With farm bill, HBCUs see chance to fix historic underfunding

[ad_1]

The country’s 19 historically Black land-grant universities see the upcoming update to the farm bill as an opportunity to make up for historical underfunding and invest in moving these institutions forward, advocates, administrators and experts say.

The farm bill, last updated in 2018, is a wide-ranging package of legislation that authorizes programs and spending related to agriculture and nutrition, including millions for agriculture research and extension services for land-grant universities. The 2018 bill included a number of wins for the Black land-grants such as creating six new centers of excellence and $80 million in scholarship funds for HBCU students. Advocates are hoping to build on those gains in this next update.

“People look at the farm bill as just another piece of agriculture policy, but really, it is one of the driving forces that provides key research, teaching and extension funding to the land-grant universities,” said Denise Smith, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

Those steps were modest, and not enough to make up for historic gaps, wrote Smith in a recent report about the underfunding of the Black land-grants, known as the 1890 universities because of the year Congress established them, compared to predominantly white land-grant universities in their states.

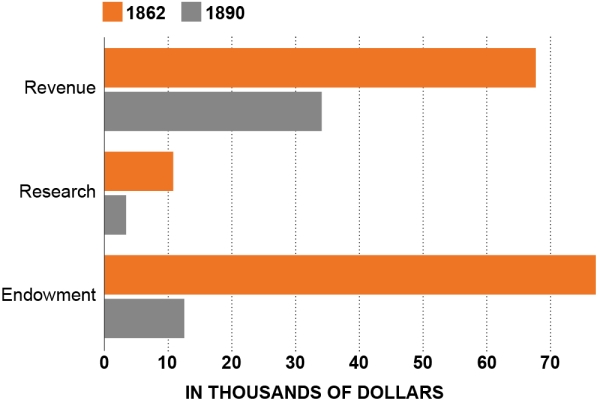

Smith said that “there’s a vast difference in wealth and access between the institution types” despite the fact they were founded not that many years apart. The traditionally white land-grants were first established in 1862. There are now 57 1862 universities and 36 tribal land-grant colleges and universities. A recent Center for American Progress report also documented the disparities among the three institution types.

Comparing Per-Student Revenue, Research and Endowment Resources

Century Foundation, Inside Higher Ed analysis

Smith recommended that Congress provide $600 million in new mandatory funding over the next five years to make up for a combination of federal underfunding and the failure of states to provide matching funds that shortchanged the Black land-grant universities. She also wants Congress to use the farm bill to better support this group of institutions with new investments and policy changes.

“It is important to invest in them, because we’ve continued to have this narrative that these institutions do more with less, and it’s high time that they don’t do more with less,” she said. “This is for the betterment of not only just the institutions, but for the nation.”

Republicans on the House agriculture committee have said they want to unveil a draft of the farm bill next month. Programs authorized in the bill start to expire at the end of September. Congress could pass an extension of the bill through the end of the year to give lawmakers more time to pass an updated bill. Lawmakers have said they don’t expect to have new money for the farm bill reauthorization, given Congress’s fiscal constraints.

Mortimer Neufville, president of the 1890 Universities Foundation, a nonprofit focused on supporting its namesake institutions, said the farm bill is critical to the HBCUs because they’re serving underserved populations.

“We are caught in the crosshairs of doing highly scientific work and doing applied work to meet the needs of the audiences that we’re trying to serve—rural communities and underserved communities,” he said.

He’d like to see Congress expand the number of centers of excellence at HBCU land-grants. The centers started slow because they weren’t fully funded until 2021.

“We are already seeing the impact of some of the centers in terms of student success and workforce development,” he said. “We are able to assist [the U.S. Department of Agriculture] in addressing some of the workforce needs. We’re looking at nutrition and health and how some of our vulnerable populations are. We are trying to meet their needs. So we got a late start, but they are making a definite impact.”

The 1890 Foundation and the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities want Congress to provide funding to upgrade institutions’ research facilities. APLU has requested $5 billion in new money over the next five years. Public agriculture schools and colleges have outdated facilities and are facing $11.5 billion in deferred maintenance costs.

