‘Learning To Swim At 24 Taught Me An Important Life Lesson’

[ad_1]

It was the summer of 2018. My sister, cousin, and I were aboard a motorboat with seven other wide-eyed tourists hoping to catch a glimpse of the sunken statues off the coast of Isla Mujeres, Mexico. As we pulled away from the beach, I watched the celeste-hued water transform into a midnight blue and realized I could no longer rely on my fragile safety net—the knowledge that I’d be able to see my feet on the ocean floor. This was deep sea.

After about 15 minutes, our captain stopped the vessel and began to distribute the essentials alongside his assistant: life jackets, flippers, and goggles.

“Anyone who wants to get in and see the statues, now’s your chance,” he announced in Spanish, our shared mother tongue.

While my sister and cousin happily obliged, I remained seated—paralyzed by an unshakable fear. As I gazed into the navy-colored sea, I couldn’t escape the intrusive thoughts plaguing my mind: What if a ferocious current comes by and pushes my body miles away from the safety of this vehicle, and I’m never to be found? What if I’m bitten by a great white shark and there’s no one there to save me? What if I drown?

While I’m aware of the human body’s natural buoyancy in saltwater, I’m also conscious that the ocean will not hesitate to swallow one whole at the first sign of fear. In other words, I wasn’t about to risk it.

I’ve never been a particularly strong swimmer.

While I’d participated in an entire year of swimming lessons in the sixth grade—a rare opportunity for a low-income Black girl attending a West Bronx public school—sometime between the start of puberty and the beginning of adulthood, I had become increasingly aware of my own mortality. For me, this awareness largely manifested in a fear of drowning. When it comes to water-based activities, I prefer to stand comfortably in the shallow end.

And so, one by one, my boat mates made their way into the water. But I stayed onboard. As my family members and the other tourists followed the captain to see the life-sized sculptures which sat 30 feet under the surface, I began to viciously sob—failing miserably to hide my shame from the deckhand watching me as I swallowed my own salty tears.

I’ve always felt a deep connection to bodies of water. Whenever I feel overwhelmed, I search for a waterfront—a rarity in my concrete jungle home of New York City. My affinity also makes sense, since being in or near water has been linked to a reduction in stress, alleviated anxiety, and a boost in overall mood, according to licensed therapist Shontel Cargill, LMFT.

Yet, the visceral pain I felt that day from not being able to jump freely into the water is not something even I truly grasp. It felt like I’d tapped into a deep source within me—an ancestral struggle, almost. It was like I could hear the synchronous wails produced by my collective bloodline, begging for freedom from the forces that kept them shackled to the island of La Española—fearing yet worshiping the water gods.

It’s a common racist trope that Black people can’t swim.

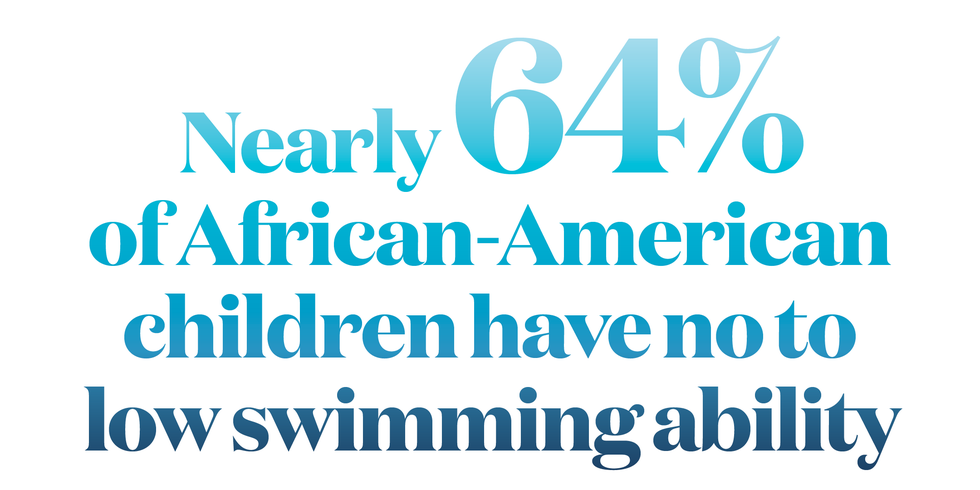

But it’s hard to ignore this one’s startling reality. Nearly 64 percent of African-American children have no to low swimming ability, compared to 45 percent of Hispanic children and 40 percent of Caucasian children, according to USA Swimming. Moreover, Black children drown at rates three times higher than white children, per the CDC.

