Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans

[ad_1]

In this issue, we focus on the topic of mistrust of health care providers or systems among Black Americans, who are much more likely than whites to get seriously ill and die from COVID-19 but less willing to take the coronavirus vaccine. To draw lessons on ways of building trust with Black patients, we looked at clinical encounters in which the stakes of not addressing mistrust are high, including childbirth, childhood vaccination, and the care of patients with HIV, cancer, and substance use disorder. Many of the programs we found have focused on improving communication, increasing transparency, creating welcoming environments, and attending to access barriers, among other approaches for engaging patients who have been poorly served by the health care system.

The medical establishment has a long history of mistreating Black Americans — from gruesome experiments on enslaved people to the forced sterilizations of Black women and the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study that withheld treatment from hundreds of Black men for decades to let doctors track the course of the disease. So it’s not surprising that just 42 percent of Black Americans said in November they’d be willing to take a COVID-19 vaccine. As Michael Che, one of the stars of Saturday Night Live, quipped last month, “I’ve got mixed feelings about the vaccine. On the one hand, I’m Black, so naturally I don’t trust it. But on the other hand, I’m on a white TV show, so I might actually get the real one.”

Mistrust of the health care system persists even among some Black medical professionals such as Oni Blackstock, M.D., a primary care physician, researcher, and former assistant commissioner of New York City Health Department’s Bureau of HIV. When Blackstock’s seven-year-old son needed to go the emergency department (ED) for a skin abscess, she hesitated. The last time Blackstock had taken him to the ED — for a broken wrist — a white orthopedist reset the bone without giving him a painkiller. “I have never seen so much fear in my child’s face,” Blackstock recalls, “and I felt completely responsible.” To avoid a similar experience, she phoned her twin sister, an ED physician, who called ahead to ensure that a trusted colleague would treat her nephew.

Studies have found Black Americans are consistently undertreated for pain relative to white patients; one revealed half of medical students and residents held one or more false beliefs about supposed biological differences between Black and white patients, like the former have higher pain tolerance than the latter. In addition to this kind of differential treatment, the health care system often gives short shrift to the physical and emotional tolls of exposure to police brutality; substandard housing and schools; polluted neighborhoods; or other parts of the daily experiences of some Black Americans. Our September 2018 issue of Transforming Care described how health systems are working to reduce health disparities by confronting racism head on. In this issue, we look at the problem of mistrust, which has risen to the fore during the pandemic amid concerns about its effects on Black Americans. As a group, they are much more likely than whites to get seriously ill and die from COVID-19 but less willing to take the coronavirus vaccine.

What Is Medical Mistrust?

A growing body of researchers is exploring the factors that fuel medical mistrust, particularly among Black and other patients of color. Laura Bogart, Ph.D., a social psychologist and senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation whose research has documented the effects of medical mistrust on HIV prevention and treatment outcomes, defines medical mistrust as an absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patients’ interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results.

Bogart and other researchers have found that medical mistrust is not just related to past legacies of mistreatment, but also stems from people’s contemporary experiences of discrimination in health care — from inequities in access to health insurance, health care facilities, and treatments to institutional practices that make it more difficult for Black Americans to obtain care. As she describes in a Q&A below, lack of trust can either be harmful (e.g., by causing people to avoid care) or empowering (e.g., by encouraging people to pursue health system reform and broader social change).

Often, patients who don’t trust their health care providers are labeled as noncompliant and blamed for their failure to benefit from treatment. “Even the term mistrust is victim blaming,” says Kimlin Tam Ashing, Ph.D., director of the Center of Community Alliance for Research and Education at the cancer center City of Hope in Los Angeles County, whose research assesses the biological, psychological, and cultural underpinnings of racial and ethnic disparities in cancer outcomes. “It puts it on the community when in fact the community has been let down by the medical system and by providers who continue to discriminate.”

Improving Patient–Provider Relationships

Strengthening relationships between patients and their health care providers may be a means of building trust as some studies have found that people have more confidence in their providers than “the health care system” or “Big Pharma” writ large.

Treating Patients as the Experts

One such effort is part of the Merck for Mothers initiative, which aims to reduce maternal morality worldwide; in the U.S., Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes then white women. Among the explanations: providers spend less time with Black patients, ignore their symptoms and complaints, and lose contact with them during the postpartum period when women undergo major physiological changes that put them at risk of death.

In 2019, the Merck for Mothers initiative brought together Black women in New Orleans; doulas from Birthmark Doulas; OB-GYNs from Touro LCMC Health, a local community hospital; and other perinatal care professionals for “Equity Action Labs.” During the labs, women described the problems they’d experienced during delivery and with prenatal and postpartum care with local providers and helped design solutions. Their accounts were troubling: one mother described her child’s long-term health problems that resulted from having her concerns discounted, and many said they’d felt judged by providers or had procedures done to them (e.g., having internal fetal monitors inserted) without their permission.

