Uterine fibroids often plague Black women. They want less invasive treatments : Shots

[ad_1]

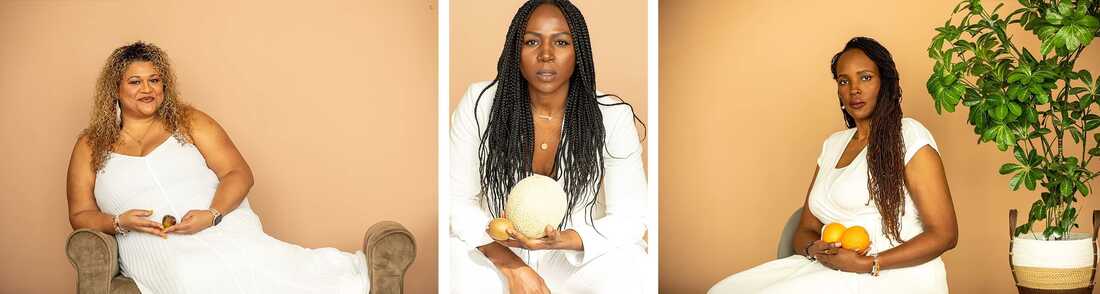

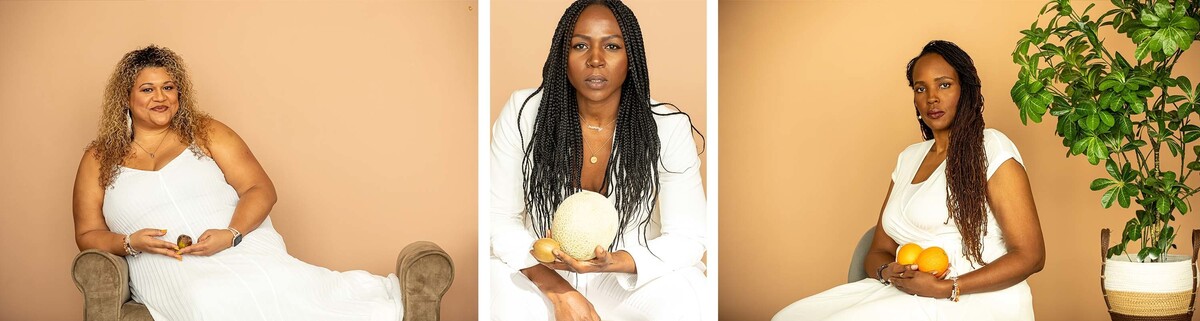

From left, Nichole ‘Nykke’ Straws, Abibat Durosimi and Marsha (last name withheld) hold fruit that is the size of their fibroids. The portraits were made for Hidden Fruit, an educational campaign launched by The White Dress Project and GladRags to highlight the experience of Black women dealing with fibroids.

Kristina Omari was 42 years old when her OB-GYN, a Black woman as well, recommended she get a hysterectomy.

Omari had dutifully attended her check-ups every year, but this was the first time the doctor had ever mentioned the presence of fibroids — noncancerous tumors growing on the wall of her uterus.

She was floored by the idea of such a drastic surgery.

“I was just surprised that through that process of going in for my annual physicals, I wasn’t given more education: ‘Your fibroids are located here. You may not experience symptoms, but they are growing,'” says Omari.

Instead, after the shock of hearing she might have to lose her uterus, she learned a lot more about her condition by talking to friends. Several of them had also been diagnosed with fibroids, which are a common problem, particularly among Black women. They’re at higher risk of the condition and more likely to develop it at younger ages.

Many women with fibroids never notice anything amiss, but approximately 25% to 50% struggle with heavy menstrual bleeding, frequent urination, and pain, which can lead to depression, reproductive health issues, and lower work productivity. Omari’s friends explained that there are an array of possible treatments, including medications and myomectomy, a surgery that removes fibroids and preserves the uterus.

When Omari went back to her OB-GYN to bring up these alternative strategies, the doctor replied, “I would just definitely, you know, at your age recommend [a] hysterectomy.”

Advice like this helps explain why Black women are at least twice as likely as white women to remove their uterus through a hysterectomy. When symptoms are severe, fibroids are the leading reason for hysterectomy in the United States.

Research still cannot pinpoint why Black women are more susceptible to fibroids, but patients like Omari are questioning why they’re being steered so quickly to one kind of treatment when less invasive options are available. It’s the start of a grassroots movement to advocate for a different, more compassionate approach to fibroids, one that encourages the sharing of information and pushes to preserve fertility.

Dr. Octavia Cannon, past president of the American College of Osteopathic OBGYNs, specializes in treating uterine fibroids with support for those who do not want to undergo a hysterectomy. “Some people want to keep the parts that God gave them,” she says.

