Incarcerated and invisible: What happens to pregnant people in Georgia’s county jails?

[ad_1]

One Sunday evening shortly after Christmas 2019, Amy Ard received an email. “Wondering what resources are available to a young woman that’s pregnant (did not know until after her arrest),” it said. The message continued: This woman had no money, wasn’t in contact with her family, and was still in jail awaiting her hearing. Could Ard help?

One Sunday evening shortly after Christmas 2019, Amy Ard received an email. “Wondering what resources are available to a young woman that’s pregnant (did not know until after her arrest),” it said. The message continued: This woman had no money, wasn’t in contact with her family, and was still in jail awaiting her hearing. Could Ard help?

The woman in question was 27-year-old Aubrey Newsome. She had been driving drunk after her restaurant shift in Augusta when she hit an oncoming car, then fled the scene. The accident resulted in the death of Charnia Eccleston, an 11-year-old girl riding inside the other vehicle. Newsome, who had several prior arrests involving drugs and alcohol, was charged with vehicular homicide and driving under the influence. She was detained at Augusta’s Webster Detention Center and, because of the seriousness of her charges, wasn’t offered bond. A few weeks after her arrest, Newsome tested positive on a pregnancy test provided by the jail. She estimates she was only a few weeks pregnant when she was arrested.

The person who sent the message was a woman named Shelley, whose 22-year-old son was the likely father of Newsome’s baby. (Shelley asked us not to print her last name, in order to protect her family’s privacy.) Shelley, a self-employed house cleaner, “didn’t know this girl from Adam,” she told me. She’d barely met Newsome during her son’s brief fling with her, and she didn’t particularly like what she saw—she described Newsome, who waited tables at Hooters, as a “Girls Gone Wild type.”

At the same time, Shelley couldn’t imagine the anxiety and uncertainty that a pregnant woman—estranged from her family, detoxing cold turkey from alcohol, facing serious charges, and confronting the fact that she’d just taken a life—must feel in a jail cell. A mother of two, Shelley also couldn’t imagine losing her first grandchild to the foster system, which was likely if no one else stepped in; Newsome, who had a daughter from a previous relationship, had no contact with her family, and Shelley’s son wasn’t interested in starting a family with her. “I just had to try and put myself in her place,” she said.

Shelley started by asking one seemingly straightforward question: What happens to pregnant women in county jails? She had read of prisons in other states designed for pregnant women, some of which even had nurseries. But she was surprised to learn that there were no clear answers for women in jails. It was her own googling that led her to Ard, the executive director of Motherhood Beyond Bars, an Atlanta-based organization that provides support and education in Georgia to incarcerated and recently released mothers, their children, and their children’s caregivers.

Ard responded the next morning. There wasn’t much she could immediately do, she explained: Motherhood Beyond Bars works with women in prisons rather than jails. Once pregnant women are sentenced to state prison, she said, they’re sent to a facility with access to standard prenatal care. Jails, on the other hand, are designed to hold people temporarily as their cases progress through the legal system. She asked Shelley to provide more information, and assured her that she’d try to help.

The two remained in touch. As Newsome waited, Ard kept asking Shelley about Newsome’s medical care. “What Shelley was reporting back to me was just unbelievable,” Ard said. “There was no plan.” (Administrators at Webster Detention Center didn’t respond to an interview request for this story.)