The women offered suggestions to avoid these experiences, which Touro providers have begun to test, including having OB-GYNs and pregnant women take part in a trust-building visit midway during a pregnancy to explore women’s past experiences with the health care system, their goals for childbirth, and their safety concerns. “Our hope is that by having someone take the time to sit with them and ask these questions, women will feel enhanced trust between themselves and their providers,” says Stephanie Visco, manager of Birthmark Doulas, a collective that is working to improve birth outcomes among low-income women.

Touro is also piloting a navigation program to offer women postpartum supports that are more comprehensive and longer than the typical six-week period. In addition, the hospital has begun to offer providers case-based training in structural and institutional racism and mandated implicit-bias training for all providers and staff.

Using Empathy, Not Arguments

In an effort to encourage Black patients to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trials, Pfizer partnered with clinical research sites in minority communities and worked with community organizations to have trusted leaders make appeals. Black representation in Pfizer’s and other clinical trials reached 10 percent, an underrepresentation of the overall population of Blacks in the U.S. (13%). Black medical professionals had some success in recruitment by listening and responding to individuals’ concerns, but public health authorities still face an uphill battle in convincing Black Americans to accept the new vaccines.

Pediatricians who’ve had success persuading skeptical parents to accept vaccinations for their children say effective approaches turn on empathy rather than information. At Kaiser Permanente in Northern California, providers who’ve undergone the health system’s Effective Communication without Confrontation training program are encouraged to understand parents’ challenges (e.g., by acknowledging there’s a lot of information about vaccinations and mixed messaging to sift through) and recognize their shared goal, which is to protect children.

Jessica Jaiswal, Ph.D., assistant professor in the department of health sciences at the University of Alabama, says providers may feel compelled to try to dispel patients’ conspiracy beliefs, but hearing and validating patients’ concerns before offering new information may be a more helpful approach to building trust. “I don’t know if it’s useful to try to convince someone that the government did not create HIV to kill Black people,” Jaiswal says, referring to the theory that the U.S. military deliberately created HIV. “However, I think it’s worthwhile to acknowledge the hundreds of years of institutional racism that make someone think that.”

With COVID-19 vaccines, Kenneth Hempstead, M.D., a pediatrician who serves as vaccine communications lead for Kaiser Permanente in Northern California, says both empathy and information are important; because these are new vaccines, clinicians need to be extraordinarily transparent about what we do and don’t know about long-term safety concerns. “I’m optimistic about the vaccines,” he says. “But if we say we have 100 percent confidence in them, and there turns out to be a problem, we run the risk of ruining the public’s trust in all vaccines.”

Building Relationships Outside Exam Rooms

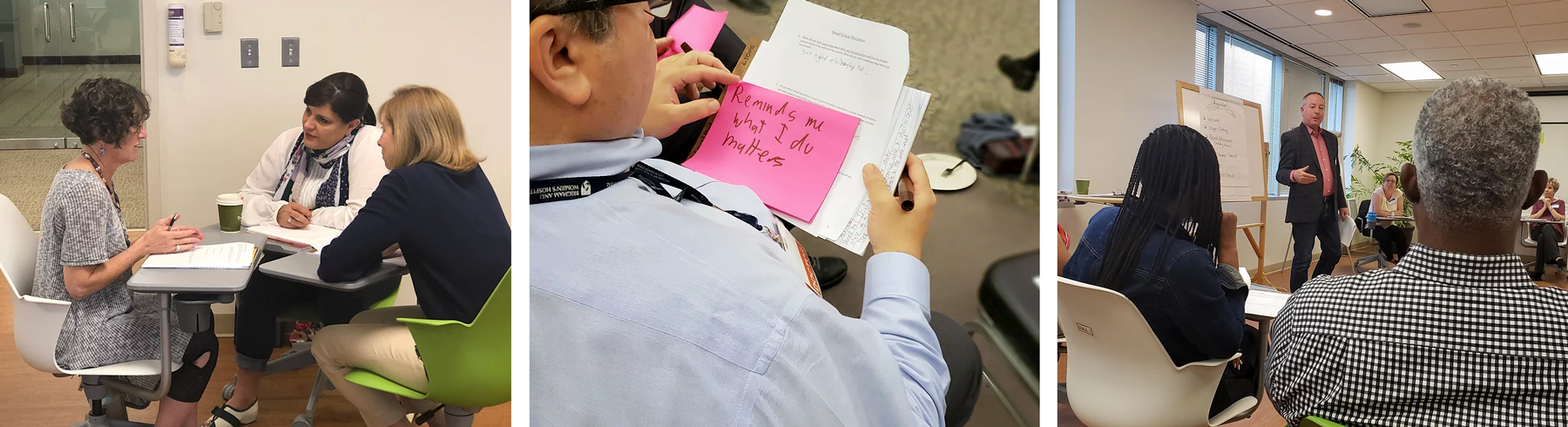

Some advocates say that engendering trust among patients and providers will require carving space outside of the exam room. That’s the idea behind 3rd Conversation, a program led by X4 Health, a social impact design firm, and funded by the Andrew and Corey Morris-Singer Foundation. The program’s designers recognized patients and providers were having separate conversations about their health care experiences and frustrations. 3rd Conversation provides a space where they can come together to share their experiences and strengthen their relationships, with an eye toward finding solutions together.

