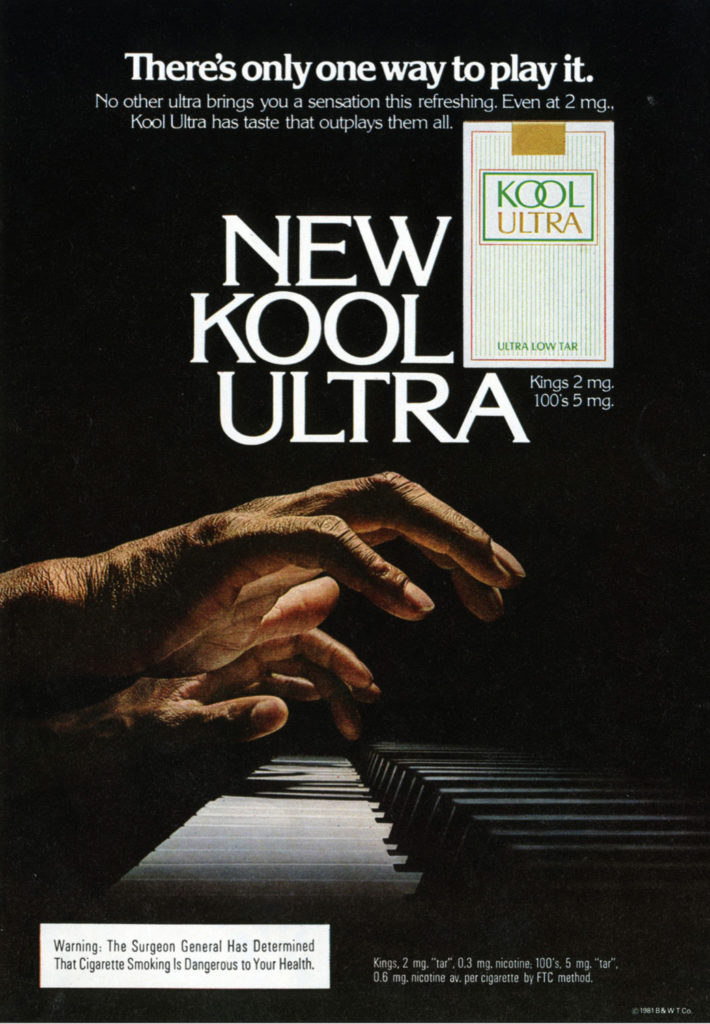

[ad_1]

In April, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced proposed rules to remove menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars from the U.S. market.

Though smoking rates in the United States are declining overall, the percentage of smokers who use menthol cigarettes is rising, according to Robert Jackler, MD, the Stanford School of Medicine’s Edward C. and Amy H. Sewall Professor in Otolaryngology. This growing popularity of menthol cigarettes is driven by advertising targeting teenagers, women and Black Americans.

To understand the role of advertising in the historical and present-day popularity of menthol-flavored cigarettes and cigars, Jackler and the Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising group developed a paper that compiles nearly a century of advertising campaigns for menthol-flavored tobacco products.

With the goal of providing the U.S. government and the public with evidence for initiatives to remove menthol tobacco products from the market, the research group documented tobacco industry advertising practices that have contributed to negative health outcomes for Americans.

The study shows that menthol cigarette advertising today mirrors messaging that has been used since the mid-20th century, emphasizing coolness and freshness. Today’s ads also use words and phrases like “organic,” “natural,” “additive-free” and “farm-to-pack” — erroneously implying that these products are environmentally friendly and have health benefits.

The paper also demonstrates how the tobacco industry has used intensive marketing to popularize menthol cigarettes, especially in Black communities, and to encourage use of menthol-flavored products among youth.

The American Heart Association funded the study, and its researchers assisted with preparation of the report, which was released Oct. 3.

I talked with Jackler, who has led the research group on the impact of tobacco advertising since it formed in 2007, about proposed rule changes and the role of tobacco industry advertising practices. Parts of the conversation are represented in the following Q&A, which has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What is menthol and why is it in tobacco products?

Menthol comes from the peppermint plant and is a mild anesthetic common in household items like toothpaste, cough drops and mouthwash. It is added to tobacco products like cigarettes because it imparts a minty flavor and reduces inflammation in the throat, making it easier to breathe more deeply into the lungs.

