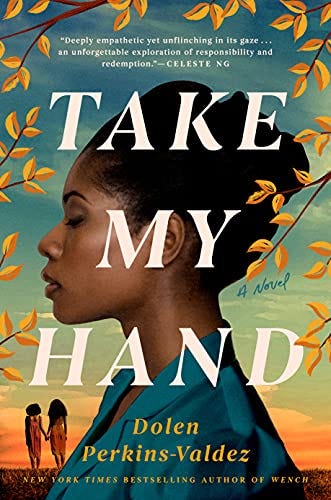

How the History of Forced Sterilization of Black Women Informed Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s Novel, ‘Take My Hand’

[ad_1]

Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s writing career may have begun in college when a short story that she submitted to a magazine was published, but she has loved books and storytelling since she was a child.

“I didn’t come from a reading household, so that’s how I knew I was a true reader,” she says. “[Books and storytelling] were a comfort to me.”

Perkins-Valdez believes that Black stories need to be told. Her debut novel, Wench, follows the story of four Black enslaved women before the Civil War, and her second novel, Balm, explores the lives of three people after slavery ended. Her third release, Take My Hand, continues her passion for highlighting Black stories.

The NAACP Image Award-winning novel highlights the stories of young Black women who were forcefully sterilized in 1973 by the federal government in Montgomery, Alabama. Although the novel was inspired heavily by the true story of Minnie Lee and Mary Alice Relf, two Black women who were involuntarily sterilized as young girls at a federally funded clinic, Perkins-Valdez says that it also was influenced “by every low-income family that found themselves being convinced that this was the right procedure for their children.”

Shondaland caught up with Perkins-Valdez to discuss Take My Hand, women’s health care rights, winning the NAACP award, and more.

KAYLA GRANT: What made you want to dive into this story?

DOLEN PERKINS-VALDEZ: I was just shocked it hadn’t been written yet. When I started researching, I was really astounded by how big a deal it was at the time. It was in every major newspaper. They were on the nightly news on every major network. They [the Relf family] had traveled to D.C. and testified before a Senate subcommittee, led by the late Senator Ted Kennedy. Yet I had gone through high school, college [as] an Afro American studies major, [and] had gotten a Ph.D. with a focus in African American literature in history, and I didn’t know this story.

This is a story that I believe was willfully and intentionally swept under the rug of history. The gap in the historical narrative regarding what happened to these women was so appalling to me. I said to myself, “I have to write this book. People must know this story.”

KG: As you said, Take My Hand explores a situation that was erased in history. Why is it important for the younger generation to learn about these moments in time?

DPV: Black women matter. Black women’s histories need to be told and retold. Many people know about the Tuskegee syphilis experiment because there was a movie made about it, and there was a presidential apology from [former] President Bill Clinton to the victims. There have been omissions in the historical record that particularly involve Black women, so my first thing is people need to be more inclusive about Black women’s history.

The second thing I will say is [that] everything has a context. When we think about, for example, Black distrust of the Covid vaccine or of medical professionals, there’s a history there. There’s a reason why we don’t want to be the first in a clinical trial. I think these histories matter in the contemporary moment not just because we’ll repeat the same thing, but there needs to be context to why we are who we are, and why we react the way we react. If we don’t have that context, our outrage appears to be paranoia, and it appears to be unfounded.

KG: There seems to be an attack on women’s health care rights, which makes the story more relevant in the modern day. What is the main message that you want readers to take away from the book?

DPV: I want people to just be talking about this. We are in an era where we have to be very careful. In the book, [the character Civil Townsend] learns the hard way that good intentions can still harm people. I think there’s some really well-intentioned people out there who are making mistakes about this issue.

We need to be strategizing in our communities. I hope that when people read this book, it just fosters conversation. That’s the first step, and if you have that conversation, you really can change. I believe in the power of words, literature, and books to change hearts and minds. If you change hearts and minds, then you can change the world.

KG: What can women do to advocate for themselves in health care?

DPV: It’s interesting because when you talk about those disparate health outcomes for Black women, it persists across socioeconomic status. I don’t have all the solutions, but I would say we need to be discussing it among ourselves.

I think it’s really important that medical schools read my book. If you’re in an ob-gyn residency program, you need to know this history. You should not be doctoring on Black women if you don’t know this history.

I talked to a lot of women about really taking time to search for a good doctor who listens. It’s not easy to find, but they’re out there. Then, the last thing is to inform ourselves. We have to be really highly informed. We have to talk to each other, support each other, and then we have to be very aggressive in finding good health care providers.

KG: With Mental Health Awareness Month coming up in May, how do you balance your mental wellness with the heaviness of this topic?

DPV: For me, I find knowing the history [and] writing about the history really empowering because it explains things to me. I think the people who see this history as really depressing are the people who see Black history as a history of victims. I will tell you that I see this as a history of survivors. The Relf sisters are still alive, and they are well. They have love in their lives. They’re not mourning this every day. They lived to tell the story, and they survived it, and their families survived it. I have the utmost respect for the Relf sisters.

When you see that famous photograph of that enslaved man [Gordon] with a welts on his back, and he’s sitting looking dignified, that is our history. It’s about dignity in the face of overwhelming oppression and choosing life. The way we can sort of manage knowing some of these really terrible things that happened is knowing that it didn’t kill us.

KG: You recently won an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Fiction for Take My Hand. How did it feel to win that and receive that recognition?

DPV: I call it my Black Oscar. That is just an amazing room to be in. I really honor all of the nominees this year because to just be in the room with those folks was so special. There was so much love. It was an honor of a lifetime. It’s fun and all to do the Pulitzer events and National Book Awards. I’m on the board of the PEN/Faulkner, [and] we give a very prestigious award. Those are fun rooms to be in too, but there is nothing like that NAACP Image Award room.

KG: What was your favorite part about writing this book?

DPV: When I was writing it, I really liked being in the ’70s because I’m a ’70s girl. I was born in the ’70s, but I wish I had been, like, an adult because I would have loved the fashion and the Afros and the music. That was the fun part about writing this book. The best part about it since it’s been published has been talking to women. I’ve been enjoying the sisterhood, and we’ve been sharing a lot of stories. I feel like the book has created these conversations in a sacred space where we can actually open up. The best gift a novel can give us is that it can open us up.

KG: What is your advice for aspiring authors?

DPV: If this is your passion, it will happen. I’ve never known anybody who really wanted this that it didn’t happen for. If your book doesn’t sell or get published, write another one. I wrote three novels that never sold before I sold my first book, so keep writing; read everybody and everything. I would [also] say know your readership, whoever they may be, honor them, and take care of them.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Kayla Grant is a multimedia journalist with bylines in theGrio, Oz Magazine, Prism, Rolling Out and more. She writes about culture, books and entertainment news. Follow her on Instagram: @TheKaylasGrant.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY

[ad_2]

Source link