One family’s intimate history with the implications/significance of the abortion legislation

[ad_1]

When my great-great-grandmother knew she needed to end her pregnancy, she found someone to give her an abortion deep in the woods of segregated Washington, D.C, lying on the ground.

And now that the Supreme Court has dealt its final blow to Roe v. Wade, there are people in America prepared to do what my grandmother did – splaying out mason jars, aquarium tubing, and plastic syringes on beach towels. In this not-so-dystopian reality, I could find myself doing the same thing.

Last October, I was assaulted by a man I knew from college. I was asleep in my bed when it started. Crying into my dad’s shoulder weeks after, I wondered if I’d ever be able to move on from the feeling of waking up to someone’s shoulder blades spreading over my body, to their hands gripping my ribcage.

If I had become pregnant, and the assault occurred in one of the many states where abortion will now be illegal or severely restricted, I’d be legally compelled to carry the pregnancy to term. But no amount of state laws could keep me from terminating that kind of pregnancy. I am speaking entirely for myself when I say that it would destroy me. I would retreat to the woods as my grandmother did, as many will do, motivated by fear and desperation.

This is the world we are about to enter – if we have not already arrived. Two-thirds of Americans don’t want to see Roe disappear. Another two-thirds want to preserve abortion rights in cases of sexual violence. Yet, we have rolled back the clock against the majority’s will. We are witnessing the regression of civil rights that an entire generation of women, transgender and nonbinary people have never lived without.

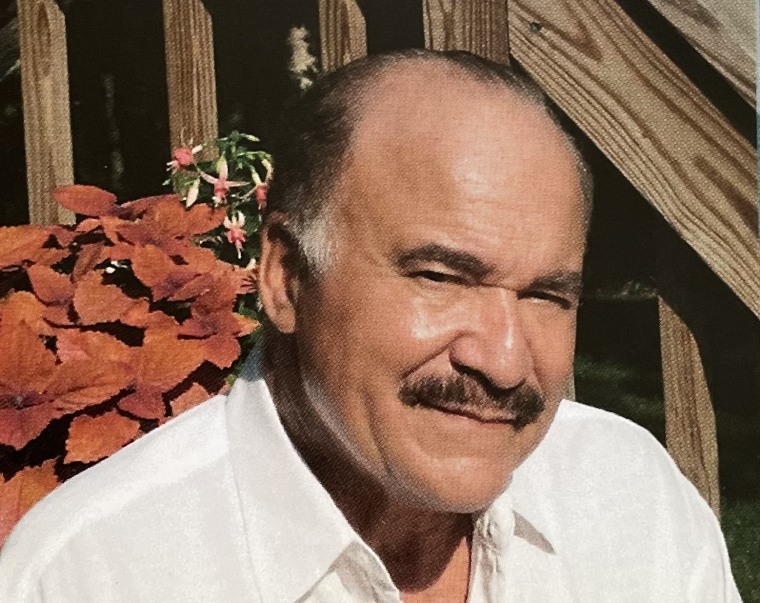

Abortions, legal or not, are a fact of life. The earliest record of a successful abortion is more than 4,000 years old. Under the care of a physician, they can be life-saving health care. So too, are they inextricable from a person’s freedom to determine their own destiny. I learned this from my late uncle, Dr. Kenneth Edelin, a Boston physician who sacrificed his own reputation and security to safeguard a young woman’s legal right to an abortion.

It was Uncle Kenneth who made me aware of my second grandmother, who was his mother’s mother. And it’s his life’s work that comes into sharp focus for me today.

Nine months after the Supreme Court handed down its decision on abortion in 1973, a Black teenager and her mother came to him asking for help terminating the 17-year-old girl’s unwanted pregnancy.

Yvonne (a pseudonym he used in his memoir Broken Justice to protect her identity) was a high school senior. She wanted to go to college. She wanted to have a career and have children someday, just not now.