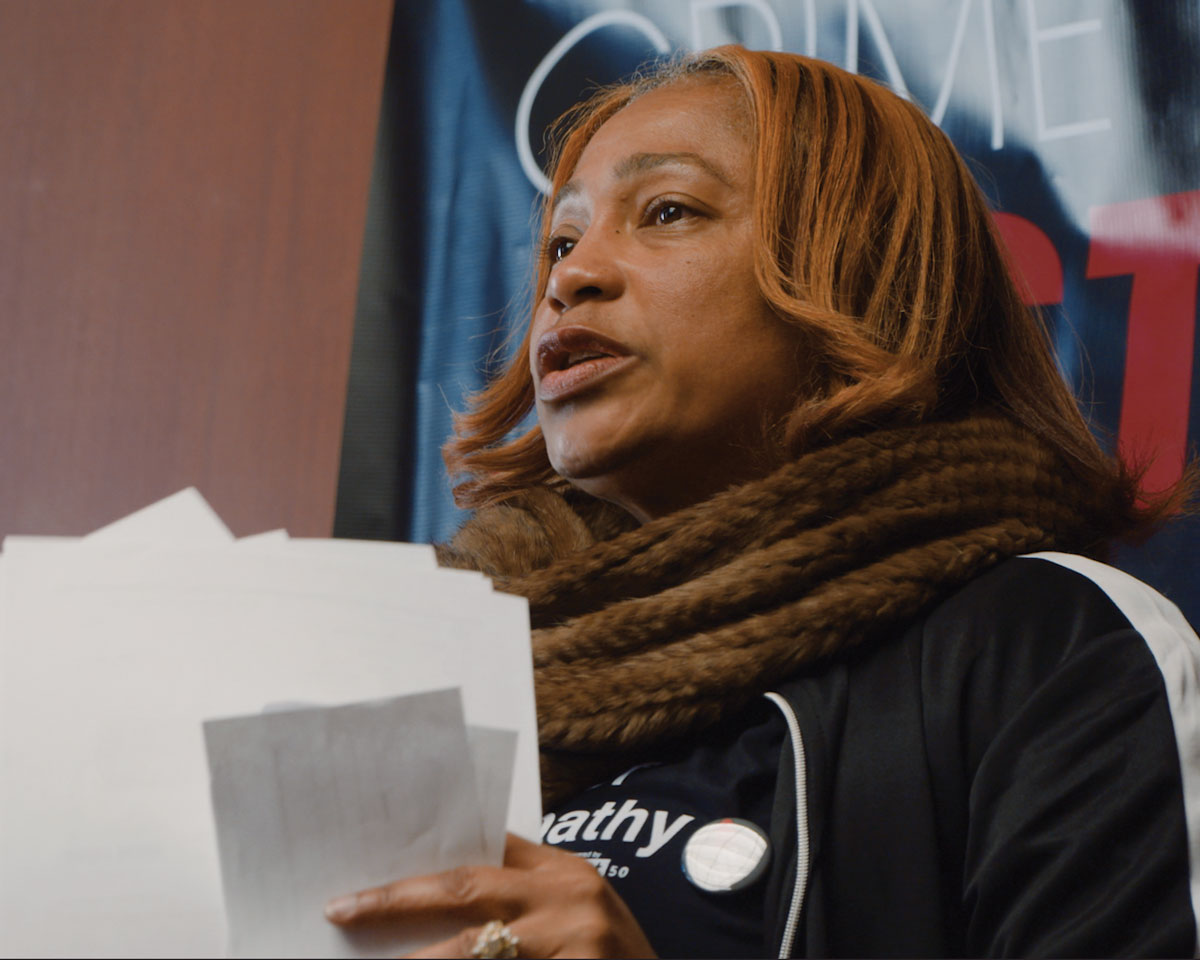

Photograph by

Johnathon Kelso

Over the next several months, and as the pandemic set in, that conversation sparked a bigger, more troubling question for Ard: How many others were in Newsome’s situation? Jails, while constitutionally required to provide healthcare to people in detention, are not equipped to care for pregnant people throughout their entire pregnancy. Meanwhile, Ard noticed an anomaly in state prison data: In 2021, the average number of women giving birth in the Georgia Department of Corrections system had plummeted. “We expect 50 to 70 births a year in Georgia’s state prisons, and we were seeing more like 20,” Ard says.

The pandemic had forced courts to shut down, and the backlog was piling up, forcing people who hadn’t been convicted of a crime to wait longer and longer in pretrial detention. Ard worried there were more women in Newsome’s situation: pregnant, unable to access routine medical care, afraid that the biological clock of pregnancy and labor would eventually outpace the pandemic-clogged court system. “I didn’t think the state had suddenly done a better job of serving vulnerable women,” she said. “I thought they were probably all just sitting in jail.”

Ard worked as a doula in Washington, D.C., for a decade before getting involved with Motherhood Beyond Bars. It was during a client’s birth in a D.C. hospital that her career took a turn: Walking out into the hallway to fetch ice chips for her client, she saw a pair of handcuffs hanging off of a gurney, outside a hospital room where an armed guard was posted. “It was an image that stopped me in my tracks,” she said. She couldn’t ignore the contrast between her client’s birth and that of the woman just one room over—both women were in labor, but one was shackled to a bed, alone and without support. “I went back and finished my job that day, but nothing was quite the same after that,” Ard said.