That was the case for Omari. Luckily, thanks to her friends, she had an alternate view from her doctor’s recommendation. A friend referred her to a “very respectful, thoughtful” surgeon who specialized in minimally invasive treatments. After explaining Omari’s options for preserving her fertility, the surgeon removed her fibroids with “no complications.”

Early detection, individualized care

Patients often come in to Cannon’s practice complaining about heavy bleeding and painful cramping.

“They sometimes say they feel this mass in their belly,” she explains. “They’ve been working out and trying to get their abdomen to be flatter, but they can’t seem to make it, and they don’t know why.”

Many have already seen doctors who recommended a hysterectomy but didn’t offer much education about the condition. So although less than 1% of uterine fibroids are cancerous, patients may worry about the word “tumor.”

“All the doctor has to say is that you have tumors, and immediately, if you don’t know, you’re going to think it’s cancer,” Cannon says. That misunderstanding makes women more likely to agree to a hysterectomy, whether they’ve had children or not, she adds.

Cannon pays close attention to each patient’s appearance and asks lots of questions to get a detailed medical history. That approach is critical, Cannon notes, because early detection of fibroids makes non-surgical treatment more feasible. Clinicians base recommendations on the number, size, type, and location of the fibroids, in addition to the severity of symptoms and the patients’ fertility intentions.

While a hysterectomy may be the proper treatment for certain patients, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved a new medication to treat heavy bleeding related to fibroids, and there are other advances in the field making it possible to shrink the growths.

“There’s so much that can be done now to help women who have fibroids keep their uterus,” Cannon says.

The medical profession can be slow to evolve, says Dr. Erica Marsh, whose work at the University of Michigan focuses on uterine fibroids and disparities in reproductive health care. She’s found that hysterectomies have been historically overused for all women, and especially those of African descent.

There’s a tendency among doctors to become comfortable with a familiar treatment, and then fall back on that, rather than consider what makes the most sense given the circumstances, she says.

“Every patient has their unique set of symptoms and they have to be approached as an individual case,” she says. “Every patient’s goals are unique, their hopes are unique, their fears are unique.”

Marsh hopes that doctors learn to listen more and take advantage of developments that broaden options, but she notes that change will be difficult without a concerted effort. “I don’t know of any specific requirement or specific programming that focuses on education about fibroids in women of African descent,” she says.

It’s hard to quantify how many women have been rushed into unnecessarily extreme surgeries, but Cannon suspects the number is quite high. “I am willing to bet that there are hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions of women who have had hysterectomies, who are women of color, who had a doctor who didn’t care and just took their uterus out before they even could blink,” Cannon says.

Tanika Grey Valbrun photographed on November 13, 2021. Valbrun founded The White Dress Project, a nonprofit organization focused on education, advocacy and support for women with uterine fibroids after her own medical struggle.

A Vizionary Productions

hide caption

toggle caption

A Vizionary Productions

Tanika Grey Valbrun photographed on November 13, 2021. Valbrun founded The White Dress Project, a nonprofit organization focused on education, advocacy and support for women with uterine fibroids after her own medical struggle.

A Vizionary Productions

Raising awareness and starting conversations

The impacts of these decisions shape the path of women’s lives, says Cannon. She recalls crying alongside a Black patient who had felt she had no choice when a doctor surgically removed her uterus decades earlier. “She was 67 [and] still weeping about the fact that she had had no children and she had never had a husband because she felt that she wasn’t a whole woman,” she says.

Open conversations about fibroids and treatment options need to be happening not only in the doctors’ office but also in patients’ homes, Cannon says. She wishes more women were aware of their family history and understood that heavy bleeding isn’t normal.

Some grassroots organizations led by Black women are stepping in to raise awareness. The White Dress Project advocates for women with fibroids and works to destigmatize the condition by providing educational and networking resources. Journalist Tanika Valbrun founded the nonprofit in 2015 after undergoing two myomectomies to remove 27 fibroids.

When she was 14 years old, Valbrun began experiencing heavy bleeding, “I could have had these tumors developing very early and I just didn’t know. And the crazy thing is my mom had fibroids.” Her grandmother did too. Still, they thought Valbrun was too young to have fibroids.

“We need our mothers, our grandmother to talk about this,” she says. “Generational storytelling is so important.”.

By sharing their experiences and proactively seeking treatment, Valbrun says, women with fibroids will be more likely to get the treatment they need. She hopes they won’t be afraid to wear “the white dress” — the kind of clothing she had to give up because of her symptoms.

Speaking out also encourages much-needed funding for medical research and public education, adds Valbrun. She is optimistic that Congress will take action soon on the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021, which would create new programs to disseminate information and collect data, as well as direct substantial additional resources to the National Institutes of Health.

“I absolutely feel the tide changing, where women understand that there are too many of us suffering and too many of us trying to manage life with uterine fibroids,” she says.

