The Latin America Early Career Earth System Scientist Network (LAECESS): addressing present and future challenges of the upcoming generations of scientists in the region

[ad_1]

Regional environmental climatic issues and their consequences in LAC

The impacts of climate change in the LAC region are observed in the atmosphere/hydroclimate, oceans, and cryosphere which directly impact the biosphere. They have been identified and quantified as altered precipitation regimes, higher atmospheric and sea-surface temperatures, higher risks of droughts, increasing aridity, glacier mass loss, relative sea-level rise, higher intensity of tropical cyclones, marine heatwaves and significant loss in biodiversity1,2,3. More specifically, LAC contributes 10% of the global CO2e emissions, where land use and change forestry is the major contributor4. This is mainly related to deforestation and forest fires due to agricultural, livestock and urbanization expansion processes, especially in the Amazon Forest5. In Central America significant warming trends between 0.2 °C and 0.3 °C per decade have been observed in the last 30 years. Long-term observed precipitation trends show an increase over south-eastern South America and a decrease in most tropical land regions. On the Atlantic coast of South America, the rate of sea-level rise is higher than the global mean (~3.6 mm yr−1) and is lower along the Pacific coast (2.94 mm yr−1). Similar results were observed on the Caribbean Sea/Gulf of Mexico side (3.7 mm yr−1) and the Pacific side (2.6 mm yr−1)3. CO2 absorption by the seawater also results in lower pH values, which is known as ocean acidification. In South America, ocean acidification is affecting the Humboldt Current, one of the world’s four major upwelling systems, provoking negative impacts on key ecosystems6. Moreover, recent studies showed that the rate of glacial mass loss in the entire Andes Mountains amounted to −0.72 ± 0.22 meters of water equivalent y−1 from 2000 to April 20187. As the Andes glacier volume loss and permafrost thawing increase, there will be significant reductions in river flow and potentially high-magnitude glacial lake outburst floods8. The coupling between Earth-Climate systems should also be considered, for example: it has been demonstrated that the Amazonian biomass burning reaches the Andean glaciers, which accelerate its melting9, and consequently raises sea-levels. This directly affects coastal areas like the Caribbean, Guatemala, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, among others. All of these changes result in biodiversity losses4,10. In LAC, biodiversity hotspots and areas of high endemism are abundant. The LAC region contains about 60% of the global terrestrial life and diverse freshwater and marine species, 12% of the world’s mangrove forests, the most extensive wetlands, and 10% of the world’s coral reefs. However, there has been a decline in species abundance and a high risk of species extinction11,12.

When combined and extended into the economic and social dimensions, all these impacts provide excellent conditions to exacerbate socio-economic distortions and inequalities in the LAC region1,13. The socio-economic conditions of the region, characterized by poverty and high inequality, increased the vulnerability to these scenarios14. For example, considering the importance of the agricultural sector in LAC in producing food and ecosystem services for the entire planet15,16, the climate change impacts will affect food production, processing, storage, transport, and distribution, which could impoverish the regional economies1,15,17. In addition, populations located in the remote areas of LAC, indigenous people, and communities dependent on agricultural or coastal livelihoods will be especially at risk18,19. Additionally, climate change increases vector and viral diseases’ development and spread, resulting in worldwide consequences20,21,22.

General public information and perception about the environmental and climatic impacts

General public information and perception are essential to combat climate change, not only by changing their lifestyles but also by voting for decision-makers that can promote environmental protection policies. In the past five years, there has been increasing awareness (from 56 to 67%) of climate change as a threat23. Eighteen LAC countries highlight the importance of climate change for the population. On average, 83% of the people in these eighteen countries agree that anthropogenic activities are the leading cause of the impacts, and 70% agree that mitigation and adaptation should be a priority24. Most individuals in LAC see the issue of climate change as a serious threat25. This can result from local communities witnessing regional impacts, as described in Section 1.1. This awareness is dependent on the regional historical context and level of education24. Education is one of the main drivers of public engagement. However, in recent years the rise of the scientific scepticism movement as part of climate change denial is one of the reasons why science is not recognized as important by both the public and the governments24. A recent study by Soh (2019)26 notes that in LAC the relative distancing of the general public from the benefits of scientific discovery has made science and technology funding an easy political target for fiscal restraint in an economic downturn. Therefore, EC scientists have had to change their approaches to reach the public and change the perception of environmental and climatic issues. By enhancing EC networks like LAECESS, these new approaches can be addressed collectively.