Ard returned to Atlanta, her hometown, in 2017 and started working on changing the laws—at the time, it was still legal to shackle pregnant women in Georgia, and legislation addressing it had failed twice before. She met a woman named Bethany Kotlar, a student at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health who’d written a childbirth curriculum for incarcerated women in Georgia prisons. Kotlar, working to distribute the material to the state’s prisons, called the program Motherhood Beyond Bars. Kotlar was heading to Harvard for her PhD, so Ard offered to take the reins of the project, continuing what Kotlar had started with just a few volunteers, no budget, and no salary: educating incarcerated women about pregnancy and birth, hosting postpartum support groups in prisons, and working with other activists and lawmakers to get the handcuffs off of pregnant women.

Two years later, Georgia passed the Dignity Act, which placed restrictions on the use of shackles or solitary confinement on incarcerated pregnant women. The effort to pass the bill was led by a formerly incarcerated woman named Pamela Winn, who had been pregnant during her sentence but miscarried after falling while shackled; out of prison, Winn became an activist who’s worked with criminal justice–reform advocates in states around the country to pass antishackling legislation, among other projects. (See sidebar at the end of this story.) In Georgia, the antishackling bill that became law wasn’t quite the same as what Winn had written: Originally, it also included an amendment that would have required all of Georgia’s county jails to record the number of pregnant women in their custody and share that information with the Department of Public Health. But that amendment didn’t make it into the final bill.

As a result, no one knows how many pregnant women are locked up in Georgia’s jails at any given time. Organizations like Motherhood Beyond Bars can track and reach out to every pregnant woman who enters the state prison system, but that’s not the case for people confined in the state’s 183 county jails, each of which operates independently, with no state-level oversight. Had Shelley not approached Ard, Newsome’s situation would have remained as invisible as any of the other pregnant women sent to jail each year.

Advocates argue that this lack of transparency allows jail administrators to avoid public scrutiny, prevents organizations like Ard’s from providing resources and services to women and their families, and makes it impossible to work toward better health outcomes for incarcerated mothers and their children. “We know that these women are, in some sense, high-risk and vulnerable to poor health outcomes,” Ard said. “And we also know that the minute that baby is born, they’re born with the deck stacked against them. It would be great to connect them to services that can provide education and support. But we can’t do that if we don’t know who they are or where they are.”

While the total number of incarcerated people in the U.S. has skyrocketed since 1970, the number of women in prison has increased at a rate twice that of men. Statistically, women receive harsher sentences—even for low-level offenses—and often encounter barriers upon reentering society without safety nets. As for how many are in county jails, the data is scarce and outdated by nearly a decade but tells an equally bleak story: According to an analysis by the Vera Institute of Justice, the number of women in jails across the U.S. has surged from under 8,000 to nearly 110,000 over the last four decades, with people of color and low-income populations disproportionately represented. The majority of that population—nearly 80 percent—are mothers, largely single parents. The vast majority have been victims of rape, domestic violence, or child abuse. Approximately 5 percent are pregnant when they’re arrested. (While transgender men and nonbinary people can also become pregnant, very little data has been collected about their birthing experiences and medical care in the carceral system; pregnant cisgender women are the subjects of all the statistics we do have, and of various pieces of legislation pertaining to this issue.)

And many, while presumed innocent pending the outcome of their cases, are trapped in pretrial detention because they can’t afford bail—a phenomenon exacerbated by the pandemic, which has led to a massive backlog in the court system. (By February 2021, the AJC reported, 730 people in Fulton County Jail had been awaiting trial for at least a year.)

Dr. Carolyn Sufrin, an associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins, studies reproductive healthcare in the corrections system. She explains that, while courts have identified a constitutional right to healthcare for incarcerated people under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment,” actual care varies wildly from one jail to the next. “There are no mandatory standards of healthcare that prisons and jails have to abide by, and no mandatory systems of oversight that exist for prisons and jails, and so, what you get is complete variability,” she said. “You have some jails that provide a reasonable quality of pregnancy care, and others that provide abysmal, neglectful, dangerous care.”