At 3rd Conversation events, pairs of clinicians and patients get together for facilitated conversations; each is asked to share a personal story about when a relationship with a health care provider or patient made a significant difference to them. The sessions have revealed that clinicians and patients often want similar things, like more time during visits to get to know each other and less time spent looking at screens. Clinicians have also expressed frustration at their inability to help patients with social and economic challenges. “It demoralizes them when a patient comes in and is sick from pneumonia and they can give them medication, but they know the patient is going to sleep in a homeless shelter where they are apt to become sick again,” says Jennifer Sweeney, cofounder of X4 Health.

Sweeney says interest in 3rd Conversation remains high, even amid the pandemic, with requests coming in from large health systems and academic medical centers to private physician practices, and federally qualified health centers.

Making Institutional Changes

Studies that rely on surveys such as the Medical Mistrust Index — which asks respondents how strongly they agree with statements such as “When healthcare organizations make mistakes they usually cover it up,” and “Healthcare organizations are more concerned about making money than taking care of people” — have found that many people distrust the policies or motives of institutions, not the people who work there. Building trust will require coupling efforts to improve interpersonal relationships with broader efforts to change health care institutions, ones that involve clear-eyed examinations of how these institutions have and have not supported the communities they serve.

Uncovering Instances of Institutional Racism

At Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, staff have deliberately sought to uncover instances of institutional racism — that is, differential access to goods, services, or opportunities by race — as part of the work of the Department of Medicine’s Health Equity Committee. The goal is to find concrete examples of how racism affects care within the walls of their institution and use critical race theory and quality improvement methodologies to change the status quo. “After much conversation and debate, the concept of institutional racism was no longer distant, abstract, or someone else’s problem,” says Michelle Morse, M.D., M.P.H., former co-chair of the committee and a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s.

One project grew out of an analysis showing that, from 2008 to 2017, Black and Latino heart failure patients admitted to Brigham and Women’s were significantly more likely to be admitted to the general medical service than the specialty cardiology service. Rates of comorbidities and insurance status didn’t explain the differences. Nationally, heart failure complications are one of the most common reasons people are admitted to hospitals, and several studies (for example, here and here) have shown that patients who receive care from cardiologists have better outcomes than those who don’t receive this specialty support. At Brigham and Women’s, heart failure patients who were admitted to the general medicine floor were more likely to have unplanned hospital readmissions within 30 days. Unlike those discharged from the cardiology service, patients discharged from general medicine aren’t given extra supports, such as home monitoring and check-in calls.

Leaders have taken immediate and longer-term steps to try to reduce this inequity, including surveying physicians to elucidate what influences their decisions about where to admit patients. In preliminary results, providers said they perceived white patients to advocate more often and more vigorously for access to specialty cardiology services, and that this impacted their decision-making — a phenomenon that hasn’t previously been well described in the literature. They’re also trying to improve the quality of heart failure care on the general medicine service, including by offering follow-ups after discharge. “We’ve already seen shifts in practice, we think in large part because of the ripple effects of the discussion that came about after finding this example of institutional racism within our walls,” Morse says. The next step is an effort to give hospitalized Black and Latino patients preferential access to the subspecialty cardiology service to redress this longstanding injustice.

Attending to Affordability, Access Barriers

Some patients say they are treated with less respect by health care providers because of their income, type of insurance coverage, and/or race, and some fear they may have care withheld or may not receive the best-quality care. To try to engage Black, Latino, and other people of color, the cancer center City of Hope is taking several steps to engage patients and dismantle emotional, financial, and other barriers to accessing and engaging in care.

All patients are invited to complete a survey, SupportScreen, which asks if they are experiencing social, emotional, or financial problems that may affect their ability to follow treatment. The automated system then directs social workers, financial services staff, chaplains, and other supportive care medicine staff to offer help.

Leaders are also trying to make it easier for Black patients and others to take part in clinical trials. Nationally, minority patients are less likely to do so due to restrictive inclusion criteria and patient-level factors, ranging from lack of transportation to concern about lost income from missing work and other costs associated with participation. Communities and potential participants also need assurance that therapeutical clinical trials provide the standard of care at a minimum (i.e., treatments known to be effective won’t be withheld, as happened during the Tuskegee study). To make it easier to take part in trials, City of Hope has partnered with community hospitals and built or acquired community practices, some in parts of suburban Southern California that lack oncologists or oncology subspecialty services. In a trial funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and led by City of Hope researcher Ashing, the cancer center is training community ambassadors and research navigators to increase awareness and acceptability of biomedical studies, including clinical trials, among underrepresented populations.