Women’s health advocate Tanya Leake, photographed at her home on March 1, 2022. Leake founded numerous initiatives to help raise awareness about uterine fibroids after experiencing them herself.

Alyssa Pointer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alyssa Pointer for NPR

Women’s health advocate Tanya Leake, photographed at her home on March 1, 2022. Leake founded numerous initiatives to help raise awareness about uterine fibroids after experiencing them herself.

Alyssa Pointer for NPR

The chorus of voices continues to expand as Black women connect online about their experiences.

Certified health coach Tanya Leake, 51, traces the beginning of her fibroid journey to 2012, when one of her previously small fibroids started to grow, causing her stomach to visibly protrude and, according to her doctor, pose a risk to her health. She first went the holistic route, and had some success shrinking her fibroid by cutting out alcohol and consuming more vegetables. But it wasn’t enough.

That’s when she began researching medical specialists around Atlanta, looking for a doctor who would listen to her worries and hopes around preserving her uterus. A series of appointments with four different providers only led to disappointment – they all advised her to get a hysterectomy and one doctor never followed up after receiving her MRI results.

It was only after getting recommendations from friends that she found “the one,” a doctor who was skilled in less invasive forms of surgery, and gave her a myomectomy.

“If I hadn’t talked to that friend, I wouldn’t have found my doctor,” says Leake, who detailed the four-year-long saga in a blog post on her website, EmBODY Well.

Commenters chimed in with questions about their fibroids, and Leake learned that many women had similar stories to tell, often involving doctors pushing hysterectomies.

“It just seemed like they came out of the woodwork,” she says.

In response, she created “Coochie Conversations” in 2019, virtual gatherings of about 20 women discussing the challenges around seeking treatment for a variety of women’s health issues, including uterine fibroids. Leake is now turning Coochie Conversations into a podcast.

Rozelle Watson, 72, like many participants, found Leake through her online presence and social network after experiencing pain in her pelvic area. Watson’s gynecologist diagnosed her with a calcified one-centimeter fibroid last year. At the outset of her treatment, she worried about doctors viewing her body “as a car.”

“I don’t want the first thing, the first piece of conversation, [to be] removal — even if it has to be removal,” she says. Watson was relieved that her doctor listened to her concerns and prescribed physical therapy, which cleared up the problem.

Seeking a doctor who honors their wishes

Demystifying fibroids and the available treatment options can also encourage women to seek out the care they need, says Alex Angrand-Robinson, 38. She had never learned much about the condition when she noticed her periods getting markedly longer right after college. So, when her doctor diagnosed fibroids and suggested a myomectomy, she obliged. Three years later, the fibroids returned, worse than before.

She worried about the possibility of another surgery, and couldn’t get clear answers from doctors, who offered a jumble of confusing advice. One recommended hormonal birth control pills that caused severe abdominal cramps.

Diet adjustments helped keep her condition under control for a while. But then, Angrand-Robinson says, “Things went completely downhill.” She became anemic and was easily winded simply walking to work in New York City. One day, she boarded the commuter rail from Connecticut and sat down.

“I didn’t know I was bleeding. All of a sudden, I felt a gush passing through me,” she says. “My entire bottom half was all blood. I thank God, to this day, that I was wearing black.”

After she cleaned herself up at work, showered at the gym, and bought new clothes, she decided she couldn’t go through that again. “I reached a point where I was like, I cannot keep living like this anymore,” she says.

Angrand-Robinson sought out a doctor who would not just perform surgery, but would also listen to her: “I was like, listen, I need two things. Okay, number one, preserve my uterus. Because you know, I want the option of having kids. Number two, I need you to give me a bikini cut. I’m trying to wear my two pieces.” To her surprise, it was no problem to honor both wishes with a second myomectomy.

Alexandra Angrand-Robinson never wore white prior to her 2014 surgery to remove her fibroids. She was thrilled to be able to wear a white dress to her wedding in 2020.

Tunji Studio

hide caption

toggle caption

Tunji Studio

Alexandra Angrand-Robinson never wore white prior to her 2014 surgery to remove her fibroids. She was thrilled to be able to wear a white dress to her wedding in 2020.

Tunji Studio

She calls her 2014 surgery “the best decision I ever made.” And for her wedding in 2020, she was thrilled to be wearing a white dress, “I wear white all the time. That is part of my testimony, I was never able to wear white before now,” Angrand-Robinson says.

This kind of happy ending is what Valbrun hopes for more Black women struggling with fibroids, but it won’t happen if they remain silent about their condition. “It’s time for us to speak out and speak up and use our voice to ignite change,” she says.

Akilah Wise (@awisephd) is a public health researcher and journalist who covers topics in reproductive health.

[ad_2]

Source link