Sufrin herself has worked with prisons and jails to collect data through the Pregnancy in Prison Statistics project. “If you don’t have a sense of the scope of the problem, then no one pays attention to it, and it perpetuates the neglect,” she says. “The way I’ve summarized it in some of my work is, women who don’t count don’t get counted, and women who don’t get counted don’t count.”

• • •

By early 2020, Ard had spent three years working to expand Motherhood Beyond Bars’ services and secure the organization’s nonprofit status. She also had interns. Together, the team made a list of every jail in the state and began making phone calls. Their goal was to offer pregnancy-education curriculum to each jail, offer to help establish standard operating procedures for pregnant people, and find out how many were being held. It took the team about two months to work their way down the list.

Ard estimates that about 10 percent of the jails were forthcoming with information. “They weren’t spilling the beans left and right,” she said. And none of them accepted the team’s offer to share prenatal resources. But the ones that did take the calls surprised her: The Clayton County jail reported nine pregnant people in detention. Walton County had six. Daughtry County confirmed that it had some, but wouldn’t reveal how many. Overall, Ard said, “there were a lot more pregnant women than we expected.” But without the cooperation of the jails, Ard still only had a glimpse of the problem’s breadth.

One of those women, of course, was Aubrey Newsome. As her pregnancy progressed, she and Shelley spoke nearly every day. Shelley wasn’t even certain that her son was the father of Newsome’s baby. (Later, a paternity test confirmed that he was.) Still, she felt compelled not just to act on behalf of her future grandchild but to remain a presence in Newsome’s life when few others had. She took on both responsibilities like a job.

After connecting with Ard’s organization, Shelley began regularly relaying details about Newsome’s care that surprised even Ard. Newsome alleges that she was seen by an obstetrician only about five or six times throughout her entire pregnancy. On a standard schedule of obstetric care, low-risk women are typically seen about 15 times, increasing in frequency as the pregnancy progresses. Newsome, who was dependent on alcohol and on a treatment regimen for opiate addiction at the time of her arrest, would be considered high-risk. She also says that, when she was around eight months pregnant, she was assaulted by another incarcerated person but wasn’t examined until a couple days after the fact, after Shelley had called the jail repeatedly. After being denied bond twice, Newsome began to accept the real possibility that she might give birth behind bars.

In the summer of 2020, as Newsome’s July due date approached, Ard started making calls. Word eventually reached Jodi Lott, who represents Georgia’s 122nd District in the state House. Lott called the jail, Ard said, “and the next thing we know is, the jail is asking the judge for this woman to be bonded out.” (Lott didn’t respond to a request for comment.) The hearing was successful for her: Judge James G. Blanchard Jr. agreed to a $20,000 special-conditions bond requiring house arrest at Shelley’s home and a SCRAM ankle monitor.

Shelley took a weekend to borrow enough money from a friend to pay a bondsman to post the full amount. The following Monday, she picked Newsome up from Webster—“looking like she was about to burst,” Shelley said—and took her to the probation office to have an alcohol monitor cuffed to her pregnancy-swollen ankles. On Wednesday, after scrambling to secure emergency Medicaid coverage for Newsome, they headed to the hospital for her first prenatal exam in three weeks. Eight days later, Newsome gave birth to a healthy, eight-pound baby boy. During labor, Ard offered doula support over the phone. Shelley cut the umbilical cord.

• • •

After the birth, Ard wrote a letter to Probation Services, asking for a little more time for Newsome to heal and breastfeed her baby before returning to jail. Newsome was allowed to stay home with her newborn until her sentencing hearing in court—10 weeks, a far more generous amount of time than any of them had realistically hoped for.

What would’ve happened if Newsome had gone to prison early in her pregnancy, rather than spending nearly her entire term in a county jail—then being released to give birth only through the efforts of two dedicated advocates? After being sentenced, she would have been transferred into the custody of the Georgia Department of Corrections and eventually transported to Helms Facility, a state prison equipped for incarcerated pregnant women. After giving birth, she wouldn’t have been able to sustain a breastfeeding relationship, or the prolonged skin-to-skin contact recommended by the World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics to strengthen the mother-infant bond. She wouldn’t have experienced the surreal first few weeks after bringing a newborn home—not the delirium of sleep deprivation nor the ecstasy of seeing a first smile. Instead, she would’ve had a day or two—or, as some women experience, only a few hours—with her newborn before handing him off to a nurse and being transported back to prison.