Ultimately, it will be important to encourage more people to receive timely cancer screenings, Ashing says. Nationally, Black people have worse outcomes for many types of cancer, including lung, colon, cervical, breast, and blood cancers, due in part to the fact that they are often diagnosed at later stages.

Creating Safe, Welcoming Environments

While reviewing historical practices, health systems can take immediate steps to make patients who’ve been marginalized feel more welcome. UnityPoint Health system, a network of hospitals, clinics, and home care services in Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, sought to redesign care for its LGBTQ patients after hearing about the challenges Kyle Christiason, M.D., one of UnityPoint Health’s physicians, faced finding appropriate medical options for his son after he identified as transgender.

Together, Christiason and UnityPoint Health created the system’s first LGBTQ clinic in Cedar Falls, Iowa, in 2018. In developing it, Christiason and his colleagues proceeded with an attitude of cultural humility: acknowledging what they didn’t know and getting input from LGBTQ community members by holding town hall meetings and focus groups and fielding surveys. One of the clinic’s first patients told Christiason he hadn’t felt comfortable telling his primary care physician of 20 years that he was gay because he hadn’t wanted to disappoint him. Nationally, many LGBTQ people say they don’t trust their providers enough to divulge information about their gender identity or sexual orientation; more than half say they’ve experienced some type of discrimination in health care, including having providers refuse to treat them.

All of the clinic’s staff take part in regular Safe Zone training on LGBTQ identities and how to serve as allies. Christiason says having consistent routines, like asking people about their pronouns, makes a difference. “If I know your behavior is going to happen this way every time, that starts to create trust,” he says. The clinic, held two evenings each month, provides routine primary care as well as pre-exposure prophylaxis to help prevent HIV transmission, gender-affirming hormone therapy, and postsurgical care following gender-affirming procedures.

Staff end each clinic with a huddle to review what did and didn’t go well, discuss ways to improve, and share examples of what brought them joy in their work. “Sometimes they’re tiny, like ‘I got someone to smile,’” Christiason says. “Sometimes they’re quite profound. Once, someone came out of an exam room and said, ‘I just want you all to know that because you chose to let me be my most authentic self, I decided not to kill myself after my last visit. I’ve been thinking about how I can end my life for 10 years, and now for the first time, I think I can take care of myself because you showed that I matter.’’’

After receiving positive feedback on the first clinic, the health system established a second LGBTQ clinic in Des Moines.

Signaling Commitment to Improving Patients’ Experiences

Geisinger Health System’s Proven Experience program encourages patients who have had a poor experience to apply for no-questions-asked refunds of copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles as a way of building trust. Applicants are told, “You placed your trust in us, and we place our trust in you.”

The idea for the refund, which came from an incoming CEO, initially met with resistance from other health system leaders who worried about financial losses, the legalities of such a program, and the possibility of specious complaints, says Greg Burke, M.D., chief patient experience officer. Burke says these problems haven’t materialized since the program’s inception in 2015; instead, it has helped leaders spotlight and correct problems and sends a signal to patients “that the system wants to hear how we are doing,” he says. Complaints related to perceived lapses in quality or differences of opinion about the course of treatment are excluded from the refund program and are referred to Geisinger’s internal safety division instead.

Most complaints (70%) relate to communication failures, such as providers saying something hurtful or not following up as promised. Geisinger gives all new physicians and advanced practitioners a four-hour training course on effective communication, with a focus on making eye contact, introducing yourself, informing patients of what you are doing and asking permission, being personable, and ending on an upbeat note. Providers who have persistent problems are offered individual coaching sessions.

Involving Patients in Research

Involving patients in research aimed at improving care, known as participatory research, is another mode of building trust. Starting in 2015 at Yale School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry, researchers engaged in a participatory research training exercise with members of the local community who were in recovery from substance use disorder and other behavioral health conditions. One of their goals was to make behavioral health research more responsive to the concerns of community stakeholders, particularly for people of color.

Over the course of two years, people in recovery met with clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and community advocates to explore ways they could work together to conduct participatory research. Participants were given opportunities to share their stories and offer suggestions. One finding was that researchers and patients may have different priorities, with the latter often focused on practical changes that help them achieve their goals rather than on clinical diagnoses or effects, says Miraj Desai, Ph.D., an instructor at Yale’s Program for Recovery and Community Health and the project director. “People overwhelmingly focused on seeing concrete meaningful changes in their communities and lives and wanted to know how research can be more closely aligned with these goals,” he says.

Participants also suggested researchers should create opportunities for trial investigators and community partners to get to know each other, such as by sharing meals; address the challenges patients may face in joining projects (e.g., finding transportation or missing work); and create opportunities to discuss racism, poverty, and other social problems that affect health.