And it’s not just children who are affected. Black people, in general, drown at higher rates than any other demographic, says Paulana Lamonier, the founder and CEO of Black People Will Swim, a mission-based program empowering Black and brown people to be more confident in the water. I first learned about Paulana and her mission after reading a feature on her on CNBC, and knew that when I decided to begin my swim journey, it would be with her.

“The reason why it’s important for us to teach people these life-saving skills is simply that: because it is a life-saving skill,” she tells me. “We’re really giving people that chance to dream again; the chance and opportunity for freedom. When you’re on vacation, you no longer have to sit poolside—you don’t have to be scared to jump.”

Twenty minutes past noon on Saturday, May 20, 2023, I went to my first swim class.

I arrived at CUNY York College’s Health and Physical Education Building where classes for Black People Will Swim’s spring 2023 program were being held. By the time I reached the 25-meter swimming pool, class was already in session.

Paulana, a warm yet commandeering figure, was teaching the class, and invited me to join. As I slowly and awkwardly slid my way into the pool’s shallow end, I took in the expressions around me. There was a variety of ages in our adult-beginner course, which was made up of all Black women. Young 20-somethings, like myself, women in their 30s and 40s, and even a few Aunties—elders, often mature women over the age of 50.

Our first lesson started with a breath. We were to learn how to breathe underwater.

One by one, Paulana went around asking each of us to hop down into a squat until our fingertips touched the pool floor. Once there, rather than sucking in air through our nostrils, we were to expel that air by blowing bubbles—holding in the remaining oxygen in our mouths. When my hands touched the bottom of that pool and I was surrounded by blue I felt—if only for a second—at home. If only I could breathe underwater, I thought, I would never leave.

“The water was like my getaway,” says Maritza McClendon, a 2004 Olympic silver medalist and the first Black female to make the U.S. Olympic swim team. “Every time I get in the water, I’m in my happy place—I’m in my element.”

McClendon—who, after being diagnosed with scoliosis, began swimming at the age of six per her doctor’s recommendation—has always found solace in the water, even when the pressures of competitive swimming weighed her down.

“When I got in the pool, it was like I went into an oasis and forgot about everything—it was just me and the water.”

As I re-emerged from the pool after that first drill, I suddenly became aware of my senses. The silence from being submerged disappeared, and I was met with the noises around me.

To my right, one of my classmates—an older woman perhaps in her mid-60s to early 70s—was holding onto the edge, quietly blowing bubbles to herself as the rest of the class moved onto the next lesson.

I pondered what experience may have caused her to develop this palpable fear, and ultimately lead her here today. I also wanted to grab her hand and walk her to the middle of the pool, so we could float together like two otters, holding on tight to ensure the other wouldn’t float too far away, and she could share some of the joy I felt.

The truth is, part of the reason why many Black and brown Americans don’t know how to swim today is a result of racial and class discrimination.

“There were two times when swimming surged in popularity—at public swimming pools during the 1920s and 1930s and at suburban swim clubs during the 1950s and 1960s. In both cases, large numbers of white Americans had easy access to these pools, whereas racial discrimination severely restricted Black Americans’ access,” wrote Jeff Wiltse, a historian and author of Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, in a 2014 paper published in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues.

The systemic impairing of Black Americans’ ability to swim—thanks to poorly maintained and unequal swimming pools, private clubs that barred Black members, and public pool closures in the wake of desegregation—meant that swimming became a “self-perpetuating recreational and sports culture” for white Americans, says Wiltse. Black communities struggled to literally and metaphorically get a foot in.

“[Swimming] is a predominantly white sport,” says McClendon. (FYI: Of the 331,228 USA Swimming members, less than 5 percent are Black or African American, according to the 2021 Membership Demographics Report.)

“Growing up, I was definitely one of the few at every single swim meet, and even on my swim team,” McClendon recounts. “As early as nine years old, I remember finishing a race in which I got first, and walking past a parent who said, ‘You should go back and do track or basketball. What are you doing here?’ Sort of questioning why I was in the sport. If anyone else would’ve won the race, they would’ve been congratulating them.”

While most of McClendon’s career spans the 1990s and early 2000s, she says instances like this still happen today.

I missed the next three weeks of classes, so by the time I walked into my second swim session, I felt energized yet daunted.

As soon as I got in the pool, I asked my classmates about their reasons for joining the Black People Will Swim program.