He could hear her mother’s anxiety that day at the Boston City Hospital: “I can’t take her home pregnant,” she told him. “Vonnie can’t come home pregnant. She can’t continue this pregnancy. Her father can’t know about this, Dr. Edelin.”

Uncle Ken understood that he would perform legal abortions during his residency. This was underscored by an experience he had in his third year of medical school where he’d witnessed a teenager die of sepsis after an illegal abortion – either by a knitting needle or coat hanger.

“As I learned to do abortions, I learned that they were never easy for me or for any of the residents who did them, but I understood the impact unwanted pregnancy could have,” he wrote. “I believed that the decision to have or not have an abortion should be left up to each woman. I believed that poor, Black women should have that choice, too.”

So, Uncle Kenneth honored the wishes of Yvonne and her mother. But this was in the Irish-Catholic city of Boston in the 1970s, and the racial and political climate was ripe for turmoil. Although Roe was the law of the land, Edelin was prosecuted for manslaughter. And he was indicted – by an all-white, predominantly male, and overwhelmingly Catholic jury.

“In Boston, it was the perfect storm,” he told the Boston Globe in 2007. “It was the religious climate; it was the racial climate.”

The case had a chilling effect on legal abortions nationwide. As The New York Times noted in 1976, physicians across the country “refused to perform abortions in the middle stages of pregnancy for fear that they, too, might be prosecuted.”

The case was overturned two years later by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, stating that there was insufficient evidence to prove any wrongdoing. Uncle Ken remained in the business of saving women’s lives, becoming chairman of the board of Planned Parenthood.

I remember looking up at him on stage at the March for Women’s Lives in 2004 as he said:

“We knew that when abortion is illegal, it is African-American women — especially young Black women — who suffer most, who are injured by illegal abortions and who die from them,” he said. “We cannot let our government turn back the clock so that women, especially Black women, are hurt and die.”

I was 8 years old at the time, holding tight to my mom’s hand on one side and my grandmother’s on the other. Uncle Ken was my grandmother’s younger brother, and watching him stand trial for manslaughter had dramatically changed her outlook on justice and civil rights. She, too, dedicated her career advocating for reproductive rights at Planned Parenthood.

I didn’t understand the concept of sex, let alone abortion. But I understood that I was born with rights and liberties the generations above me had to acquire and protect through a painstaking fight.

But for all of the progress and sacrifices over the last 50 years, the coming years may tell a different story.

In September of last year, Texas codified an abortion ban that empowers citizens to sue anyone who helps a patient receive an abortion after the six-week mark, from the doctor who performed the abortion down to the bus driver who drove the patient to the clinic. Seven states immediately copied the legislation, introducing it in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Missouri, Ohio, and Oklahoma. My Aunt Barbara, who witnessed the trial unfold, warned that if it were to take place today, “it would be far worse.”

“Her mother, the bus driver, anybody that helped becomes liable. It’s just so unbelievable,” she said. “I’m not sure he would win on appeal today.”

My cousin Corinne, Uncle Kenneth’s youngest daughter, said she might consider moving from her home in Atlanta because of the state’s abortion ban.

“It’s one of those things where I really do have to think long term about when I have my own family, and it’s the right move to raise them in a state where their rights are limited – or virtually zero,” she said. “Especially if I have daughters, do I want them to live in a state where they don’t have this right and this choice?”

When Justice Alito’s draft opinion leaked in May, my cousin Kimberley, Uncle Ken’s eldest daughter, told me she could feel her dad’s pain. “I felt the pain he had endured,” she said.

“When I was a bit younger than you are now,” she explained, “I thought that the old racist, misogynist, and patriarchal ways would just die out. But they don’t die out. They’re built into our institutions. They teach them to the next generation, so we’re always going to have to fight these battles.”

If Uncle Ken were with us today, and if my grandmother’s memory had not been lost to dementia, I know they would be enraged. But I also know they would not be idle. They would be marching. They would be agitating, and they would be prepared to make the same sacrifices all over again. The right to choose is too precious of a civil right to lose, and we cannot afford to go back into the woods.

[ad_2]

Source link