Moving Forward

These and other efforts suggest that some health care professionals and systems had begun taking the problem of medical mistrust seriously well before the need to vaccinate most Americans made it urgent. Some of the work was driven by professional societies, including the American Board of Internal Medicine, which has worked to rebuild trust in the medical profession since 2018, in part by building a compendium of trust-building practices. The Journal of the American Medical Association, Behavioral Medicine, and other journals have also devoted commentaries and/or issues to the subject.

Not all of the initiatives we’ve featured are focused on the particular experiences of Black Americans. To move forward, efforts are needed to document and understand the many reasons fueling medical mistrust of health care providers and institutions among Black patients by documenting the problem and learning from patients about what may help. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement recently launched its second round of the Pursuing Equity Learning and Action Network, in which teams of community health centers, free clinics, and large health systems are examining the impacts of racism within their organizations and communities and deploying improvement strategies to close specific equity gaps.

Changing facts on the ground will be important, including reviewing not just hiring, promotion, and procurement practices at health care organizations but also where they have chosen to locate and upgrade facilities. Including more Black people in clinical and leadership roles will also be necessary but not sufficient. Efforts are needed to expand the health care workforce to include peers and navigators in supporting patients, make the history of racism in medicine a required part of health professionals’ training, and create systems to identify and address instances of disparate care.

Ultimately to earn Black patients’ trust, policy changes are needed to make it easier to access and afford care. When asked if seeing President Obama receive the COVID-19 vaccine on camera would persuade them to get vaccinated, two Black men pointed out to a Washington Post reporter that should the former president experience serious side effects he’d have access to the best doctors and receive care that is unimaginable in their own or other low-income communities.

Q&A: Broaching Conversations About Medical Mistrust

Laura Bogart, Ph.D., is a social psychologist and senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation whose research has documented the effects of medical mistrust on HIV prevention and treatment outcomes. Transforming Care spoke to Bogart about how clinicians and health systems can broach conversations about mistrust and ameliorate its effects.

Transforming Care: You’ve described medical mistrust as a form of resilience and a healthy survival mechanism that arises in response to oppression. How does framing mistrust in positive terms change how we go about addressing it?

Bogart: If we recognize that mistrust isn’t necessarily harmful, it changes how we frame our response. It’s very natural that people would want to put their guard up and ready themselves for the possibility of discrimination after experiencing so much systemic racism. If channeled effectively, mistrust can empower people to protect themselves and pursue changes at the institutional and societal levels. Mistrust becomes problematic when it stops people from engaging in healthy behaviors or when it leads to avoidance of the health care system.

Transforming Care: What advice would you give to providers who are interested in talking about mistrust with their patients?

Bogart: I think it has to start with education to raise provider awareness about the levels of mistrust in communities, the origins of it, and its impact on engagement, adherence, and treatment outcomes. In the case of HIV, in a national survey of Black Americans in 2016, we found that a high percentage of Black Americans believe that the virus is manmade (31%), that a cure is being withheld (40%), and that antiretroviral treatment is poison (33%). We also know medical mistrust is correlated with not adhering to medical advice, filling prescriptions, and delaying cancer screenings and other preventive health measures. It’s also higher among patients who have experienced discrimination.

Transforming Care: What are some of the signs of it in an exam room?

Bogart: It could be a lack of engagement during the health care interaction. A patient may not ask questions. They may not make eye contact or may seem uncomfortable. Some patients won’t verbally agree with providers. They may just take the prescription and leave. These behaviors can be indicative of mistrust. Some patients may be more direct and say they don’t like medication or don’t trust the medication.

Transforming Care: What sort of techniques do you suggest providers use to broach a conversation about mistrust?

Bogart: There are lot of different techniques and strategies. First and foremost, it’s important to validate mistrust by acknowledging and affirming experiences of discrimination and conveying that patients’ thoughts, behaviors, and emotions are well grounded, justifiable, relevant, and meaningful. Their mistrust may stem from recent negative experiences or be a response to historical injustices including unethical experimentation in health care. When exploring mistrust, it’s important to ask open-ended questions in a nonconfrontational, nonjudgmental way while also providing accurate information. A provider might say, “It’s totally understandable that you might be apprehensive about getting vaccinated given what’s happened in the past and even now with inequality and mistreatment in health care. What have you heard about the vaccine?” A provider could then offer further information if needed by saying, “It sounds like you have been hearing a variety of things. Would it be okay if I told you a little about what I know about the vaccine?”

Transforming Care: You created the HIV Conspiracy Belief Scale to assess the prevalence of beliefs that HIV is manmade and a cure is being withheld. What have you learned about what drives conspiracy beliefs?