One woman shared that she wanted to learn how to swim because she’s the only one in her family that couldn’t and she had a seven-month-old son: “If he’s drowning, I want to be able to save him,” she tells me.

The second woman I spoke to said almost drowning twice pushed her to want to learn.

Unsurprisingly, most of these reasons pertain to survival. Swimming, at the end of the day, is a skill needed to live; it’s an ability and privilege that so many take for granted.

At the start of that second class, I was anxious. I had missed so much during my time away, and we were at the point of the program where everyone was expected to navigate the 14-foot end of the pool. Our first lesson of the day: butterfly backstrokes. I tried my best to prolong my turn by generously offering that my other classmates go ahead of me, but eventually I had to go.

As I positioned my feet on the wall, held onto the edge of the pool, and laid my head back, I silently repeated to myself, You got this! You are a child of the water. You will not drown. “Ready?” asked the instructor who was teaching my class. With one deep breath, off I went.

As soon as I started kicking my feet and pushing the water forward with my arms, I was making headway. It felt so natural, like muscle memory. Perhaps those middle school swim lessons did teach me something. After about five strokes, I was ordered to stop so the next person could demonstrate if they were ready to move on to the next step.

Swimming is easy enough when you know you can safely land on your feet the moment you start to panic, but once the depth of the pool is above my own height (at 5’4″), I no longer feel at ease. So you can imagine my nervousness when the instructor said we were about to backstroke the entire 25-meter pool.

As I prepared for that feat on the wall, I recounted the memory of that fateful summer of 2018, when I was too afraid to jump off the boat without a lifejacket. Then there was another memory: 11-year-old Naydeline, unafraid to jump into the deep end. Instead, exhilarated by it.

“Ready?” asked the instructor.

“Yes.”

Off I went, rapidly backstroking across that 25-meter pool. I was making headway, but as I reached the 12-meter mark, I stopped. I was beginning to swallow water, and the chlorine-tinged liquid filling my throat made me panic. I was no longer swimming, but sinking. I quickly grabbed the nearest lane rope to stabilize myself.

“What happened?” asked my instructor. “You were doing so well.”

“I panicked,” was all I could say. The intrusive thoughts had started to pour in as soon as I sensed the depth of the pool change from six feet to eight feet to 10 feet: You’re drowning, you’re drowning, you’re drowning, and my anxiety took over.

It took a few seconds to catch my breath, but then I turned to face the deep end of the pool. I realized there was no getting out of this—I had to keep going. With my instructor situated behind me to catch me if I began to drown, I shut my eyes and inhaled for three counts, exhaled for three counts, again and again. Ready?

I was off once more. I didn’t stop until I hit the end of the pool.

A month after the end of the swim program, I headed out on a trip to the island of Aruba.

The schedule was filled with walking tours, parasailing, and an exploration of one of the island’s many natural pools.

The author parasailing off a boat at Palm Beach, Aruba.

On the second to last day, we kayaked across a small portion of the Caribbean Sea to go snorkeling. There would be coral reefs, parrotfish, and lobsters. I opted out.

I wasn’t confident that I wouldn’t start to panic and drown. So, while the rest of my tour group and the instructor went ahead, I stayed seated on the dock. As I looked out at the expansive sea around me, noticing how the colors transitioned from celeste to navy, I breathed in deeply: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4. I was trying my best not to cry.

Our reserved, yet warm tour guide had also stayed behind. He claimed he was tired of beautiful beaches and ocean views—they didn’t impress him, he said. After noticing that I had been sitting alone on the dock for what felt like half an hour, he came to sit next to me. I told him about my deep affinity for the sea, but also how much it terrified me.

“The trick to swimming,” he said, “is letting go of fear. […] The water will do most of the work for you. It’ll hold you up, but only if you let it. You must remain calm, and trust yourself.”

Perhaps that is the missing puzzle piece: trust. Trust in the water, but most importantly, trust in myself. Trust that I could keep myself alive, and the water would help me—if I let it.

Assistant Editor

Naydeline Mejia is an assistant editor at Women’s Health, where she covers sex, relationships, and lifestyle for WomensHealthMag.com and the print magazine. She is a proud graduate of Baruch College and has more than two years of experience writing and editing lifestyle content. When she’s not writing, you can find her thrift-shopping, binge-watching whatever reality dating show is trending at the moment, and spending countless hours scrolling through Pinterest.

[ad_2]

Source link