For Newsome, the 10 weeks she was able to spend at Shelley’s home were about bonding with her infant. For Ard and other activists, they were proof that this model could work for other women, too. The Georgia Women’s CARE Act would allow pregnant women to defer their prison sentences until six weeks after giving birth. The bill was introduced during the 2021 legislative session but didn’t go up for a vote; its sponsors plan to reintroduce it in the 2022 session.

Pamela Winn, who authored the bill, believes it will pass, saying she wrote it in a way that should appeal to lawmakers on both sides of the aisle: from Republicans opposed to abortion to progressives concerned about the state’s Black maternal-mortality crisis. (Georgia has one of the worst maternal-mortality rates in the nation, and Black women are nearly three times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than white women are.) “Georgia is a state that says it cares about its babies,” she told me, referencing the state’s 2019 antiabortion “heartbeat” bill. “You have to own up and walk the talk. If you say you care about babies, then you should care enough about all babies.”

The Georgia Women’s CARE Act will also resurrect the data-tracking amendment that was scrapped from the 2019 antishackling bill: If passed, jails would be required to submit annual data to the Department of Public Health, including the total number of pregnant women incarcerated in their facilities. Representative Kim Schofield, one of the bill’s sponsors, said the resulting data could be used for funding, addressing the maternal-mortality crisis, and improving jail conditions overall. “[Legislators] should be given access to the data that we need to make decisions based on the interests of the population, and for the whole system,” says Schofield. “This is a human-rights issue.”

In 2019, the amendment was scrapped because of pushback from Georgia’s sheriffs, who continue to oppose the provision. Terry Norris, the executive director of the Georgia Sheriff’s Association, which lobbies at the Georgia General Assembly on behalf of the state’s 159 elected sheriffs, said his constituents typically won’t support any state-imposed mandate, adding that most of Georgia’s jails are critically understaffed, and none of them receive funds from the state. “It might be a great practice, but they don’t want a mandate because there’s no money in some of these counties at all,” Norris said. “It’s something else they’ve got to keep up with.”

“They’re already counting,” Winn told me. “It’s not like it’s something that they don’t do throughout the day. We weren’t asking for them to create anything, or do anything that they don’t already do or should not already have.” (In 2015, Texas successfully passed a law requiring county sheriffs to collect and report prenatal care data to the state’s Commission on Jail Standards.)

Norris also told me he doesn’t see a point in tracking pregnant people in jail. “There’s no sheriff that wants to keep a pregnant lady in jail, simply because of the cost,” he acknowledged. “But it’s no different than any other inmates who come in with health matters.” I suggested that it seems everyone can at least agree that no one wants a baby born in a jail cell. Norris said, “When those [antishackling] bills were coming up a couple years ago, I couldn’t find a sitting sheriff that had even heard of an inmate delivering in a jail cell, ever.” While it is rare, though, it isn’t unprecedented: In 2012, DeShawn Balka sued the Clayton County jail after she prematurely delivered her baby in the toilet of her cell. She was only five and a half months pregnant, and her baby died shortly after she gave birth.

• • •

Newsome’s son is a toddler now, with the same soft, pale ringlets his father had as a baby. Shelley, now 50, is his primary caregiver. On a warm October afternoon, the three of us sat at a playground next to the local library. Shelley is friendly and warm, an easy conversationalist with a lilting Georgia accent and a candor that doesn’t sugarcoat anything about how strange and stressful the last two years have been. As the toddler led us on an improvised obstacle course around the playground equipment, playing peek-a-boo through the jungle-gym bars, we commiserated about daycare germs and sleep schedules. My son was born just a few days before Newsome’s was.

While the boy’s father helps with parenting duties, Shelley is the one taking him to pediatrician appointments, juggling childcare with her work cleaning houses, and keeping up with the physically and mentally exhausting role of caring for a toddler who simply wants to explore, climb, and taste everything. “It’s like having a little billy goat in the house,” she said.

Shelley’s phone rang; the caller ID said Securus Technologies. Shelley looked over at the child. “Who’s that?” she said to him in a singsong voice. “It’s your mama calling.”