“Many of our facilities, really, are so old, it has to be new construction, not just renovation,” Neufville said.

Heidi Anderson, president of the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, said that infrastructure money is critical. Improving or rebuilding the university’s research facilities would cost at least $100 million, Anderson said. The current labs are outdated and don’t work for students and faculty.

“It would allow us to build some new things and also bring in some more state-of-the-art equipment,” she said of the new money. “If you’re going to teach the students how to go out there and teach the farmers how to do better precision agriculture to grow crops better, they need the equipment to do it.”

The farm bill sets a ceiling in terms of what Congress can spend, and then lawmakers dole out the actual dollars during the annual appropriations process.

Technically, the 1890 group should receive at least 30 percent of what the 1862 group receives for research and 20 percent of the extension funding, but the report found that Congress didn’t always follow that rule. In fact, only in the most recent federal budget did the funding levels follow the law, according to the Century Foundation report.

Black land-grant universities were shorted $436 million over 15 years, the report said.

“While 1862 universities received substantial resources to grow their academic programs, invest in impressive research facilities, and extend services beyond their campus walls to local communities, 1890 universities continued to face deep disparities in federal support,” Smith wrote.

Smith suggested that Congress double the ratios. The APLU has suggested raising the research and extension benchmarks to 40 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

Even when the federal government gives Black land-grant universities money for research and extension services, states have to match that money dollar for dollar, or the universities could forfeit the money.

Neufville said that the required match has been the ceiling rather than the floor for the 1890 institutions, while the 1862 group is funded at higher ratios.

“The USDA requires a 1:1 match as the floor at least, but in many cases, we are trying to reach that 1:1 match,” he said.

Federal law allows states to opt out of the requirement for the 1890 group and only kick in half in matching funds. That’s how this group lost out on $200 million in state funding from 2011 to 2022, according to the Century Foundation report. Universities also have to request a waiver from the federal government to avoid losing the research and extension dollars when the states fail to meet their obligation.

“For those institutions that do not receive their full state match, the consequences are significant in terms of loss of needed resources to invest in research and extension services that benefit rural farmers and communities,” the report says.

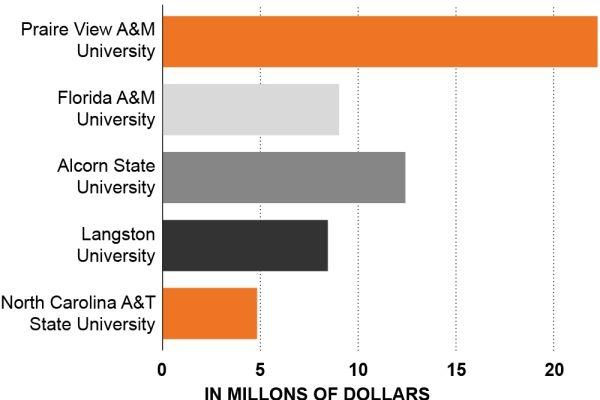

State Matching Shortfalls at 1890 Universities from 2018–21

Maryland Eastern Shore has missed out on $1.76 million in state matching funds from fiscal years 2018 to 2021, according to the Century Foundation report.

In 2021, Maryland agreed to a $577 million settlement in a federal lawsuit that accused the state of underfunding all of the state’s HBCUs and developing competing programs at predominantly white institutions.

Anderson said her university was able to secure the 1:1 match this year.

“We want it to be permanent going forward, so we don’t have to go and ask every single year and that makes a difference,” she said.

More states have started to provide the full match for the Black land-grants in recent years, which Smith chalks up to greater scrutiny of the issue, including lawsuits. In fiscal year 2021, the 1890 universities lost $22 million in state matching funds.

The report recommends phasing out the waiver completely by 2026.

“Over the years, states have not had a problem finding the resources to fully fund the white land-grant institutions,” the report says. “It’s past time to end their discrimination against Black land-grant institutions.”

[ad_2]

Source link