Although the local political context does not promote an environment to debate and shape new attitudes25, the increasing perception of the severity of climate impacts needs to be aligned with concrete actions to minimize climate change impacts. Mitigation strategies can improve energy generation, urban transport, agriculture, food distribution, and population health with public support. The World Economic Forum27 highlighted the focus on expanded investments in research and innovation to allow new markets for the future, embracing diversity and inclusion. Thus, science should be transparent, easy to understand, and integrated into life.

LAC early career challenges

While many Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region researchers aim for a high level of research, they are constrained due to lack of funding support, limited access to grant opportunities, substandard laboratory facilities and equipment, low salaries, and lack of tenure security28. From 2010 to 2019 the number of students enrolled in higher education programs increased by 38%, while the amount of money spent for the same period was, on average, 1.3% of the gross domestic product29. Of the total number of graduates during 2019, 35.7% were from Education, Natural sciences, Technology, and Engineering, while 64.3% studied Arts, Humanities, Business, and Welfare courses related, considering the entire LAC29. Argentina and Puerto Rico are the countries with a higher percentage of graduates in the Natural science field.

There are not enough research positions in LAC scientific institutions to absorb outstanding investigators. According to the International Labour Organization, millions of formal working positions were lost in Latin America during the last four years, with an impact on women and youth30. The employment rate recovery occurs for informal jobs (i.e., no official contract, few or absent benefits, no insurance, irregular working hours, non-paid extra hours). In turn, brain drain takes place31. This type of migration, where highly skilled professionals leave their home countries seeking for better working conditions just increased over the years32. In average, 10 to 40% of the LAC brains went to the U.S. over the last five years33. Many researchers, especially EC scientists, decide to leave the region, looking for proper venues and adequate support34. Researchers find more freedom, stability, resources, and grants to implement their scientific endeavours in many developed countries abroad, especially if they have the chance to perform study or training during master’s or Ph.D. degree35.

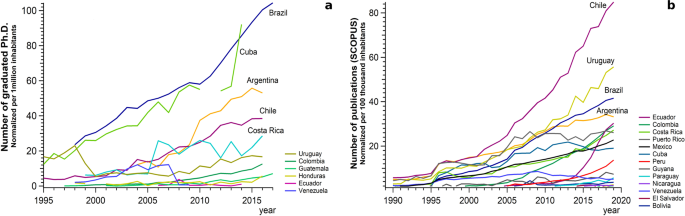

During the 2000’s, a dynamic internal movement was observed with the increase of intraregional educational policies, regional mobility programs and governmental scholarships for higher education/training and work exchange within LAC, but the numbers have been decreasing since 201736. The number of graduates in LAC increased by 42% in one decade29, with the highest numbers from Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina, respectively (when data normalized per 1 million inhabitants)29,37 (Fig. 1a). The number of publications followed the same tendency by considering the American continent (Fig. 1b). Over the last century, the overall publications on the general climate topic were primarily done in the U.S. (83%), with only 17% of the publications spread over LAC38. The total number of scientists in LAC is six times lower than in U.S.39. The low scientific productivity in the LAC region is not the result of a lack of excellence or creativity. Instead, it reflects the absence of a long-term scientific policy that is a common factor in most LAC nations28. LAC earth system science EC researchers are vital for tackling the regional issues previously mentioned, as they have the expertise of these issues with a global perspective combined with a cultural background that allows the applicability of a worldwide scientific issue to the regional and local context35,40,41. For example, previous experiences in Africa42,43 showed that research done without local expertise might exclude crucial local knowledge, not be locally relevant or applicable, or miss local-based solutions of potential global importance.

Number of graduated Ph.D. in time normalized per 1 million inhabitants in a and number of publications in SCOPUS in time normalized per 1 million inhabitants in b. Data are accessible at Red RICYT37.

Due to the immediate impacts caused by climate change in most areas in LAC, in this paper, we call for a comprehensive research system and more significant support for the EC of LAC researchers, which is crucial to ensure more robust scientific research and clear career paths for EC researchers.

Equality issues of underrepresented groups within the Latin American and Caribbean scientists

Historically, Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) has been traditionally patriarchal and has cultivated a false assumption that men are innately well-suited for scientific research while women are not44. However, many studies have been conducted to disprove this idea and encourage gender equality policies to correct the imbalance between men and women in science45. Despite all these efforts, a considerable challenge for implementing equitable policies is the lack of information on the extent and magnitude of gender imbalance in science in nations with low research and development expenditure46.