Many people think menthol cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes, a concept industry marketing has heavily promoted, but they are equally or more deadly.

Menthol tobacco products make up 39% of the overall cigarette market. Half of today’s adult smokers started with a menthol brand as teenagers, with menthol cigarettes being most popular among Black Americans: 85% of Black adults who smoke use menthols.

More than half of all young people between 12 and 20 years old who use combustible tobacco products start with menthol cigarettes, and 90% of Black teenagers who smoke use them.

This is why menthol-flavored cigarettes have been removed from the market in the European Union, United Kingdom and Canada. In the United States, they have been removed in some cities, counties and states, but not universally. The federal government is just catching up.

The goal of this paper is to provide evidence for the FDA as it defends its intention to remove menthol cigarettes and cigars from the U.S. market. Why focus on advertising?

The industry has historically targeted what it viewed as underdeveloped market segments for its menthol-flavored products. Looking back to the second half of the 20th century shows the ways the industry has orchestrated menthol to be the favored cigarette choice among teens new to smoking, women and Black Americans. These efforts paid off handsomely as they established durable brand preferences that still persist among these groups.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, the industry aimed menthol cigarettes toward health-conscious smokers, using claims that the additive could soothe your throat if you had a cold. By the 1950s and ’60s, menthol cigarettes were marketed as fashionable to women — advertisements suggested the taste was better and their breath would smell better.

Starting in the 1960s, the industry began branding menthol cigarettes for Black Americans, carpeting predominantly Black inner-city neighborhoods with menthol cigarette billboards while street vans distributed millions of free packs. Ads also appeared in Ebony and Jet magazines and in Black community newspapers.

Newport’s “Alive with Pleasure” advertising campaign, which ran from 1972 to 2016, was one of the industry’s longest running and most successful, establishing Newport as the leading menthol brand in America.

In it, vibrant-looking young models smoking Newports were depicted in playful group activities or romantic pairings. This formula made Newport a popular choice among new teen smokers.

Today, we not only have the traditional menthol brands (Newport, Salem, Kool) but we also have popular extensions of major non-menthol cigarette brands. For example, Marlboro offers 11 and Camel offers 12 menthol cigarette varieties, including Ice, Smooth, Rich, Bold, Gold, Silver and Black.

What can be done to mitigate targeted advertising from the tobacco industry? Is advertising from public health agencies an option?

The best way to protect vulnerable populations is to remove menthol tobacco products from the market, which the law allows the FDA to do for flavored tobacco products that are not in the best interest of the health of the American public.

Because of the asymmetry in resources between public health entities and the tobacco industry, public health ad campaigns can help only so much.

But it helps to ensure that the public and regulating agencies are fully informed about the tactics employed by the tobacco industry to attract customers, especially among their targeted populations.

In 1998, an accord — called the Master Settlement Agreement — reached between 52 state and territory attorneys general resulted in millions of internal tobacco industry documents being made publicly available.

This, and subsequent disclosures, have enabled us to document the industry’s promotional strategies in their own words. The material revealed major tobacco corporations’ targeting of Black communities, their efforts to recruit youthful smokers via menthol brands and their racially tinged attitudes toward what they referred to as “poverty markets.”

Targeted advertising is still driving the popularity of menthol tobacco products among these groups, including claims that menthol additives are healthy, organic and even socially cool, with the latter ads directed toward teens. The popularity of menthol is further boosted by emerging technologies such as crushable menthol capsules that deliver a burst of minty flavor.

What are your hopes for reducing the use of flavored tobacco products, even beyond menthol cigarettes and cigars?

The best way to reduce smoking in the adult population is to keep teens from getting started in the first place, because once someone gets hooked on nicotine’s addictive properties, it’s difficult to quit, even for people who want to.

The tobacco industry sees the writing on the wall with the overall decline in smoking and has been diversifying ways of delivering nicotine by branching out into minicigars, heated tobacco, a form of smokeless tobacco called snus and e-cigarettes — which are sold in a wide variety of youth-appealing sweet, fruity, menthol and minty flavors.

Removing menthol cigarettes and cigars from the U.S. market, as the FDA is attempting to do, is an important step toward reducing the harm caused by the leading cause of preventable disease and death in America.

Top image of a 1990 Newport “Alive with Pleasure” advertisement. All images are from the collection of Stanford University and the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising group. Read more at tobacco.stanford.edu.

[ad_2]

Source link