More than half of all African-Americans have high blood pressure under new diagnostic guidelines

[ad_1]

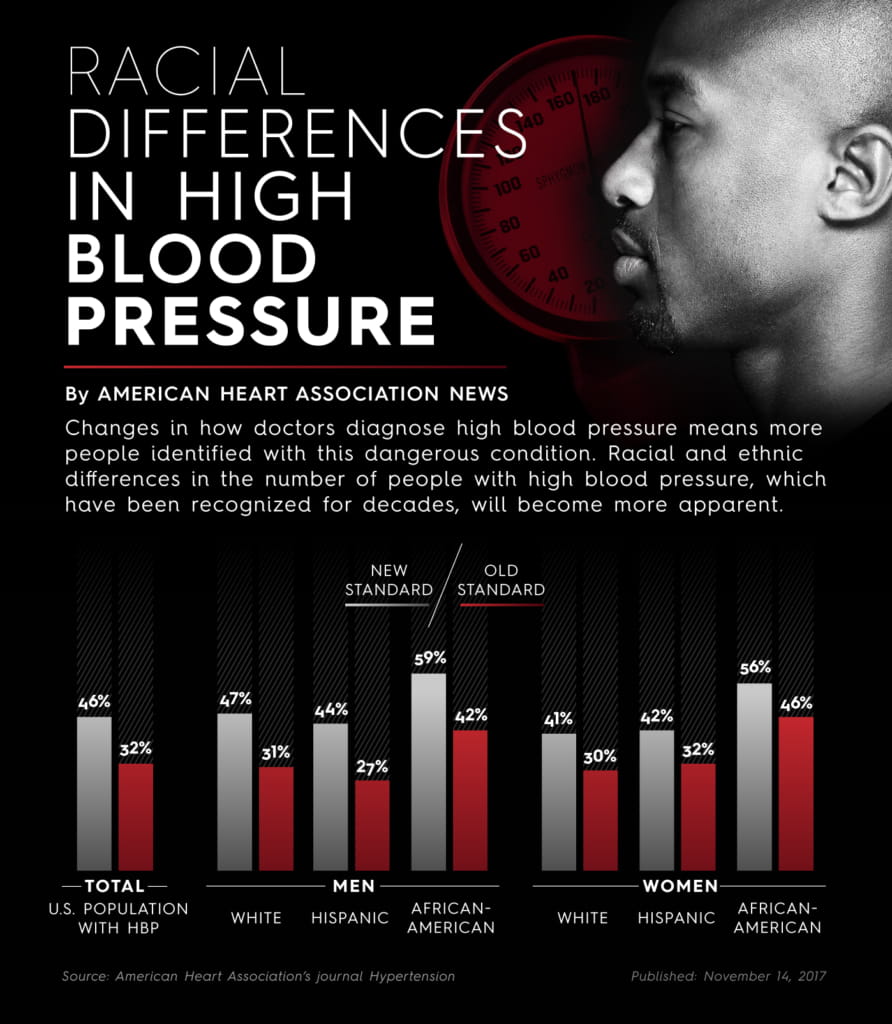

ANAHEIM, California — Well over half of all African-American adults will be classified as having high blood pressure under new streamlined diagnostic guidelines released this week, illuminating the heavy burden of cardiovascular disease in the population.

The guidelines change the definition of high blood pressure – also called hypertension – to begin when measurements show a top number of 130 or a bottom number of 80. That changes from 140/90, where it had been since 1993.

With this change, it is estimated that 59 percent of all African-American men will be classified as having high blood pressure, up from 42 percent. Fifty-six percent of African-American women – who had the highest rate previously at 46 percent – now have high blood pressure. Forty-seven percent of white men and 41 percent of white women have high blood pressure.

“Earlier intervention is important for African-Americans,” said Kenneth A. Jamerson, M.D., a guideline author, cardiologist and professor of cardiovascular medicine with the University of Michigan Health System. “Hypertension occurs at a younger age for African-Americans than for whites. By the time the 140 over 90 is achieved, their prolonged exposure to elevated blood pressure has a potential for worse outcome.”

Heart disease also develops earlier in African-Americans and high blood pressure plays a role in more than 50 percent of all deaths from it. African-Americans have a higher rate of heart attacks, sudden cardiac arrest, heart failure and strokes than white people. In addition, their risk is 4.2 times greater for end-stage renal disease, which often progresses to the need for dialysis multiple times a week and ultimately to kidney transplantation or death.

“Hypertension has been a blight on the African-American community for many, many years. It’s time for us to get over it,” said Kim Allan Williams, Sr., chief of cardiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. “People need to get screened and get care.”

The new guidelines are expected to offer new ways for medical providers to work with patients, who will be asked to modify their lifestyle by quitting smoking, drinking no alcohol or moderate amounts, eating a healthy diet, and exercising regularly.

“You may not have to take a pill,” said Jamerson. “These discussions are more work for a provider, but it’s great for the patient. They’re brought into the process.”

If medicine is needed, the new directions are to treat earlier and more aggressively to get blood pressure into the normal range right off the bat.

“Our data shows controlling early works,” Jamerson said.

That’s different from the old-school way of prescribing one drug and slowly upping the dose or adding other meds if the patient doesn’t reach the target.

“We have struggled at every level,” Williams said about African-Americans’ high blood pressure. “Identifying who has it, once identifying, getting them treated and once treated, getting them controlled.”

The guidelines are also offering race-specific treatment recommendations by addressing drug efficacy in African-Americans. The guidelines point out that thiazide-type diuretics and/or calcium channel blockers are more effective in lowering blood pressure in African-Americans when given alone or at the beginning of multidrug regimens.

Jamerson said there is no downside to more aggressively treating high blood pressure from the start.

“If one takes the long view, then everyone should appreciate this approach,” he said. “The cost of medications to treat more people is small, when compared to the cost of a stroke, cardiovascular disease or heart failure. It’s a no-brainer.”

I

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].

[ad_2]

Source link