According to the Scimago Country Rankings, most of the scientific publications authored by researchers in the LAC region from 1996 to 2020 were produced by five countries – Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Chile, and Colombia, covering 88.26% of all scientific topics and 86.56% of environmental science47. It is important to note that these are total numbers for scientific publications and are not separated by gender. If gender disparity is considered among these five countries, only Argentina and Brazil have achieved gender parity in the number of women employed in research48,49. The ranking suggests that inequalities might be worse in countries where science suffers from a substantial lack of funding50, which might prevent the creation of programs that stimulate the increase of women in science.

In 2019, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) presented data on the number of women employed in research and development. Although the rate of employed women in the LAC region (45.1%) represented relatively good performance in worldwide indexes of gender parity in science, especially when compared to the global rate (29.3%), women researchers in LAC still face many challenges as discrimination, unequal pay and funding disparities when pursuing a career in science46,48,51. In general, the UIS numbers are based on headcounts, the total number of women employed in research and development, and therefore do not differentiate STEM from other sciences with higher women representativeness (e.g., humanities and social sciences51). Additionally, the total numbers lack an explanation for the larger gender disparities in senior levels, the large gap in authorship positions associated with seniority, the fewer women authors in prestigious journals, and the higher number of men to be invited by journals for paper submission52.

Other groups are underrepresented in STEM in LAC institutions. The LGTBIQA+ group is one of them. However, we have not found studies that directly tackled the representativeness of LGTBIQA+ within STEM in LAC. Our searches brought to us blogs and organizations (e.g., the STEM village; https://www.thestemvillage.com) that offer a platform for improving LGTBIQA+ visibility, but it has not been found statistics that could provide a better perspective of this community within LAC scientists. In addition, other groups such as Black people, indigenous, and mestizos face consequences of inequalities within STEM in LAC. The racialized structure of STEM higher education perpetuates enormous disparities resulting from structural racism, which informs and is reinforced by discriminatory beliefs, policies, values, and resource distribution53. In LAC, in countries like Mexico and Brazil, mestizaje, or racial and cultural mixing, were projects advertised as the symbol of the nation and the hope of its future to offer an idea of high tolerance in LAC; however, behind this idea, the mestizaje had a role by encouraging mixing to further whitening, by denying Black and indigenous identities and cultures, and by homogenizing the racial and ethnic distinctions necessary for anti-racist mobilization54. These historical facts have certainly impacted the under representativeness of these groups within STEM in LAC, but the lack of studies prevents us from showing statistics for the whole LAC. This presents an acute symptom of the reality in LAC, in a sense that discussions on the representativeness of Black people, indigenous, and mestizos are still very preliminary within STEM in LAC and that scientific research on this topic is probably concentrated in humanities and social sciences.

Recently, the socio-economic crisis imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the problems faced by underrepresented groups in LAC. Gender, race, parenthood, and intersectionality are essential factors in assessing how the pandemic has affected scientists. Recent studies have shown that women and mothers are the groups taking the strongest hit in academia in the US and Europe, with lower rates of paper submission and publication, as well as fewer grant proposal submissions during the pandemic55,56,57,58. In LAC, we found similar results in a comprehensive study conducted in Brazil that revealed that in STEM, male academics (especially those without children) were the least affected, whereas Black women and mothers were the most impacted scientists49. These impacts are likely a consequence of the exacerbated unequal division of domestic labor during the pandemic, and that racism strongly persists in academia, especially against Black women; in addition, EC scientist women (regardless of race) might have been disproportionately affected since the early career period aligns with the reproductive age of these women58. Young children require much more attention and care, which was exacerbated during the period of social isolation. That can reduce the number of hours dedicated to research and likely to paper submission56,57,58. These recent studies suggest that the pandemic will have long-term effects on the career progression of these already underrepresented groups and that affirmative policies are urgently needed for reparation.

In summary, despite recent progress, the gender disparity in LAC science is likely to persist for generations. Gender imbalance in the LAC region is deeply affected by Latino cultural stereotypes, notably contributing to Latinas leaving academia59. Therefore, the combination of limited funding and poor working conditions promotes a reduction of women in science and can create a collateral brain drain, with Latinas moving to high-income or less-unequal countries to pursue a career in science. The contribution of other underrepresented groups—LGTBIQA+, Black people, indigenous, mestizos—within STEM in LAC and their intersectionality need to be further investigated to offer a deeper view of the current situation. Within the LAECESS network (see next section), we expect to boost discussions on how to increase the number of underrepresented groups in science, especially in Earth system sciences, including discussions on promoting their access to seniority positions within their countries. For the LAECESS network, it is imperative to increase the number of underrepresented groups as diversity is a keystone for building high-quality and innovative science60,61.

[ad_2]

Source link