Bogart: I define the term conspiracy more neutrally than others do — as an effort to explain the cause of an event, practice, or circumstance by referencing the actions of powerful people who attempt to conceal their role. They may be true or untrue. It’s important to avoid putting a value judgment on them. They can serve several psychological needs by helping to explain why one group isn’t doing as well as another. They can also provide a sense of control and security for people who are feeling threatened or powerless, such as in the face of discrimination, or have an expectation of future mistreatment.

Transforming Care: You’ve also distinguished mistrust that is based on suspicion of malicious intent, such as genocidal beliefs, and mistrust based on concern about benign neglect — more of a carelessness or indifference that may lead to bad things happening. Are there differences in the characteristics of people who hold one view or the other?

Bogart: In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, we have found that people with lower levels of education and income may be more likely to have mistrust-related beliefs, but these are not strong effects, and we don’t find either education or income accounts for a lot of the variance in how much people hold these beliefs. There may be a social norm around medical mistrust, which means that it may be acceptable and common in communities, families, and social networks, to have such beliefs — which is why it is important to tackle mistrust at the community level.

Transforming Care: What are some strategies health care organizations can use to address mistrust within the communities they serve?

Bogart: It requires genuine partnership. There are a lot of organizations — churches and community groups among them — that can help elucidate reasons for mistrust, where the mistrust is coming from, and what specific kinds of mistrust-related beliefs are common in communities. The key is that health care organizations need to act on the feedback they receive and not just pay lip service to it.

Transforming Care: What about when it comes to providers having conversations with patients? Some providers may have less empathy or difficulty restraining their desire to correct the patient, what you call the “righting” reflex? Do you think everyone can be trained to be responsive to patients’ concerns?

Bogart: I do think people can be trained on very basic skills. Some people are going to take it further than others. Some people are going to be better at it. But as for the basic skills—providers can learn them. People who do try actually may find that it’s gratifying, because it doesn’t take that much or any more time, but you see better adherence among patients and better patient satisfaction and outcomes.

Publications of Note

Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas Led to Delayed Care, Medical Debt

Arkansas was the first state in the nation to impose work requirements to qualify for Medicaid coverage, compelling most adults between the ages of 30 to 49 to work 20 hours a week or participate in “community engagement” activities. Before a federal judge put the policy on hold in April 2019, 18,000 adults had lost coverage. A survey of low-income adults in the state found more than half of those who lost access to Medicaid after the work requirements were imposed delayed care (56%) and/or postponed taking medication (64%) because of concerns about costs, while half reported serious problems paying off medical debt. These rates were significantly higher than those among Arkansans who did not lose Medicaid coverage. The survey also found that the work requirement did not increase employment over 18 months and that awareness of the policy remained poor, with more than 70 percent of Arkansans reporting they were unsure whether the policy was in effect. Most of the coverage losses were reversed after the court order. Benjamin D. Sommers et al., “Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Two-Year Impacts on Coverage, Employment, and Affordability of Care,” Health Affairs 39, no. 9 (Sept. 2020):1522–30.

Access to Midwifery and Birth Centers Under Medicaid

Interviews and focus groups with Medicaid officials and staff at birth centers in states that participated in the Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns II initiative — an effort to test different models of prenatal care for Medicaid beneficiaries, including comprehensive team-based care at birth centers — revealed that Medicaid beneficiaries chose birth centers because they preferred midwifery care, wanted a natural childbirth, or wanted other services that may be not available in hospitals. However, the key informants also said that beneficiaries have less access to birth centers than do privately insured patients because of lower Medicaid reimbursement rates, as well as the challenges of contracting with managed care organizations and participating in value-based delivery system reforms. The authors say addressing these barriers could improve birth outcomes for mothers and newborns while yielding savings for Medicaid programs. Brigette Courtot et al., “Midwifery and Birth Centers Under State Medicaid Programs: Current Limits to Beneficiary Access to a High‐Value Model of Care,” Milbank Quarterly September 15, 2020.

Indiana’s Medicaid Waiver and Interagency Coordination Increased Enrollment for Justice-Involved Adults

After Indiana’s 2015 Medicaid waiver expanded eligibility for low-income adults, the state sought to increase the number of justice-involved adults covered by the program by increasing coordination between the state’s corrections agency and its Medicaid program. As part of the effort, the Indiana Department of Correction began initiating Medicaid applications for inmates who lacked coverage and suspended rather than discontinued coverage for others while they were incarcerated. The Medicaid expansion increased the percentage of justice-involved adults who received Medicaid coverage within 120 days of release by nine percentage points. With coordination between agencies, the state saw an additional 29-percentage-point increase in coverage. The study also found a 14-percentage-point increase in the number of inmates who had coverage that was effective within seven days of their release. Justin Blackburn et al., “Indiana’s Section 1115 Medicaid Waiver and Interagency Coordination Improve Enrollment for Justice-Involved Adults,” Health Affairs 39, no. 11 (Nov. 2020):1891–99.

