Post-pandemic party’s over as Americans shun cognac

[ad_1]

When New York’s nightlife reopened as pandemic lockdowns eased, partygoers wanted to drink one thing: cognac. “Everybody was ordering excessive amounts of bottles . . . at one point there was a shortage of Henny,” said club promoter Frankie Banks, referring to LVMH’s Hennessy brand cognac.

But the party is now over. After a three-year boom, US demand for cognac has slumped, with the French groups that dominate the market — LVMH, Rémy Cointreau and Pernod Ricard — each reporting declining sales in their third-quarter earnings. The trend matches a slowdown in the broader market for luxury goods.

Premium alcohol sales rocketed during Covid lockdowns as bored consumers stuck at home with extra savings splashed out on pricier spirits. This continued as bars reopened.

But drinkers are now dialling back on spending amid worries about the economic outlook with aspirational spirit brands becoming one of the first luxury categories to moderate.

“We are crossing into territory where the savings are gone, the support is gone,” said Spiros Malandrakis, spirits analyst at Euromonitor. “It looks like a hangover after the great party that followed the pandemic recovery.”

Export volumes of cognac, a brandy produced from white wine grapes in western France, fell 18.9 per cent between August 2022 and the end of July this year, according to the cognac producer’s association UGVC.

The US is by far the largest consumer of cognac, importing more than half of bottles produced, according to the Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac (BNIC).

Half of all cognac in the US is drunk by African Americans, a demographic that has been disproportionately affected by the cost of living crisis, according to analysis by Bernstein.

The skew to African American consumers is in part due to the fact that French spirits producers ignored the segregation mandated by America’s Jim Crow laws and “cultivated the African American market segment in ways that other producers did not,” said David Crockett, professor of marketing at the University of Illinois Chicago.

French spirits producers at the time marketed to Black-owned and targeted publications. As early as the 1970s the advertisements conveyed a message of upward socio-economic mobility, said Naa Oyo Kwate, a sociologist at Rutgers University, with campaigns running in magazines such as Ebony. She highlights a spread from one 1983 edition, showing a glamorous woman pouring a drink with the tagline: “I assume you drink Martell”.

Cognac became a status symbol in night clubs in the 1990s and 2000s, when rappers introduced cognac brand names in lyrics, like Busta Rhymes’s and Diddy’s 2001 hit, “Pass the Courvoisier,” which led to a spike in sales of the cognac, which is owned by Japan’s Beam Suntory group.

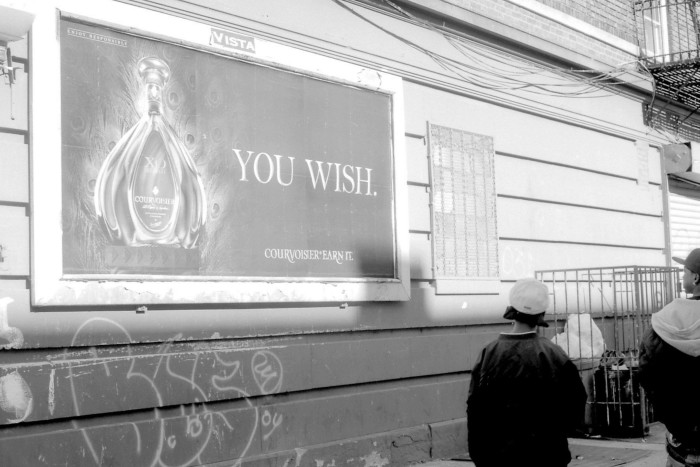

Ads targeting Black Americans throughout the 2000s featured taglines such as, “You wish”, “Upgrade” and “Envy is so unattractive”, Kwate said.

A cognac market dominated by four labels — Hennessy, Martell, Courvoisier and Rémy Martin — expanded further as Black celebrities became brand owners. Ludacris launched Conjure Cognac in 2009 and Jay-Z launched D’Ussé in 2012.

While sales in categories like whisky and champagne dropped in 2020, cognac was one of the few spirits that did not decline during pandemic lockdowns as consumers continued to drink it at home, according to Euromonitor.

Anthony Brun, president of UGVC, said that the downward trend for cognac in the US was consistent with other drinks categories.

“There is no disenchantment with the cognac as a product or existential questions to be asked there. We are suffering, like others, the consequences of the end of Covid, the war in Ukraine, inflation, which have all had an impact on the world economy,” he said.

At LVMH, the luxury industry’s bellwether, the wine and spirits division was the only one where sales fell in the first nine months of the year compared to the same period in 2022. “Demand [for cognac] is pretty soft in the US,” LVMH CFO Jean-Jacques Guiony told analysts.

The post-pandemic hangover has been exacerbated by the effect of destocking, said Brun; at the height of the party, retailers became overexcited and ordered more to meet rising demand. Waiting for the excess inventory to be sold has weighed on sales, but he expects inventory levels to be back in balance by the end of the year or early 2024.

Speaking to investors following the third-quarter trading update last week, Rémy Cointreau’s CFO Luca Marotta said it was not clear what proportion of the declines were a result of destocking and how much was due to competition from discounting activity by its key competitor in the cognac market, which he did not name but is LVMH.

LVMH has ramped up promotions of its Hennessy brand to attract US consumers hit by the cost of living crisis, according to analysts. Marotta said intensive promotion by its competitor was “destroying value” and damaging consumer perception. LVMH did not respond to a request for comment.

Bernstein analyst Trevor Stirling said consumers were likely trading down to a more affordable label in the LVMH stable. Rémy Cointreau only sells the more expensive cognacs in the US — Very Superior Old Pale and Extra Old — while LVMH sells a third, cheaper cognac, Very Special.

Cognac’s popularity may also be threatened by tequila’s booming popularity, which has in turn also been boosted by celebrity endorsements. African Americans who historically have not drunk tequila are starting to move into the category, said Stirling.

Part of tequila’s appeal is its lower price point said Aleen Tran, a business analyst at Pernod Ricard in California. Tran, who focuses on Martell, said that with inflation, “prices have gone up across the board, but tequila is still cheaper than cognac”.

“Cognac is dying a very slow death in New York right now,” said Christopher Collins, director of events at nightclubs Taj and Katra Lounge. “Tequila has taken over the whole hip hop scene.”

Euromonitor’s Malandrakis said the cognac downturn raised alarm bells about the health of the economy, and resilience of the US consumer.

“You can’t have people continuing to buy the most premium alcohol categories in this inflationary environment — something didn’t make sense,” he said. “What we’re starting to see is the inevitable.”

[ad_2]

Source link