Every day, Newsome calls Shelley from Emanuel Women’s Facility in Swainsboro, where she’s serving a 10-year sentence, so that her son can hear her voice, and she can hear his. With visitation limits still in place because of the pandemic, she hasn’t seen him since he was 10 weeks old, despite being vaccinated. Shelley pays for credits on Newsome’s account to cover the cost of phone calls, which are 15 cents a minute, and to regularly send her pictures and videograms through the prison’s communication portal: short videos of him learning to crawl, taking his first few wobbly steps, playing in the rain.

In the phone calls I had with Newsome, she told me about her life before the accident. She was dependent on alcohol, but making progress in her treatment for opioid addiction. The week before the crash, she’d gotten her class schedule for Augusta Technical College, where she planned to study sonography the following spring. She remembers the discomfort of her third trimester, when the baby would kick relentlessly whenever she tried to lie down on her cot, and when the whole building reeked of industrial-strength bleach as the jail staff disinfected surfaces. Toward the end of the pregnancy, she saw a Pampers commercial on TV, watching a woman holding her newborn to her bare chest. “I just lost it,” she says. “I didn’t know what was going to happen.” The one constant was Shelley, who answered Newsome’s phone calls every day. “Shelley’s been in my life more than my family has,” Newsome said.

Shelley acknowledges it’s an unusual arrangement: two women, two decades apart in age, both from different walks of life, who’d never met before, figuring out how to participate in child-rearing together. They aren’t sure what will happen in the future, when Newsome is released: Where will she live? Will the two women share parenting duties? By the time Newsome is free, her son will be a fifth grader on the cusp of puberty, eager for independence. Even if Newsome is offered probation before the end of her sentence, Shelley will have been functionally filling the role of motherhood for Newsome’s son from the time he was 10 weeks old.

People often ask Shelley why she chose to get involved with Newsome, and why she continues to have a relationship with her. “She has nobody else,” Shelley said. “And I want to do what I feel is right, so that she knows that the way she grew up—she needs to break the cycle and do things different.” Shelley doesn’t paint her efforts as heroic, and she doesn’t gloss over the horrific event that landed Newsome in jail to begin with. Still, she was particularly disturbed by the local online reactions to the news of Newsome’s temporary release, suggesting that Newsome didn’t deserve medical care, or that it didn’t matter what happened to her baby. “It just made me sick,” she said.

It’s a sentiment that Ard and criminal justice–reform advocates face regularly: that the people who commit crimes like Newsome’s are simply reaping what they’ve sown. Why should someone like her get special treatment, or even basic dignity, after taking a life—after taking a mother’s child? The answer, for Ard, isn’t just that incarcerated people have a constitutional right to healthcare, or even that every human being has a story extending beyond their worst decisions. It’s a chance to disrupt the cycle that brought them into prison to begin with.

“It’s cliche, but birth is this transformational moment,” Ard said. “We have these people who we’ve decided are ripe for a transformation, and we waste that by shackling them to a bed and removing their baby.” Could that experience not be an impetus for real transformation in that woman’s life, which could ripple outward to her child, and to her family, and even to her community?

Ard has heard story after story from the women she works with: victims of abuse and trauma, born into poverty and neglect, growing up separated from an incarcerated parent—or, as in Newsome’s case, growing up surrounded by substance abuse and addiction. Many did the best they could; some made enough mistakes along the way to end up in prison. “I’d like to be able to rewind that clock for them, but I can’t do that,” Ard said. “So, I guess I’m trying to rewind the clock for the next generation—to make that generation be the last one that sees prison walls.”

Photograph by Joseph East, Brave Voices Media

After miscarrying in a Georgia detention center, Pamela Winn became a powerful voice for women in prison—and for those trying to leave it behind.

By Ariel Felton

In 2017, Pamela Winn was at a drug policy–reform conference in Atlanta, preparing to help lead a discussion about the war on drugs. A budding activist for criminal-justice reform, Winn had put together a speech about her mother’s experience with substance abuse and how it affected her. Still, among the lawyers and academics, she felt uncomfortable. “I remember saying, Why do they have me on this panel?” said Winn, a mother of two and former registered nurse. “I’m not an attorney. I don’t do research.”