Early in the Pandemic Older Adults with Low Health Literacy Were Unable to Accurately Identify Ways to Prevent COVID-19 Infection

Researchers found older adults at higher risk for COVID-19 lacked critical knowledge about prevention in the early weeks of the pandemic. The surveys of adults with one or more chronic conditions, conducted at the outset of the U.S. outbreak (March 13–20, 2020) and during the acceleration phase (March 27–April 7, 2020), found that while participants increasingly perceived COVID-19 to be a serious public health threat and reported more changes to their routines, there was no significant change in the proportion who could accurately identify ways to prevent infection. Black adults and those with lower health literacy were more likely than whites and those with higher health literacy to report feeling less susceptible to becoming sick with COVID-19. In addition, individuals with low health literacy remained more likely to feel unprepared for the outbreak and to express confidence in the federal government response. The authors conclude that public health messaging to date may not be effectively reaching vulnerable communities. Stacy Cooper Bailey et al., “Changes in COVID-19 Knowledge, Beliefs, Behaviors, and Preparedness Among High-Risk Adults from the Onset to the Acceleration Phase of the US Outbreak,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 35, no. 11 (Nov. 2020):3285–92.

Reproductive Health Issues May Foreshadow Cardiovascular Disease in Later Life

A review of studies that have investigated the association between reproductive risk factors in women and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease found a variety of risk factors — from early menarche and contraceptive use to gestational diabetes and preterm birth — were associated with cardiovascular disease. The researchers found associations for composite cardiovascular disease were twofold for pre-eclampsia, stillbirth, and preterm birth; 1.5- to 1.9-fold for gestational hypertension, placental abruption, gestational diabetes, and premature ovarian insufficiency; and less than 1.5-fold for early menarche, polycystic ovary syndrome, and early menopause. The associations varied for ischemic heart disease, stroke outcomes, and heart failure. A longer length of breastfeeding was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. The authors say policymakers should consider incorporating reproductive risk factors into clinical guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment since the risk of cardiovascular disease may be modifiable. Kelvin Okoth et al., “Association Between the Reproductive Health of Young Women and Cardiovascular Disease in Later Life: Umbrella Review,” BMJ 371, no. 8263 (Oct. 2020):m3502.

Declines in Non-COVID-19 Hospital Admissions Vary by Diagnosis, Patient Population

Researchers studying differences in hospital admission patterns among patient groups since the onset of the pandemic found that declines in non-COVID-19 admissions between February and April 2020 were generally similar across demographic subgroups and exceeded 20 percent among all primary admission diagnoses. By late June and early July 2020, non-COVID-19 admissions were 16 percent below pre-pandemic levels, but admissions were substantially lower for patients residing in majority-Latino neighborhoods (32% below baseline) and remained well below baseline for patients with pneumonia (down 44%), COPD and asthma (down 40%), sepsis (down 25%), urinary tract infection (down 24%), and acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (down 22%). John D. Birkmeyer et al., “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hospital Admissions in The United States,” Health Affairs 39, no. 11 (Nov. 2020):2010–17.

Complex Patient Bonus Unlikely to Mitigate Regressive Effects of MIPS

A review of the first round of performance data from the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) found that compared with clinicians with the lowest socially at-risk caseloads, those with the highest had 13.4 points lower performance scores, were 99 percent more likely to receive a negative payment adjustment, and were 52 percent less likely to receive an exceptional performance bonus payment. The authors note the lower scores were partly explained by lower clinician reporting of and performance on technology-dependent measures, which may reflect lack of technological capability at the practice level. They also found that having a complex patient bonus in place would have increased performance scores and the likelihood of receiving an exceptional performance bonus for clinicians with the highest socially at-risk caseloads by 4.7 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively. However, the proportion receiving negative payment adjustments would have remained unchanged. The study included data on more than 500,000 clinicians. Kenton J. Johnston et al., “Clinicians with High Socially At-Risk Caseloads Received Reduced Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Scores,” Health Affairs 39, no. 9 (Sept. 2020):1504–12.

Policy Changes to Improve Pandemic Response, Increase Health Equity

In a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine, three health disparities researchers call for major policy changes to advance health equity and improve the pandemic response, including greater investment in hospitals and clinics that serve marginalized communities, the creation of a universal food income benefit, and reforms to unemployment insurance to increase income and broaden eligibility. They also recommend greater investment in community development, expanding affordable housing, and increasing economic opportunity to reduce income disparities. Seth A. Berkowitz, Crystal Wiley Cené, and Avik Chatterjee, “COVID-19 and Health Equity — Time to Think Big,” New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 12 (September 2020):e76.

Employment May Explain Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Minorities

Blacks and Latinos are more than three times as likely as whites to be hospitalized with COVID-19 and experience higher death rates from the disease. Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, researchers found these disparities are not fully explained by health risks, such as diabetes or obesity. They found Blacks were substantially more likely than whites to work in health, public safety, and public utility jobs while Latinos were more likely than whites to work in food-related jobs, suggesting employment may be a factor in transmission within households. Blacks at high risk for severe COVID-19 illness were 1.6 times as likely as whites to live in households with health-sector workers. Among Latino adults at high risk for severe illness, 64.5 percent lived in households with at least one worker who was unable to work from home versus 56.5 percent among Black adults and 46.6 percent among white adults. Thomas M. Selden and Terceira A. Berdahl, “COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health Risk, Employment, and Household Composition,” Health Affairs 39, no. 9 (Sept. 2020):1624–32.

Geography, Employment, Incarceration, and Other Factors May Explain Differences in COVID-19 Cases Among Minority Groups

Reviewing data from 351 cities and towns in Massachusetts, researchers found communities with a higher proportion of Black and Latino residents had higher rates of COVID-19 cases. A 10-percentage point increase in the Black population was associated with an increase of 312.3 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents, whereas a 10-percentage point increase in the Latino population was associated with an increase of 258.2 cases per 100,000 residents. For the Latino population, independent predictors of higher COVID-19 rates included the proportion of foreign-born noncitizens living in a community, mean household size, and share of workers employed in the food service sector. Higher COVID-19 cases among Blacks were not explained by these and other demographic, economic, and occupational variables studied. The researchers suggest higher COVID-19 cases among Blacks may be explained by other factors, including disproportionate incarceration rates, residence in multi-unit buildings, and segregation, which may produce variation in access to care and exposure to environmental hazards. Jose F. Figueroa et al., “Community-Level Factors Associated with Racial and Ethnic Disparities In COVID-19 Rates in Massachusetts,” Health Affairs 39, no. 11 (Nov. 2020):1984–92.

Mental Health Disorders Linked to Grief May Increase with More COVID-19 Deaths

In a commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association, three psychiatrists call for greater investment in mental health funding to address the psychological problems experienced by Americans who have lost loved ones to COVID-19, including grief, depression, and substance abuse. They also call for widespread screening to identify individuals at highest risk for prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress, and suicide and recommend training for primary care clinicians and mental health providers conducting screening and offering support to the bereaved who cannot participate in traditional mourning practices. Naomi M. Simon, Glenn N. Saxe, and Charles R. Marmar, “Mental Health Disorders Related to COVID-19–Related Deaths,” Journal of the American Medical Association 324, no. 15 (Oct. 2020):1493–4.

Minnesota’s Payment Policy for Medicaid Births

In 2009, Minnesota’s Medicaid agency established a single payment rate for uncomplicated vaginal and cesarean births, a change from the prior payment that had given providers higher reimbursements for cesarean births. Researchers seeking to determine if the policy had differential effects on cesarean birth rates and maternal morbidity among Black and white women in Minnesota, as compared to six other states, found cesareans decreased among both Black and white women in Minnesota compared to the control states and this decline was greater among Black women (a decline of 2.88 percent from a pre-policy rate of 22.2 percent) than among white women (a decline of 1.32 percent from a pre-policy rate of 19.3 percent). Rates of postpartum hemorrhages increased, with larger increases among Black women. Jonathan M. Snowden et al., “Cesarean Birth and Maternal Morbidity Among Black Women and White Women After Implementation of a Blended Payment Policy,” Health Services Research 55, no. 5 (October 2020):729–40.

Editorial Advisory Board

Special thanks to Editorial Advisory Board member Don Goldmann for his help with this issue.

Jean Accius, Ph.D., senior vice president, AARP

Anne-Marie J. Audet, M.D., M.Sc., senior medical officer, The Quality Institute, United Hospital Fund

Eric Coleman, M.D., M.P.H., professor of medicine, University of Colorado

Marshall Chin, M.D., M.P.H., professor of healthcare ethics, University of Chicago

Timothy Ferris, M.D., M.P.H., CEO of Massachusetts General Physician Organization and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

Don Goldmann, M.D., chief medical and scientific officer, Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Laura Gottlieb, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of family and community medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Carole Roan Gresenz, Ph.D., senior economist, RAND Corp.

Allison Hamblin, M.S.P.H., vice president for strategic planning, Center for Health Care Strategies

Thomas Hartman, vice president, IPRO

Clemens Hong, M.D., M.P.H., medical director of community health improvement, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services

Kathleen Nolan, M.P.H., regional vice president, Health Management Associates

J. Nwando Olayiwola, M.D., M.P.H., chair and professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine at The Ohio State University

Harold Pincus, M.D., professor of psychiatry, Columbia University

Chris Queram, M.A., president and CEO, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality

Sara Rosenbaum, J.D., professor of health policy, George Washington University

Michael Rothman, Dr.P.H., executive director, Center for Care Innovations

Mark A. Zezza, Ph.D., director of policy and research, New York State Health Foundation

[ad_2]

Source link