Then, she heard a statistic that caught her attention: Private prisons, a panelist noted, make billions of dollars each year managing the detention of incarcerated people in the United States. (In 2015, two years before Winn’s conference, the two largest private-prison companies in the country reported combined revenues around $3.5 billion.) The sentencing boom created by the war on drugs fueled the growth of for-profit detention facilities, which have been plagued by reports of neglect and abuse. Winn, though, had firsthand knowledge of the problem: Less than a decade earlier, she miscarried while in custody in a privately run facility in Georgia. “All I could think of is, these people make that kind of money, and they couldn’t do anything for me,” Winn recalled.

“I just remember getting really flushed and hot on the inside,” she said. She ditched her prepared speech and told her own story instead. It wasn’t drug-policy reform, but it painted a startling, intimate picture from inside the U.S.’s incarceration crisis. That vulnerable moment helped accelerate a growing movement, and it raised Winn’s profile as an advocate for prison reform. Her standing ovation was just the beginning.

• • •

A decade before, Winn’s life looked very different. An Atlanta native and a Grady baby, she was born to a mother who struggled with substance issues. Winn went on to earn her degree and become an OB-GYN nurse, but, in 2008, she was arrested and indicted on 20 counts of healthcare and bank fraud. During intake, she discovered she was six weeks pregnant.

Still, Winn was shackled during transport to and from court dates. “It was one thing to cuff me; it was another thing to wrap that big chain around my belly,” Winn says. “I made a mental note that I was gonna say something to the medical [staff].” She never got the chance. Climbing into a prison van that afternoon, she fell; a few days later, she started bleeding. Winn ended up miscarrying inside the detention facility, having never received—as she would later allege, in testimony before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights—“any formal or proper prenatal care.”

After her release in 2013, Winn joined advocacy groups and connected with other formerly incarcerated women to support prison-reform bills and advocate for antishackling legislation at a national level. In 2017, following her impromptu speech, she started a petition asking Congress to pass the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, which would prohibit shackling and solitary confinement for pregnant or postpartum incarcerated women. In just a month, the petition gained 100,000 signatures, and Winn’s efforts caught the attention of Senator Cory Booker, who invited her to Washington to participate in a roundtable. The bill didn’t pass, though some of its provisions—including a ban on shackling pregnant people in detention—were enacted as part of a separate criminal justice–reform bill signed into law in 2018. Still, the ban only covered people incarcerated in federal facilities—not the vast majority of women held in state prisons and local jails.

Winn shifted her focus to the state level—starting in Georgia, where she helped spearhead the successful bipartisan 2019 bill that prohibited the shackling of pregnant women in prisons and jails. Versions of it have since been adopted in 19 states.

She also founded RestoreHER, a policy-advocacy and reentry organization that offers comprehensive wellness, rehabilitation, and leadership programs to formerly incarcerated women. In addition to advocating for prison reform, the organization supports women who are struggling to reenter society and rebuild their lives under the burden of a criminal record. RestoreHER offers training on self-care, anger management, and restoring personal relationships; helps women find union and nontraditional jobs where their background is less important than their skill set; hosts classes with realtors who can guide women toward homeownership; provides financial literacy and investment workshops; and offers advocacy workshops that prepare women to jump into the political ring alongside Winn.

“We teach them about how a bill becomes a law, voting, how to become a legislator or lobbyist,” Winn said. “So, if they want to make change about things that they care about in their communities, they are knowledgeable of how to do those things.”

Today, Winn’s goal is to end prison birth completely. For the last two legislative sessions, she and State Representative Sharon Cooper have introduced the Georgia Women’s CARE (Childcare Alternatives, Resources, and Education) Act, which would require pregnancy testing for all arrested women within 72 hours of their detention and allow them to immediately bond out if the test is positive; it also mandates that pregnant women who are convicted and sentenced to serve time be allowed to defer their prison sentence until at least six weeks postpartum.

Progress has been steady but slow, perhaps in part because, according to Winn, people don’t readily empathize with incarcerated women. But Winn, who practiced in women’s healthcare for more than 10 years, says her advocacy is not only for the mothers: “Regardless of what you think about women, what you think about incarcerated folks, or what you think about people of color, when it comes to babies, we all agree we want safe, healthy babies.”

This article appears in our March 2022 issue.

[ad_2]

Source link